Birthright Citizens and Paper Sons

The complicated case of an American-born child of Chinese immigrants

On a fall day in 1870, a Chinese woman with bound feet gave birth to a baby boy named Wong Kim Ark. He entered the world in the back bedroom of 751 Sacramento Street in San Francisco’s Chinatown, above his father’s grocery store. According to the 1870 census, he was an extraordinary rarity—one of only 518 children of Chinese ethnicity to have been born in the United States up until that time. Almost 30 years later, the child’s birth was at the center of a Supreme Court case establishing that everyone born in the United States is a U.S. citizen—what is known as birthright citizenship—under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The justices who ruled that Wong Kim Ark was a U.S. citizen might have been surprised to learn that the concept remains contested over a century later. President Trump has repeatedly threatened to end the “crazy, lunatic” policy of birthright citizenship for the children of undocumented immigrants. Trump rose to political prominence on the baseless claim that Barack Obama was not born in the United States, and during the election campaign questioned the citizenship of Kamala Harris, who was born in this country to legal immigrants. Even in 2021, many Americans are conflicted about whether newly arriving immigrants and their children deserve the full rights of citizenship.

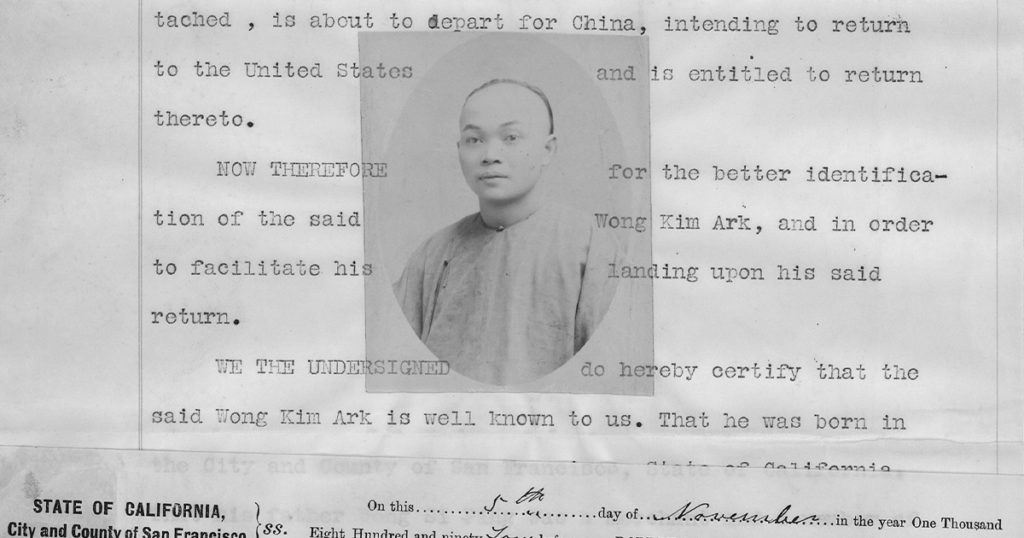

Wong was 24 years old when he began his legal battle. His photo from government archives shows a fresh-faced young man, regarding the camera with a calm confidence. Yet he would endure months in detention and then another three years in legal limbo as his government argued that he was not a citizen entitled to stay in his own country. What motivated Wong to fight so hard for citizenship in a nation whose leaders rejected him?

Government records on Wong and his family stored at national archives in San Francisco and Texas, the states where Wong lived and worked, offer a window into the daily lives of immigrants as well as the inner working of the immigration enforcement system. The government’s oppressive documentation of Chinese immigrants and their families confirmed my worst fears about how racism and xenophobia infused the implementation of the nation’s immigration and citizenship laws. But the archives also led to surprising revelations about Wong and his family—discoveries that cast new light on a man long viewed as the poster child for birthright citizenship, and raised questions about immigration, citizenship, and belonging that still confound the nation today.

Like many Chinese immigrants from Guangdong province in southeastern China, Wong’s parents had come to the land they called “Gold Mountain” to escape poverty and chaos brought on by the 19th-century Opium Wars. But when Wong was about seven years old, the family packed its bags, leaving their home and business behind to resettle in China. They gave no reason for their sudden departure, but it is not hard to guess why. Just a few months before, on the evening of July 24, 1877, a mob of white men had rampaged through San Francisco’s Chinatown. In the words of The New York Times, the men were “resolved to exterminate every Mongolian and wipe out the hated race.” They ripped up slats of the wooden sidewalks to use as battering rams, breaking into Chinese-owned businesses and tipping over coal lamps to set the buildings on fire. When the night was over, four Chinese men lay dead, one shot and then burned to death after the mob torched his home. The San Francisco pogrom came on the heels of a massacre a few years before, when 18 men of Chinese ethnicity had been lynched in Los Angeles’s tiny Chinatown. Likely afraid for their lives, Wong’s parents fled.

Three years later, Wong was back. At 10 years old, his formal education was over. He arrived with an uncle and started working as a dishwasher and cook in a mining camp in the Sierras. He did not return to China for a decade, when necessity forced him back to find a wife. In 1882, Congress embraced anti-Chinese animus by enacting the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first significant barrier to immigration in the United States, and the first to explicitly target a group based on its race and class. As a result, there were few women of Chinese descent in the United States available to marry, and marriage to a white woman was unthinkable, both culturally and legally under California’s anti-miscegenation laws. If Wong wanted a family of his own, his only choice was to go back to China.

But Wong stayed only long enough to marry a girl of 17, one with bound feet like his mother’s, and to conceive a child with her. He returned to Gold Mountain before his son was born, sending home money he earned as a cook in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Wong had become one of millions of first-generation Americans with a foot in both countries—long periods of work in the United States interrupted by short visits with his family in his country of ancestry. In Wong’s case, as in many others, the pattern was perpetuated by discriminatory federal and state laws that excluded him at every turn, forcing him to live in crowded ethnic enclaves and limiting his choice of work and spouse.

Born in the United States, where he would live most of his life, did Wong feel American? In a photo taken in his mid-20s, Wong’s hair is braided in the traditional Chinese queue, and he is wearing a high-necked mandarin tunic rather than a Western shirt and jacket. He insisted on conducting his immigration interviews in Chinese, even though, as one interpreter noted, “This man speaks English fluently.” Culturally, Wong may have identified more closely with China than the United States, at least as a young man. But legally he knew that his birth on U.S. soil had made him a citizen, as he repeatedly stated on the forms he was required to fill out when entering and leaving the country.

His government disagreed. Wong’s return from a nine-month trip to China in August 1895 coincided with the federal government’s conclusion that citizenship by “mere accident of birth” created an unacceptable loophole in the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Fourteenth Amendment provides, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The caveat “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” was intended to exclude only the children of diplomats, the children of enemy invaders, and Native Americans, all of whom owed allegiance to a separate sovereign and were not compelled to follow many federal and state laws. (Today, the children of Native Americans have U.S. citizenship at birth under a federal statute.) But the government wanted to stretch that language beyond those narrow exceptions, arguing without any basis that a child born in the United States to noncitizen parents owed allegiance to a foreign country, and therefore was not a birthright citizen.

Employing this logic, the government denied that Wong was a citizen by virtue of his birth and refused to allow him back into his country. He was forced to spend the next four months under lock and key on a steamship in San Francisco Bay, and then another three years out on bail while he fought the government all the way up to the highest court in the land.

Did Wong expect to win his case? The United States Supreme Court had an abysmal track record when it came to laws discriminating against the Chinese, claiming in an 1889 case that they were needed to protect the nation against an “Oriental invasion” that posed a “menace to our civilization.” But Wong had one thing going for him. At stake was the future of birthright citizenship not only for those of Chinese ancestry, but for all children of noncitizens. As Wong and his lawyer well knew, his best chance was to tie his claim to citizenship to that of hundreds of thousands of children of white immigrants, ensuring that they would stand or fall together.

And that made all the difference. In 1898, the Supreme Court issued its decision in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, ruling 6-2 in Wong’s favor. Not only was he declared a citizen entitled to remain in the United States for the rest of his life, but he had also won that right for every child born on U.S. soil, regardless of race, color, or ancestry.

Most accounts of Wong Kim Ark and his famous battle for birthright citizenship end with his resounding Supreme Court victory. But Wong’s story is far messier than this textbook happy ending suggests.

For starters, the government proved itself a poor loser. Shortly after the decision, federal officials declared that the “Chinese are an undesirable addition to our society,” and so “every presumption, every technicality … should be held against their admission, and their testimony should have little or no weight when standing alone.” Because no witness of Chinese ancestry could be trusted, the thinking went, anyone claiming birthright citizenship had to produce at least two white witnesses attesting to that fact—a high obstacle considering that Chinese immigrants were forced by discriminatory laws and practices to live in enclaves separated from most whites.

Even Wong was required to prove and re-prove his citizenship, as I discovered after searching archives in Texas, where Wong moved after he won his Supreme Court case. Buried in a crumbling stack of paper files was a previously unknown legal chapter in his long battle for citizenship. In October 1901, immigration officials in El Paso, Texas, jailed Wong again, placing him at risk of deportation because these local officials did not believe he was an American. It took nearly four months before they agreed that Wong was a citizen who had a right to remain in the United States.

For Wong’s children, matters were even worse. On October 28, 1910, his eldest son reached San Francisco Bay from China. Like most arriving immigrants from Asia, he was immediately detained on Angel Island. The detention center had opened its doors only a few months before, and the press had quickly dubbed it the “Ellis Island of the West.” But the two immigration facilities were nothing alike. Ellis Island was a processing center for European immigrants, most of whom were allowed to enter and, if they chose, eventually become American citizens. Angel Island served as a detention center for Asian immigrants, many of whom would be turned away under immigration law and were barred by law from naturalizing. Ellis Island welcomed future Americans; Angel Island excluded unwanted aliens.

If the young man could prove he was Wong’s son, then he was automatically a U.S. citizen entitled to enter the country. But immigration officials were deeply skeptical, questioning father and son for days in cramped interrogation rooms. On Christmas Eve, 1910, a three-member commission issued their unanimous verdict: The evidence “shows conclusively that the applicant’s claims are fraudulent,” they declared, because “material” differences between Wong Kim Ark and the boy’s testimony proved that they were not actually father and son. Wong’s son was deported to China on January 9, 1911, never to return.

For many years after, Wong’s other children made no effort to enter the United States. Perhaps their spirit had been broken by their elder brother’s detention and deportation, and by the hostility of the immigration inspectors. Or perhaps Wong was unwilling to put himself and his children through that process again.

But then 13 years later, in 1924, Wong’s third son, Wong Yook Sue, sailed across the Pacific Ocean in the hope of joining his father in the United States. At first, he had no better luck than his older brother. As before, both Wong and his son were interrogated at length. As before, immigration officials denied Yook Sue’s admission to the United States.

But Yook Sue fought back, choosing to appeal rather than to be deported on the next steamship to China. He got lucky. The decision was reversed and Yook Sue entered the United States as a U.S. citizen. Heartened by this success, Wong’s second son came a year later and was admitted to the United States in March 1925. His youngest child was last to be admitted as a U.S. citizen the following year, but only after spending three weeks in detention on Angel Island. He was a boy of 11, standing only four foot two, who had traveled all the way from China by himself to live with a father he had never met. Wong must have felt enormously relieved—the family’s citizenship battles were finally over.

Yet the government archives had more secrets to reveal about Wong Kim Ark and his family. The immigration files of three of Wong’s sons had long been publicly available, but the files of Yook Sue had gone missing. Then in March 2019, an archivist sent me an email studded with exclamation points—a rare display of emotion from a man who works with century-old documents in hushed rooms. He had located the lost file in another agency’s records.

I was expecting Yook Sue’s record to resemble those of his brothers, filled with dates of steamship arrivals and transcripts of probing interviews by skeptical immigration officials. To my surprise, the first page of this file was dated October 18, 1960, when a man named Ernest J. Wong, a cook at the Drake Hotel in San Francisco’s Union Square, submitted an application to become a permanent resident of the United States. I was confused. What could Ernest Wong have to do with Wong Kim Ark or his son, Yook Sue?

The pages to come made the connection clear. In an affidavit accompanying his application for a green card, Ernest Wong wrote, “I last entered the United States claiming to be WONG YOOK SUE, the citizen son of WONG KIM ARK,” but “I now admit that I am a citizen of China and that I have never been a citizen of the United States. … I am not related to my immigration father, WONG KIM ARK, in any way.”

It seemed that Wong Kim Ark was the father of a so-called “paper son”—the term for Chinese immigrants who fraudulently claim a blood relationship with a U.S. citizen in order to gain admission to the United States. Wong Kim Ark and Ernest Wong had conspired to persuade immigration officials that Ernest was Wong’s son, enabling the young man to enter the United States in an era when almost all Chinese were barred.

Wong and his “son” were not alone in manipulating the system. After the Chinese Exclusion Act took effect, Chinese immigrants frequently made false claims of citizenship. Forging paperwork was easier than trying to convince immigration officials at Angel Island that the new arrival was actually a merchant, who could legally enter, rather than a laborer, who could not. Between 1894 and 1940, 97,143 people of Chinese descent entered the United States claiming to be citizens—nearly half of the total number admitted from China. Historian Erika Lee has concluded that a “large majority of these cases were likely fraudulent.”

Ernest Wong had come forward to confess his fraud as part of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Chinese Confession Program, which operated from 1957 until about 1965. The program arose from Cold War fears that Communist China would use its “paper sons” in the United States to infiltrate the government and undermine democracy. The federal government encouraged the Chinese living in the United States to come clean about their fraudulent claims of citizenship, typically in return for permission to remain in the country as green card holders under their real name, and eventually qualify for legitimate citizenship. For the confessors, it was a chance to wipe the slate clean, to give their families a fresh start in the United States without the convoluted layers of fake documents and lies to weigh them down. For the government, it was an opportunity to root out Communist influences. Men like Ernest Wong were routinely approved for permanent residence, but left-leaning labor leaders were often deported.

The Chinese Confession Program required those seeking to remain in the United States to reveal the names of family members and friends who had also entered the country on false pretenses. Ernest Wong had been flagged by another confessor in an unrelated case, and must have felt he had no choice but to admit that his real father had paid for him to pretend to be Wong Kim Ark’s son. In his one-page typed confession, he took pains to note, “I believe that WONG KIM ARK was actually born in the United States as he claimed,” and also that “the third son, YOOK JIM, is a true son of WONG KIM ARK.”

By the time Ernest Wong confessed, Wong Kim Ark had passed away. We cannot know what Wong would have said in his own defense. But others have explained that the Chinese saw no reason to obey racist laws and policies that barred the Chinese—and only the Chinese—from entering the United States and naturalizing. Ironically, immigration officials’ obsessive documentation of the Chinese enabled those willing to pay for forged papers and expert “coaching” in the immigration process to come to the United States under false claims of citizenship, even as these same practices often barred legitimate citizens such as Wong and his eldest son. One Chinese immigrant explained, “If we told the truth, it didn’t work. And so we had to take the crooked path.”

From the perspective of a century later, the morality of paper sons and their citizen-fathers is complicated—just as complicated as the morality of unauthorized immigration today. Are paper sons and their fathers criminals, or are they the victims of a racist and inhumane system? Did they help or harm the United States? Does the United States regret the presence of a group of immigrants who mined the gold and built the transcontinental railroad at extraordinary speed and under harsh conditions? Or those, like Wong and his children, who took jobs that white Americans refused to do, laundering the clothes and cooking the meals to be enjoyed by the “real” citizens? In the words of Stanford professors Gordon H. Chang and Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Chinese immigrants and their children, both legal and illegal, in big ways and small, “helped build America.” One hundred years from now, when future historians scour the archives for records of the immigrants arriving today, they will surely say the same.