What is diaphanous and slow, and trails tentacles like skirts or scarves? What is both translucent and luminescent? What undulates and also urticates (stings)? The answer is gelatinous zooplankton—jellyfish, properly termed jellies. Being invertebrates, they lack a backbone: fish they are not. Swimming all summer long in Maryland’s Chester River, we kids loved to detest the common stinging sea nettle (Chrysaora quinquecirrha) or the common moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita).

The stinging jellies are in the phylum Cnidaria (nigh-DARE-ee-uh, from Greek knide, nettle), which also includes sea anemones and corals. One species, the lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata), can grow as big as a VW Bug, not counting tentacles that reach out 60 to 120 feet. Other species could crowd on the head of a pin. Some Cnidaria do not sting, but some, such as the “sea wasp” (Chironex Fleckeri), a pale blue, virtually transparent creature in the “box jelly” (Cubozoa) class, has a bell as big as a bucket, long tentacles, and a sting that kills a swimmer tangled in its tentacles within three minutes. But most jellies are harmless to humans. They are sea predators that sting to stun small prey.

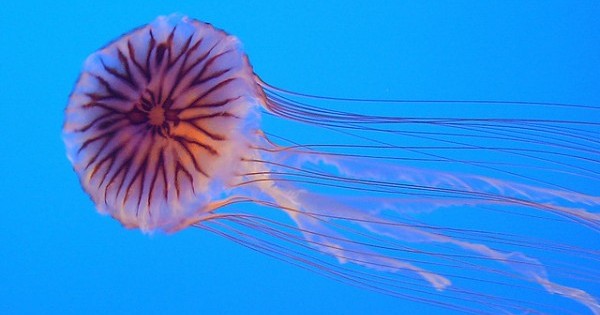

The gelatinous zooplankton we call jellyfish are in their “medusa” stage—the familiar dome-shaped top (the bell) with tentacles hanging down, reminiscent, it may be, of the mythical Medusa who has snakes for hair. They are either male or female and reproduce sexually: in most species, males and females shed sperm and eggs into the water. The fertilized egg grows into a larva that settles on the bottom and attaches to a rock or oyster shell and becomes a polyp. When conditions are right, the polyp begins forming lateral grooves like a stack of dominoes and there begins a process of asexual reproduction in which each domino breaks off and grows into an individual jelly in the medusa stage.

They swim by pulsing their bells, but swimming is not their strong suit; they are largely pelagic, floating with currents and tides. They have a net of nerves but no brain. Their mouth is at the bottom center of the bell, and this opening also serves as anus. This disgusting-to-us digestive system works for them, with the disadvantage that only one batch of food can be processed at a time.

Upon occasion, massive aggregations of jellyfish—known as jellyfish blooms—put a pox on human endeavors. Jellyfish sting swimmers. They plague resort beaches the way bed bugs plague resort hotels. Jellyfish can interfere with fishing, clogging nets and stinging fishermen drawing up their catch. Power plants, nuclear and otherwise, often intake seawater for cooling and jellyfish blooms force shutdowns. They interfere with aquaculture, killing fish in their pens.

It’s possible that jellyfish blooms are burgeoning in our warming, plastic-infused, over-fished, polluted oceans. (Some disagree, since blooms are cyclical in any case. Data is very incomplete.) It’s also possible that the warming of coastal waters by power plants and development stimulate blooms of certain species. Fish and the jellies live in a complex interrelationship; overfishing likely contributes to blooms.

Jellyfish sometimes bloom as an invasive species, imported, and thus relieved of their home predators. This happens when ships take on ballast water in one part of the world and dump it in a distant port.

Jellyfish are not evil, but an increase in the number of blooms suggests an ocean out of whack. On the positive side, gelatinous zooplankton help mix ocean layers. More than a hundred species of fish feed on them, as do sea birds and sea turtles. Jellyfish make shelter for species such as crabs that are unaffected by their venom. Dolphins play with them.

And we humans eat them. Just Google jellyfish recipes.