True, it might have been something he ate or drank, or some adverse effect of the pills he’d taken in the bathroom. Though arguably Ira had not been acting like himself all evening. Arguably he had not been acting, in any meaningful sense, at all.

Was this a problem? According to Vanessa, a reluctant authority on the subject, he’d been acting too much like himself for far too long. In light of which his unexpected absence from the table—his sudden, weirdly frictionless descent, sometime between 9:15 and 9:30, to the floor below—might be seen as a welcome if not overdue development: a case of existential addition by subtraction, if you will.

If you will! Ira thought, wincing. Why was he asking permission? From whom, Siri? Alexa? For what? At some point he’d lost purchase not just on the seat of his ladder-back chair but on other, more or less foundational postures as well, like where he was, who he was, even if he was. Now he lay below the table, his head planted on the floor like a headstone. His mouth was parched. His nose was running. His ears roared like thruways. His limbs were flung out around him in boneless heaps, like so much discarded laundry. His eyes were like one of those telescopes you put a quarter in to look at the landscape, only there was no quarter, and not much of a landscape either. For all he knew, there wasn’t a telescope.

“He keeps saying it was a joke. He wasn’t seriously implying.”

“She’s pressing charges?”

“Not in any legal sense. But you know how it is once HR gets involved. There are all these protocols and procedures.”

“Poor Ira.”

“Poor Ira?”

Poor Ira, as it happened, was still lying under the table at that moment, staring up blankly, as if trying to recall the license plate of a truck that had hit him. Above him, people went on chatting blithely as usual, conducting their vertical business. Below him, the planet wobbled precariously on its axis in sodden jerks, like a rotisserie chicken. Branches tittered against the windows. Stars tumbled from the sky. The candles threw ludicrously elongated shadows over the carpet. The walls wheezed and juddered like the lungs of an accordion. The massive oak legs of the table, the baroque wrought-iron chandelier, the squat complacent Buddha of the wood stove … all had turned blobby and labile in the candlelight, as if in deference to some tyrannical law of moronic motion from which Ira alone was exempt. Ira alone didn’t move. Or rather couldn’t move. Or rather didn’t want to move. Why should he move? There were so few places to go, and so much time and space to go there in. No, he thought, better to remain where he was, gazing up into the joisted undersides of Don and Mira’s farmhouse table, and the crotches and lower extremities of his wife and friends, until the next move went ahead and announced itself.

So far, it had to be said, the next move was pretty reticent. Pretty mum. But then maybe the next move, knowing it was the next move, had the discipline, the inner security, to bide its time until the last move got bored and went home.

Either that or the next move was clinically depressed. That was possible too.

“What about a more aggressive approach,” Don said. “Let me write a letter to the board. A few pointedly threatening remarks on the right legal stationery can work wonders.”

“Yeah,” Vanessa said, “let’s double down on the toxic masculinity. There’s a strategy.”

“What’s the alternative? Hiding and playing dead while other people decide your fate?”

“You’re other people too,” Vanessa pointed out, with her usual cryptic, maddening logic.

“Everyone’s another person,” Mira chimed agreeably. An assistant principal at the local middle school, she was an old hand at conflict resolution. “Though I’m not sure how much help we’ll be able to provide from Morocco.”

“Morocco.” Vanessa repeated the word like a solemn liturgy, her voice rising on the r, bumping across the formidable c’s, and then falling, depleted, onto the final o. “I forgot you were going.”

“We’re eager to see the petroglyphs,” Don said. “They have these amazing circular patterns down in Oukaïmeden. No one knows what they signify.”

“Probably shields,” Mira said.

“No one knows,” Don insisted. Nearby, curled on the area rug, Gulliver, Don and Mira’s massive, ponderous Bernese, was licking his asshole with savage, dogged tenacity, like someone digging for buried treasure. “By the way, I’d like to point out Vanessa hasn’t touched her cookie, which I baked with the sweat of my own hands, thank you very much.”

“Leave Vanessa alone. She’s an adult. Maybe she’s cutting carbs.”

“Nonsense. She just ate half a baguette.”

“It wasn’t half,” Vanessa said, picking up a cookie and nibbling at it suspiciously. “How strong are these puppies anyway? They taste pretty potent.”

“It all depends,” Don said. “It’s a function of personal tolerance, really.”

“Yeah,” Vanessa said. “That’s what I’m afraid of.”

There were other, less personal reasons to be intolerant of Don’s cookies, like their taste and texture for instance, which in Ira’s opinion were historically hit or miss. But then Don was a late arrival to the edible drug trade. He was still mastering the nuances. A member of the state bar, the Episcopal Church, the town planning commission, and the advisory board of the local library, Don had smoked, by his own count, all of three joints in his life. Only after his prostate procedure had he been introduced to the pleasures of medical marijuana, and fell into their plush embrace, as Don liked to say, headfirst. That was Don’s way: all in. If you could divide the world into those who went around intensely engaging with things—who went off and climbed mountains for no reason, who built houses for the homeless, organized fundraisers for the fundless, who volunteered to coach Little League for other people’s children, who raised leafy green vegetables from stony, recalcitrant soil, who reared small hoofed animals in a humane organic manner and butchered and cooked them for friends—and those who preferred to sit back and contemplate dividing the world into binary oppositions instead, there was no question to which group Don belonged. The other group, Ira thought. The better group. To watch Don manipulate a kayak, or tinker with the workings of an antique Italian motorcycle, or macerate mint he’d grown himself at a kitchen counter he’d built himself while he slow-cooked a lamb he’d killed himself, was to witness a master class in amiable, can-do competence. So what were edibles to Don? A piece of cake. One more bumper crop in the garden. He already had the raised beds, the grow lights, the thorough, scholarly grasp of soil management. A few books from the library, a few YouTube videos and downloaded podcasts were all he required. Now he tooled around his cathedral-domed kitchen at night in his baggy lab coat–like apron, churning out trays of brownies and cookies and benign-looking lemon and maple bars, all of them laced with substances that were nowhere near as controlled as they arguably should have been.

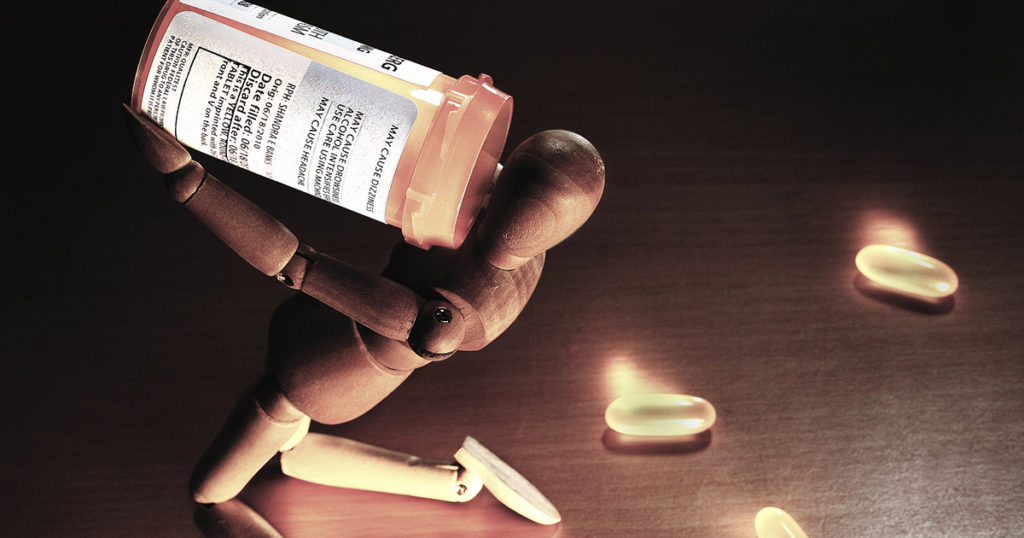

That not all of Don’s edibles were entirely edible did not diminish Ira’s appreciation of the passion and generosity of spirit that went into them. In any case, he refused to complain. It had been a long time since he and Vanessa had been invited out to dinner, and under the circumstances at least one of them, he thought, should make a social effort, should graciously accept what was offered and try to enjoy it for a change. Which he had. Over the course of the evening he’d graciously accepted and enjoyed any number of things: a couple of tumblers of Don’s excellent rye, half a bottle of Don’s excellent wine, three shot glasses of Don’s excellent homemade limoncello, a few alternating slugs of Don’s DayQuil and NyQuil, two or rather three of Don’s Lorazepams, which he hadn’t technically been offered but had found in the bathroom and gone ahead and accepted anyway, along with an indeterminate number of Don’s rather dry, foul-tasting cookies. And if in the wake of all this gracious receptivity he was now experiencing a little minor vertigo, a little woolly wooziness when it came to performing certain basic functions of movement, cognition, and speech, so be it. Better to err on the side of politeness for a change, the side of graciousness for a change, the side of inoffensiveness for a change, even if it killed him. Which for all he knew it had.

“He’s totally weaponized the kitchen,” he heard Mira saying. “Between the funnels and the scales and the hand grinders on the counter, I can hardly squeeze in to make a pot of tea.”

“People don’t realize,” Don said. “They think you just stroll into the kitchen and throw a bunch of stuff together willy-nilly. There’s trial and error involved.”

“It’s not the trial people object to, love.”

“Metabolic calculations. Gut chemistry. Body fat solubility. Fatigue level.”

“Mmm,” Vanessa said vaguely.

“Hydration. Mental outlook. Set and setting.”

“Mmm,” Vanessa said again, her own fatigue level rising, or falling, or anyway getting worse. Not that it had been all that buoyant to start with. From her posture (stiff) as she’d applied her foundation that evening, her gaze (absent) as she took in the shirt he proposed to wear, her dialogue (minimal) on the drive over, her grip (murderous) on the neck of the Prosecco bottle as they’d stood shivering at the door, Vanessa appeared to be having some fronting issues of her own. Ira gazed up from below at the shadowed planes of his wife’s face: the brilliant green eyes, the downy corona on her cheeks, the bow-shaped mouth, the placid and capacious brow whose inmost chambers increasingly required, where Ira was concerned, special permission to enter. It was a survivor’s face, he thought, even now, protean and formidable, still every bit as quick-witted and sensible and lovingly chiseled as the face he’d fallen in love with in the second term of the Clinton administration, and as they’d stood on Don and Mira’s striped, eco-friendly doormat that evening, listening to the wind chimes bang in the breeze like someone sounding an alarm, he was desperate to say something commensurate with his feelings, something that would surprise that face, or relax it, or console it, some tender, intimate message that would make that face feel better, if not about him—that train, it seemed, had left the station—then about Vanessa herself. Regrettably, however, pretty much everything that came to mind was in fact about him.

“The point is,” Don said, “it’s not kid stuff. Not just fun and games.”

“I’m sure you’re right, lovey.”

“I mean people have no idea what’s entailed.”

“I think they sort of get the gist though.” Mira patted Don’s thigh to assure him she was not being bitchy or hostile, merely cognizant of the hour, and the dishes to be washed, and the dog to be walked, and the first and second laws of thermodynamics predicting the imminent heat-death of them all. Or maybe she was being hostile. “Don gets intense about this stuff, don’t you, lovey? And here I thought the whole point of a hobby was to relax and have fun.”

“I’m fun,” Don said. “Ask anyone. I lead the league in fun.”

Alas this rather plaintive assertion was not, strictly speaking, true. Ever since his prostate procedure, Don’s happy-warrior gloss had calcified; he’d begun to take on the stoic, besieged look of a lone sentinel in a turret, scanning the horizon for Goths. His lustrous silver hair had dulled. His neck was puckered and stringy, the capillaries in his cheeks inky and dark like Rorschach blots. From Ira’s vantage below the table, the picture did not improve. Don’s legs were gaunt, his knees bulged like skulls, and between the languid fold of his calves and the wilted droop of his socks, two milk-white ankles lay bared, gleaming and smooth, immaculate as porcelain. Ira shuddered at the sight of them. He remembered Don’s legs on the tennis court, furry and feral like an animal’s. Where had the hairs gone? Was Mother Nature that eager to be done with them? Yet another question for Siri and Alexa, Ira supposed. The poor women: it must have been a lonely life, high up in the cloud, floating everywhere and nowhere like a ghost.

But maybe that was their preference. Some people had renunciatory instincts. They longed for remoteness, apartness, a life unencumbered. They said, No, in thunder! to the usual bullshit, and soared free.

Unfortunately Ira wasn’t one of those people. He liked the usual bullshit; he was good at the usual bullshit. It was the other, more austere and numinous stuff that was hard. Like that silent meditation retreat Don and Mira had dragged him to down in the Berkshires, five days of intensive spiritual contemplation in placid pastoral surroundings, an interlude so charged with numinous austerity that nothing short of a court-mandated order (by no means an impossibility of course, the way things were going) would ever persuade him to repeat it. Okay, maybe he was superficial. Maybe he’d be a deeper, more well-adjusted person if he was more conscious of his breathing, and the inner lives of bees and wasps; if he learned to separate the wheat of his being from the chaff of his thoughts, to bow when he entered and left a room, to subject every withered little raisin to 30 mindful, deliberate chews. But fuck it. If a man was not his thoughts (he thought), what was he? And who had time to find out? The world was a busy place, an integrated, data-based system in which everyone had to step up and play their part. Even if that part felt criminally small. Even if that part felt woefully underwritten. Even if that part, through no legally actionable fault of your own, landed you in hot water with your fellow part-players.

At least in hot water you knew you were alive, Ira thought. At least in hot water your naked self was exposed in all its unsightly bulges and decavities and, for a while anyway, scoured clean.

Still, arguably there were times when a retreat was called for. When a retreat was the best way forward. When the need for truth became urgent, and you had to shut off the noise and distractions. Log out, close down, cleanse the mind’s screen of streaks and smears and ghostly, self-punishing reflections, then sound the gong and lie still.

“Who wants another espresso?” Mira said. “I’ll go warm up the machine.”

“Not for me,” Vanessa said. “I’m actually starting to feel that cookie a little.”

“Really? You only ate two bites.”

“Yeah well, I’ve always been a cheap date.”

“I’m the opposite,” Mira said. “Aren’t I, lovey? I require a lot of effort. It’s one of the things you adore about me.”

“One of many,” Don sang-songed pleasantly. Maybe he was feeling the cookie a little too. “What do you think, Gulliver? Is Mommy man’s best friend or what?”

Gulliver lay on the area rug a few feet away, snoring faintly, his mounded ribcage rising and subsiding, his limbs tremoring from the exertions of some demanding dream. A noble creature, Ira thought. He looked like one of those kohl-eyed Egyptian deities who ushered you through the underworld and presided over your mummification. Why didn’t they have a dog, he wondered? The children had wanted one, but they’d held off for some reason, and now the children were gone and it was only the two of them and their various rages and disappointments and technological devices for company. Dogs were comfortable on the floor. Dogs knew how to lie around, boneless and half-sensate, neither here nor there. Dogs seemed to intuit, deep in their animal bones, the fundamentals of existence, the simple truths that eluded all those lugubrious philosophers he’d read back in college, that Siri and Alexa, for all their algorithmic data, were too ethereal and disembodied to grasp. Dogs just knew. The world is what it is; the rest is commentary. Oh, if only he had a dog, Ira thought. If only he were a dog! Everything would be so much truer and simpler.

But of course he wasn’t a dog. That was a simple truth too. Which meant it did not come altogether naturally to Ira to spend this much time on the floor, with nothing to do but listen to the dog whimper and snore, and the wind knock against the windows, and his breath whistle down the chute of his philtrum, and his heart pound sullenly against his chest, like an opiated timpanist who’d lost his score. Meanwhile, the tinkling playlist of human discourse streamed on blandly overhead, like an uninspired cover band on the deck of some passing cruise ship.

Where the ship was going exactly, and why Ira wasn’t on it, and how and when he’d fallen—or jumped?—overboard … all these were mysteries of a kind no one seemed eager to investigate.

Ira himself had no clue. Vaguely he recalled rummaging through Don and Mira’s medicine chest, looking for contact solution for his raw, itching eyes. All he’d found was a bottle of aspirin, which he’d taken. And the bottles of NyQuil and DayQuil, which he’d also taken. And then the happy accident of the anxiety meds, which he’d also taken, washing them down with a glass of water from Don and Mira’s private well. The taste of the water was a shock: so cold and astringent, with so few sediments or impurities, he could hardly believe it was real. Was anything? The face he confronted in the mirror—a droopy-eyed, wild-haired clown with the pale glazed complexion of ice run over by a Zamboni—seemed a pretty good argument against it. The sight was so appalling, it required another dose of anxiety meds, just to mitigate all the anxiety his efforts to mitigate his anxiety were causing him.

Then he went back to the table. Or rather lurched back to the table. Or rather steered a wobbly, elliptical path in the direction of the table, finally making it back to his chair before abruptly surrendering it again a few moments later, arriving at last at his ultimate if not final destination: the floor below.

And now here he was. Well, what did he expect? The world’s net had so many holes and so little string—it was a miracle they didn’t all slip right through. That was the real revelation, he thought. You could wander off the grid, plunge down the rabbit hole, fly below the radar, without even trying—without so much as moving apparently—and the incredible part was no one noticed. No one even cared. Why should they? The radar towers were empty. There were no controllers at the console, tracing the flight paths of the species through a headset, charting those stammery little blips of runaway light. Were they all just floating out here, untethered in weightless space, unwatched, unknown, unjudged? Yet another question for Siri and Alexa, those oracular angels, if they ever condescended to come down to earth and take a little pity on him. God knows he could use some.

Meanwhile, overhead, Don, a fiend for detail and due diligence, was still ticking off the nuances of Indica v Sativa.

You had to admire the man’s energy, Ira thought. Even now, his fingers were at work, braiding the fringes of his leonine Old Testament beard—the white streaked with red like a burning bush—as he unscrolled his little creation tale of innocence and experience. As stories go, it was less than riveting stuff. The structure was top-heavy, the tempo glacial, with long, turgidly Levitical lists regarding weights and measures and quotients and gradients, and all the while Mira was squirming around in her chair and Vanessa murmuring “Mmm” in that tone of dutiful but distracted brightness that was her default mode when someone, generally a man, generally Ira himself, in fact, launched into a long, needlessly detailed story she would have cheerfully strangled herself not to hear. Not that Don cared. He was having a terrific time laying out the particulars. The organic gluten-free flour he’d milled himself, the eggs plucked from the nests of his own chickens, the clarified butter he’d brewed with the sugar trim, the blackstrap molasses he’d found on the Internet and added at the last minute as a binding agent. You needed a good binding agent, Don explained. Something dense and dark to hold things together. What with everything he’d been through, it was nice to see the man’s powers of industrious research still humming along undiminished.

Nonetheless Ira’s own powers that evening—his double-negative capacity not just to do things, but to resist doing them as well—were nothing to sneeze at either.

“It’s all well and good, I suppose,” Mira was saying. “Except I’ve put on seven pounds.”

“It’s done wonders for your sciatica though,” Don said. “You said so yourself. Plus we sleep like the dead.”

“True. We don’t even dream.”

“The thing is,” Vanessa said, “I hardly remember what it feels like.”

“What what feels like? Sleeping?”

Vanessa paused. If that pause seemed, in tempo and duration, unnaturally long to Ira, it should also be acknowledged that a number of things were beginning to seem unnaturally long to Ira, up to and including his life.

“Anything,” she said.

“Tell you what,” Don said, “we’ll put together a care package for you guys. Take half a dozen cookies home with you. Stick them in the freezer. They’ll keep.”

“I better pass,” sighed Vanessa. “I’m supposed to be in ketosis anyway.”

“You too?”

“My naturopath wants me to eliminate stress agents. Carbs, sugars, caffeine, dairy, one by one down the list. Like a treasure hunt in reverse.”

“Text me her number,” Mira said. “My bowels’ve been irritable for weeks.”

“Isn’t it great that we’re all such good friends,” Don declared, “and can share these intimate details.”

“Look who’s talking. Mr. Gut Chemistry and Liver Absorption himself.”

“What’s this craze for elimination all of a sudden? How much are we supposed to eliminate? Shouldn’t we leave some stuff around for Death to do?”

“Speaking of stress agents,” Mira said, “where’s—”

“Search me,” Vanessa said. “He said something about contact solution.”

“Wasn’t that a while ago?”

“He might have fallen asleep in there. Sometimes I find him sitting on the toilet, lost to the world. It’s kind of his safe space, I think.”

Ira would have liked to protest his innocence—he’d been doing a lot of that lately—but he had a few set-and-setting issues of his own to deal with. Namely the floor under the dining table, which for all its rustic antique charm was nowhere near as user-friendly as it looked. The oak planks, which Don had reclaimed (a nicer word than “stolen”) from a neighbor’s barn, were riddled with fissures, wormholes, and stress cracks. Like all organic matter forced to spend too much time together, they had grown increasingly warped and divided, leaving jagged crevices through which dank air seeped up unimpeded from the basement and whatever orphaned detritus had eluded the tug of Don and Mira’s vacuum cleaner over the years—the dust bunnies, the cracker crumbs, the dead flies, the soot-darkened pennies—found shelter. Did Don and Mira even own a vacuum cleaner? They were famously informal (a nicer word than “cheap”); maybe they got by with a broom. But then they had no way of knowing their guests would be spending so much time down here inspecting the place, Ira supposed, either.

Even worse was the smell—the rank, fusty odors of other people’s feet. If only shoes were not verboten at Don and Mira’s haus! But no, you had to surrender your footwear at the door. You had to cleanse yourself of all earthly contaminants, of mud and rubble and snow, had to get down on your knees in the mudroom like a penitent, prostrate before some unnamed, vaguely mystical eastern God concept whose protocols no one ever undertook to explain. Only then would you be judged suitable for entry. Only then would you be force-marched down the foyer into the kitchen, and have your genitals submitted for vetting by Gulliver’s wet, inquisitive snout; only then would you be handed a glass of blood-dark, beautifully decanted Rioja from some promising start-up vineyard, and presented with an immaculate wheel of cheese circled like the petals of some stinky, sun-bleached flower by a ring of dolmas, or artichoke hearts, or chia seed crackers; only then would you be ushered into the dining room, served a fabulous meal of winter squash gnocchi and sautéed spinach with pancetta and dried cranberries, and asked a series of well-meaning questions over coffees and grappas and the usual Tupperware container of Don’s famously hit-or-miss edibles about your parents and children and whatever you happened to be reading and/or binge-watching and/or freaking out about politically, until the first surreptitious yawns would remind you that as Don and Mira rose early every morning to walk the dog and feed the chickens and meditate in the gazebo or whatever, you should probably retrieve your goddamn shoes and scoot out the door by 10.

Yes, that was the deal. That was the social contract you signed here in the provinces, if you wanted a social life.

Of course, there were worse ways to spend a winter evening up here in the provinces, as Ira could tell you, having spent no few of those worse evenings himself. He knew how stark and unfriendly things up here in the provinces could get. The moon loitering blankly overhead. The roads with their blackened, impenetrable glaze of ice. The pale webs of frost, spectral and intricate, stealing over the windows. And meanwhile, here was this big cozy house on the side of a mountain, ablaze with light. Here was this roaring hearth, this shaggy, amiable dog, this antique table full of art books and quality magazines, Segovian arpeggios trickling like snowflakes from the cathedral ceiling. Who could say no? Not Ira. Oh, maybe he’d resisted a bit at first, had been slow to get with the program, as it were. But now that he and Vanessa were firmly ensconced up here, as Vanessa would say, now that their weekends were devoted to such world historic matters, as Vanessa would say, as hiking and wood-stacking and inspecting their clothes for ticks, now that they had checked out every restaurant within a 50-mile radius and found them, as Vanessa would say, spectacularly wanting, they’d given up and sued for peace. Okay, it wasn’t Paris or Barcelona. It wasn’t San Francisco or New Orleans. It wasn’t even Providence, Rhode Island. But at some point you had to settle down and live where you lived. If you wanted a piece on the game board, you had to play by the rules. And the rules were clear: the rules stated unambiguously that the rewards of any civilization, however vapid and mediocre and prosaic, depended on the repression and containment of its discontents. So why complain? It was a waste of everyone’s time. No, when it came to complaint, everyone had a constitutional right to remain silent. Or, as Vanessa would say, to shut the fuck up …

“Of course,” Don was saying. “It’s the ideal solution. Just what the doctor ordered.”

“Can they still get tickets, do you think?”

“Why not? Let’s rev up the search engines and take a look.”

“Forget the doctors,” Vanessa said. “It’s the lawyers I’m worried about.”

“I’m a lawyer too,” Don said. “That’s why you can trust me when I say, a principled retreat is often the best strategy. Let the thing die down on its own.”

“Look, it’s incredibly sweet of you—”

“I’m not being sweet. Tell her, Mira. I don’t do sweet. I do shrewd and pragmatic.”

“I’m afraid you do do sweet, lovey. The sweet thing is you don’t even know it.”

“Honestly, there’s nothing I’d like more,” Vanessa said. “But this is kind of a weird time for us.”

“All times are weird. It’s one of those sad little Zen truths that bears repeating.”

“Except by weird in this case I mean really fucked up and bad.”

“Listen, if you’ve got cash-flow problems, we’re happy to help out. It’s super cheap over there anyway. Wait’ll you see this cool hotel we booked in Fez. Eighty bucks a night. Where’s my phone?”

“It’s not the money,” Vanessa said.

“Check out the rugs and pillows. The ornamentation. The fountains in the courtyard.”

“Not just the money, I mean.”

“Listen, everyone knows you guys’ve had a tough year. Boo hoo. We’ve had a rough year too. Tell her, Mira. You wouldn’t believe the shit we’ve dealt with on the cancer front. But you can’t sit around. You have to get back on the camel. Make a move. Take a chance. Like that old saying—change your scenery, change your luck.”

“I’ve literally never heard anyone say that,” Vanessa said.

“We’ll visit the great mosques. We’ll wander the medinas. We’ll check out the ancient tanneries. We’ll schlep up to the Atlas Mountains and eat mahjoun with the Berbers.”

“What’s mahjoun?”

“It’s this incredible stuff they make with dried fruits and spices and clarified butter. Very healthy and healing. It’s full of hash. They say it’s an aphrodisiac too.”

“It’s going to need to be very strong,” Vanessa said.

“What if the Berbers don’t want us there?” Mira said. “They’re supposed to be super xenophobic and fierce.”

“Only when attacked,” Don said. “Like everyone else.”

“Something about cutting people’s tongues out. People crawling naked down the street like dogs.”

“Listen,” Don said, “they’re a proud people. You don’t survive 10,000 years in a hostile climate without a little vigilance. That’s why they build houses underground, you know. For protection. Half the time you don’t even know they’re down there.”

What about the other half, Ira thought dreamily, if the word thought could even be applied to what he was doing at this juncture, and the word Ira even applied to who was doing it. He felt himself drifting along under the table like a jellyfish, borne by invisible tides into uncharted waters under no particular jurisdiction. It was neither a bad feeling nor a good feeling. It was more like no feeling at all.

“I’m a little high,” Vanessa announced abruptly.

“We’re all a little high, I think,” Mira said.

“Yeah well, I’m going home.”

“Is that a good idea?” Mira said. “Maybe we should wait for Ira.”

“I don’t want to wait for Ira.”

“He’s been gone an awfully long time though,” Don said, “hasn’t he?”

“Maybe you should get your keys,” Mira said. “I don’t think Vanessa should be driving herself home right now.”

“You want me to take her? I’m happy to take her. Maybe I should take her. Though wouldn’t it be better to wait for Ira?” Don really was a sweet person, Ira thought; he was lucky to have such a good friend. “Where did he go?”

“You’re not hearing me,” Vanessa said. “I don’t want to wait for Ira. I’ve done that. I’ve waited and waited for Ira, and I don’t want to wait for Ira anymore. Am I making myself clear?”

“Perfectly,” Don said.

“Okay then. Off I go.”

“But what about Ira? Where does that leave Ira?”

This seemed, to Ira at least, a perfectly reasonable line of inquiry (he himself was curious to know), but unless he was mistaken, no one ever bothered to answer it. Apparently, people were tired by that point, tired of questions, tired of answers, or maybe they were just tired of him. In any case, they all pushed back their chairs from the table at once—the legs scraping harshly, peremptorily against the floor—and went trooping down the foyer to the mudroom. Gulliver trotted off to attend them. There was the usual transitional choreography of leave-taking, the promises and disclaimers, the rustle of coats, the squeak of boots, the whoosh of doors pulling open, the thud of doors closing shut. Then things grew quiet for a while. He heard Don and Mira murmuring wearily in the kitchen. Bottles clinking into the recycling bin. Water trickling in the sink. The rumble of the dishwasher doing battle with the smears and streaks they’d left on their plates.

There was a smell of smoke, melted wax. Someone was walking around the table, blowing out the candles.

The house had had enough of the hospitality business, and was calling it a night.

Ira lay there alone. Darkness rose around him like a solvent. He could feel it on his skin, exfoliating the surface, flaking away the crust, a black sea reclaiming a small, recalcitrant island. Well, he thought, let it go. One by one they were all losing their shit anyway. He had lost his job, his salary, his place at the table. Don had lost his prostate; Mira had lost a breast. Vanessa had lost her patience, her tolerance for human failure—or Ira’s human failure anyway. Or maybe the opposite was true; maybe she’d grown so resigned to human failure, so accommodating of human failure that she no longer hoped for or expected anything else. Which would be, Ira thought, the worst loss of all.

Outside, gusts were howling through the yard. Why were the winds of winter so harsh? The trees looked spindly and denuded, their arms out-flung like martyrs; their desiccated fruits were rotting in the snow. He supposed they were seeding the ground in their own way, providing proteins and minerals for the crocuses and dandelions to come. But what a slow, maddening process. And meanwhile, there was all this ugliness to endure.

“Where’s Vanessa? ” he heard someone cry, in a voice he didn’t recognize. “Where’s Vanessa? ”

The dog began to bark. It made a tremendous racket; the very walls trembled. There were footsteps in the hallway, voices calling back and forth. The room filled up with light. The next thing he knew, Don was leaning under the table, his face beaming down wanly like some pallid moon.

“Well look who it is,” Don said. “The invisible man returns.”

Ira smiled shyly. He tried to give Don a casual, insouciant wave to indicate he had the situation under control, there was no need for alarm. But his hands were asleep. All he could manage was a subtle, possibly invisible steepling of the fingers.

“What’s going on, Ira? We thought we’d lost you hours ago. Where’ve you been?”

“Oh you know. Around.”

“Who are you talking to?” Mira called from the staircase. “Who’s down there?”

“It’s Ira.”

“Oh for fuck’s sake. What does he want?”

“How do I know? He’s lying under the dining table like a dead person. What do you want, Ira? What are you doing down there anyway?”

Ira shrugged. “Nothing,” he said. “Or maybe everything. It’s hard to put into words, exactly.”

“You’ll have to speak up. I can’t understand you.” Don’s tone was at once empathetic and mildly disappointed, as if he were talking to one of his Little Leaguers who’d shown up without his glove. “Are you drunk? No offense, but your voice sounds a little garbled.”

“How strange.” Ira’s words did seem weirdly out of synch with his mouth all of a sudden, as if he were being dubbed into an old, none-too-neorealistic Italian movie. “I wonder what’s up with that.”

“Maybe we should take his pulse,” Mira said. “He might be having a stroke.”

“Nonsense. He’s not having a stroke.” On the chance that perhaps he was having a stroke, however, Don crouched low beside him, taking Ira’s wrist in his palm. “Are you having a stroke, Ira? Is that what you’re doing? Do you need to go to the ER?” He stroked the small bones gently, as if they belonged to some wounded bird who’d foolishly mistaken the transient reflections of the picture window for a path to the sky. It was a moving gesture, Ira thought sadly, though hardly an effective method for taking one’s pulse. “If you can’t speak, try blinking your eyes. One for yes, two for no.”

“Where’s Vanessa? ”

“I wish you’d try the blinking thing,” Don said, in his disappointed-coach voice. “I wish you’d give it your best effort.”

“Where’s Vanessa? Where’s Vanessa? Where’s Vanessa? ”

“Something about Vanessa, I think,” Don reported over his shoulder to Mira.

“Now he’s worried about Vanessa.”

“Hey, Vanessa’s gone,” Don said to Ira. “Sorry buddy. Vanessa left a while ago. She had to go home.”

Ira began to cry. In all probability, he had been crying off and on for some time now without being aware of it. Now he was aware of it.

“Better get out the air mattress,” Mira said. “He doesn’t look in any shape to go anywhere.”

Don disappeared for a while. Then he came back lugging the air mattress, plopped it onto the floor with a grunt, and pried open the valve. The roar of the pump was fearsome but encouraging: another under-powered mechanism hollering into a void. Ira watched the limp, wrinkled nylon shell expand like a balloon, its creases smoothing in the act of extending themselves. Gulliver sat up on his braided rug, sniffing the air, waiting for things to assume their proper density and shape.

“All right then.” Don dusted off his hands and rose from the floor, his arm sweeping outward with a flourish. “All yours. Lay on, Macduff.”

Ira frowned. True, the mattress was only a few feet away, but to manage the distance under these or any other circumstances seemed a ludicrous proposition. Nonetheless, if this was how the species kept itself going, by trivial acts of compliance with pointless, fundamentally arbitrary social obligations, why should he not join in? Don was waiting. Mira was waiting. The dog was waiting. Who knows, maybe somewhere even Vanessa herself was waiting, with that same look of retraction, of suspended expectation. Like a parent teaching a kid to walk. The look God himself was said to have directed, after six days of hasty assembly, upon his ambitious but untested new world. A look that gazed on the clumsy operations of free will with a certain loving forbearance. A certain forgiveness. Because if you fell to the ground, so what? There were worse places to find yourself than the ground, Ira thought.

Slowly, a little at a time, he began to inch across the floor on his backside. It was slow, enervating work, and by any objective standard very little progress was made. On the other hand, he wasn’t sure he wanted to make progress. He felt in no hurry to attain the mattress, hoist himself onto its meager padded comforts, and rest. Let everyone else sleep comfortably; at this point, all things being equal, Ira preferred the floor. The floor was the hill he would die on. Whether he was getting himself together down here, or falling completely apart, he didn’t care. Possibly they came to the same thing. The point was, he was on a journey. He was sinking to the bottom of what he was. The road up is the road down, Heraclitus said. Or was it vice versa? The important thing, he thought, was to go on lying here. So that was what he did. He lay there, listening to the wind howl at the windows, and the last stray embers pop in the wood stove, and the dog tick back and forth across the floorboards, looking for signs of life.