Texas executed Billy Joe Wardlow on Wednesday evening at Huntsville State Penitentiary for the 1993 murder of an 82-year-old man. Wardlow was injected with a lethal dose of pentobarbital and pronounced dead at 6:52 p.m. He was the 570th person Texas has executed since the Supreme Court reinstituted the death penalty in 1976. Since that time, the state has put to death almost four of every 10 people executed as punishment in the United States. Texas is the extreme example of how unfair the nation’s capital-punishment system is. Wardlow’s case makes that unfairness plain. Based on his remarkable growth as a human being while living for more than two decades on death row, among other legal reasons, it is confounding that the Supreme Court turned down his lawyer’s petition for a stay of execution shortly before it took place. The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles had already rejected, 6-1, his plea for a less barbaric penalty than death.

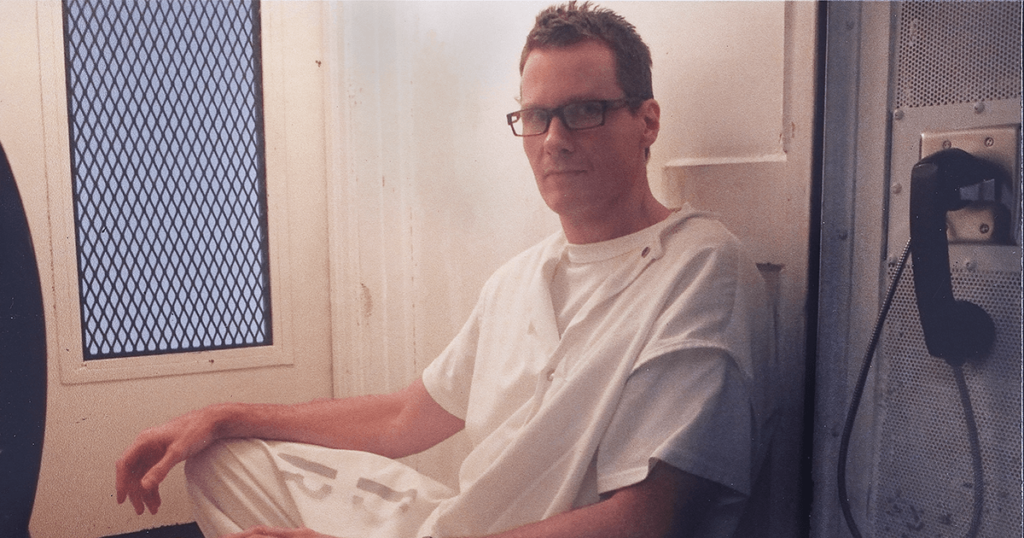

Twenty-five years ago, Wardlow arrived at the Huntsville prison as a tall, skinny, frightened 20-year-old, with what another inmate called a “nervous stare.” He had been sentenced to death for shooting and killing a man named Carl Cole in Cason, Texas, while stealing Cole’s truck. Although he hadn’t expected to be sentenced to death, once he was, he thought he would be executed right away. Instead, he spent a generation on death row and grew up there, as I wrote about in the Scholar this past winter. He became a good and responsible man.

Texas’s execution of him was based on a prediction by a state jury that he would be dangerous to society in the future and needed to be executed to protect even other prisoners from him. When Wardlow killed Cole, he was 18. His still-forming brain allowed his emotional impulses to overwhelm his rational self-control, a brief in the case suggested, and meant that his character was also in a formative state, making it impossible to predict who he would become. He evolved in a quarter of a century from an immature reckless hothead to a mature thoughtful peacemaker.

Wardlow’s good character at the age of 45, when Texas executed him, proved that the jury’s prediction of his future dangerousness was wrong. In 2005, the Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for anyone under 18 when they committed their crime, because they were not mature and thus less blameworthy. Today, neuroscience and neuropsychology make clear that the ban should be extended to include anyone under 21 when they commit murder, including 44 people in that category who remain on death row in Texas.

When I met with Wardlow on death row a year ago, the weight of his concentration during our conversation took me by surprise. The experience reminded me of conversations I had had with a friend who became a Trappist monk. I didn’t share that comparison with Wardlow until two months ago, after he wrote me a letter in which he made an analogy between the confinement of a prisoner and the cloistering of a monk. “Life doesn’t have to be about the sensory world beyond these walls,” he said. “Think of the monks that spend their lives in a temple and never leave.”

I told him about my friend and other monks I had met, whose lives were governed by their faith. They would have known exactly what Wardlow meant. In the ritual of prayer called the Liturgy of Order, starting before dawn and ending at night, they carried out what they regarded as the work of God. I wrote to Wardlow, “Their belief, their conviction, was that prayer—their prayer—could make the world a better place.” I asked, “What is the equivalent for you, as an organizing principle?”

He answered, “I want to cause no more harm. I want to erase the pain I’ve inflicted on others. I want to be someone those I respect would be proud of. I want to be useful to those I love. I want to be someone others look up to and respect, like my dad or Mandy”—one of his lawyers. “I want to wipe away the taint of my past. I realize this isn’t an eloquent answer, but it is about as close as I can come to explaining what drives me to keep going.”

I had planned to see him again in March, but the pandemic kept me from traveling to Texas. Instead, we wrote three long letters to each other between April and June, and I got a significant clue about the answer to the most interesting question framed by Wardlow’s personal development on death row, and what the law should have seen as rehabilitation. How did a 20-year-old hothead grow into a 45-year-old peacemaker while largely in solitary confinement for 25 years?

Wardlow used extensive correspondence, with many people, sometimes for many years, to figure himself out while trying to be helpful to them, and to find a path to the sense of responsibility that made him a prized member of his death-row community. He was proud that the Jung Typology Test, used to determine personality type, identified him as INFJ (Introvert, Intuitive, Feeling, Judging)—creative, gentle, and caring. In prison, he found purpose as a handyman, fixing other inmates’ radios, typewriters, and various essentials, and even more so as their counselor and friend.

One of his death-row friends wrote to me last summer, “See, Billy has this straight forward way of talking to me and everyone,” especially when the conversation was about emotional pain. Wardlow explained to me: “With my experiences I can often relate to traumatic events or loss. Being empathetic can bridge the gap where no words can.” He saw himself as “a nobody from nowhere,” who “let myself grow when the opportunity arose,” by using his imagination. That imagination let him live vicariously through the adventures of some of his correspondents, skiing in the French Alps and going on safari in Africa, and, more important, helped him understand what it must be like to walk in the shoes of other inmates.

Listening to the anguish of others helped him face and manage his own. Not long before his execution, a member of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles asked what the board should know about him when considering his plea for a sentence other than death. As he recounted to me in June, “I told the Board member today that she couldn’t understand what it’s like unless she accidentally killed someone and had to live with the knowledge and guilt that your actions caused unimaginable pain to others.”

Wardlow worked until the end of his life to demonstrate that, although when he was 18 he had killed a man, he was not a killer. That effort helps explain why the decisions of the Supreme Court and the Board of Pardons and Paroles were so unjust—and why, without condoning what he did, many people forgave him for his terrible crime and even came to love him.

Please find the cover story on Billy Joe Wardlow here.