I would never have agreed with Robert Lowell’s comment about the “tranquillized Fifties.” Maybe that’s because I grew up in New York City, which always seemed to pulse with unruly energy. Or maybe it’s because I went to a special high school—Hunter College High School for “gifted” girls, where a clear majority of the students were as unruly, as restless and aspirational, as I was. And maybe, too, because I came from an immigrant family (Niçoise, Sicilian, Russian), I never felt like a regular rule-abiding American. And that was a problem in the supposedly placid (though witch-hunting) McCarthyite ’50s.

Most of my friends were like me. I didn’t know anybody who had grandparents without accents. A grandparent, by definition, was a person from the “old country.” Which old country? Any old country, so far as I could see, from which they had traveled—restless and aspirational, but speaking broken English. Some of my friends’ parents even had accents. But that was New York for you. Hardly anybody was a regular American, the kind you saw in the movies.

To be honest, for much of my childhood I didn’t appreciate New York. I didn’t like being Niçoise-Sicilian-Russian. I wanted to look like Doris Day or June Allyson or, more realistically, Margaret O’Brien, and live in a small town with shady streets, porch swings, and lemonade stands. Not in a six-story brick apartment house in Queens, not in a two-bedroom flat with a dinette and a kitchenette and a fire escape blocking one of the windows.

Still, even as I fruitlessly yearned for leafy streets in some strange American place like, for instance, Ohio, I sensed that I was lucky about food. Though my mother never really learned to cook like the Sicilian she was, my mongrel culinary inheritance offered me endless delicacies. Basta (pasta) enfornata—actually lasagna—at my Sicilian aunt’s Brooklyn brownstone, where my uncle nurtured tomatoes and basilico in a small back-yard garden. A whole tray of hors d’oeuvres at my grandparents’ Kew Gardens apartment, including stuffed mushrooms, eggplant caviar, marinated artichokes, and on and on. Even my father, who did most of the serious cooking for my mother and me, could turn out a mean boeuf en daube. And when Russian Easter came around, my (paternal) Russian grandmother proffered pashka and kulich, the traditional pairing of sweet molded cheese and tall round equally sweet bread with which the Orthodox Church celebrates the risen Christ.

I shouldn’t overemphasize food, though, because my Sicilian mother and my Niçoise-Russian father were left-leaning intellectuals, and thus more focused on politics than pasta. In the fall of 1948, I was sent to elementary school sporting a Henry Wallace button on my winter coat—remember Wallace, who ran as a third-party ultraliberal candidate against Truman and Dewey?—and my parents regularly read the now long-defunct lefty paper PM along with The Nation and The New Republic. As we nibbled those transcendent hors d’oeuvres at my grandparents’ table, my mother would enter into heated arguments with my father’s sister—my churchgoing Catholic “maiden aunt”—about Picasso, Braque, and so forth. My mother was pro; my aunt was con. It seemed perfectly reasonable, therefore, that when my parents decided I too was an intellectual, they gave me a subscription to Partisan Review for my 14th birthday.

Being an intellectual, however, was a source of some discomfort. As a freshman at Hunter High, I suffered because I was 12 and everyone else was 13 or 14. I had skipped a few grades in elementary school (not my idea!), so when I got to high school I lied about my age. I said I was 13. When somebody became a close friend, I haltingly told her the truth. Humiliating! We would sit close to each other on the subway, and over the roar of the F train, she—whoever she was—would comfort me, assuring me that I really looked 13, or maybe even 14.

But my age was not an issue when I signed up to work on Argus, the school literary magazine. I had always written poems—when I was very little, my schoolteacher mother put them in a scrapbook that we titled “Poetry Is My Hobby,” for which I won some prize or other. On Argus, I met the first serious poets I was to know. The most glamorous—because they were two whole grades ahead of me—were Diane di Prima and Audre Lorde. They were best friends, and each was charismatic in her own way, Diane with her long red hair and soulful look, Audre with her fierce gaze and intense pride.

To be sure, both displayed the hauteur with which older girls regard younger girls, but they did acknowledge my existence. (Years later, when I ran into Audre at a feminist conference, she addressed me as “Little Sandy,” and years later still, Diane greeted me with big-sisterly affection when we did a poetry reading together.) But I really didn’t know either of them that well. Not long ago I discovered that at Hunter they were members of a secret society called The Branded, where they called up spirits and engaged in other subversive activities that I’m sure I would have adored!

Though they were “branded” and destined to become famously rebellious poets, Diane and Audre weren’t notably different from most of my other classmates at Hunter. For despite its dedication to “gifted girls,” the school was nothing like the high-minded institution for well-born ladies portrayed in Tennyson’s The Princess and satirized in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Princess Ida. Nor was the school anything like the typical ’50s high school (as portrayed in the movies). Yes, I suppose many of us had sweater sets and crinolines, but those were frequently replaced by less conventional outfits, most of them based on black turtlenecks. Hunter was populated by unruly girls and quite a few equally unruly teachers, some of whom were lesbians during a decade when same-sex sex was definitely dangerous.

All of this was facilitated by New York, and particularly by the enticements of Greenwich Village, where Edna Millay had lived her own unruly life and where old-fashioned bohemians and newfangled beatniks hung out in bars, bookstores, and little theaters. By the time I was 14 or 15, my best friend Chris and I were riding the subway to the West Fourth Street stop, or to the Sheridan Square station, ready to tour the town all dressed up in our black turtlenecks and blue jeans along with the hoop earrings and bright yellow slickers that were then the mode.

One Saturday our English teacher, Miss Newton, took us to lunch at the Jumble Shop on Eighth Street—a charming venue that, unbeknownst to us, was a trendy gathering place for lesbians (e.g., Patricia Highsmith) and artists (e.g., Willem de Kooning). Then we went back to her Waverly Place apartment, where she amused us all by costuming Chris in various exotic gowns, a festive moment interrupted when Billie, the transvestite who lived upstairs, dropped in to show us his glittery new spike heels. (I think I was too tall for Miss Newton’s apparel, or maybe I wasn’t the one she wanted to seduce.)

On weekend evenings, with or without various boyfriends, we’d stroll up and down MacDougal Street to the corner where it met Bleecker. There was the famed San Remo Café, really a bar everyone referred to as Remo. We knew literary guys who hung out there in the hope of running into, say, Dylan Thomas (though he was more often at the White Horse, on West 11th Street). Outside Remo, we did regularly encounter the pitiable figure of Maxwell Bodenheim, once a successful poet and accomplished novelist, swaying drunkenly, leaning over a car or vomiting into the street. Chris and I and our boyfriends knew he had had quite a reputation in the ’20s and ’30s, so now we regarded him with a peculiar ambivalence—awe mingled with horror and disgust. Though we wanted to be grownups or to play at being grownups, weren’t we too young, too fastidious, for such scenes?

Of course there were better things to do on MacDougal Street. There was, for instance, the Minetta Tavern, where Chris and I used to have cozy spaghetti dinners together or with our boyfriends. And then—most fascinating to us—there was the lesbian jazz bar Swing Rendezvous, outside of which a burly bouncer kept watch. Lesbianism was thematic at Hunter High—I’ve mentioned the teachers, but plenty of the students, too, tried to talk the talk and walk the walk. As did Chris and I, venturing now and then past the daunting bouncer to go downstairs and order vermouths with soda. (We were never carded.)

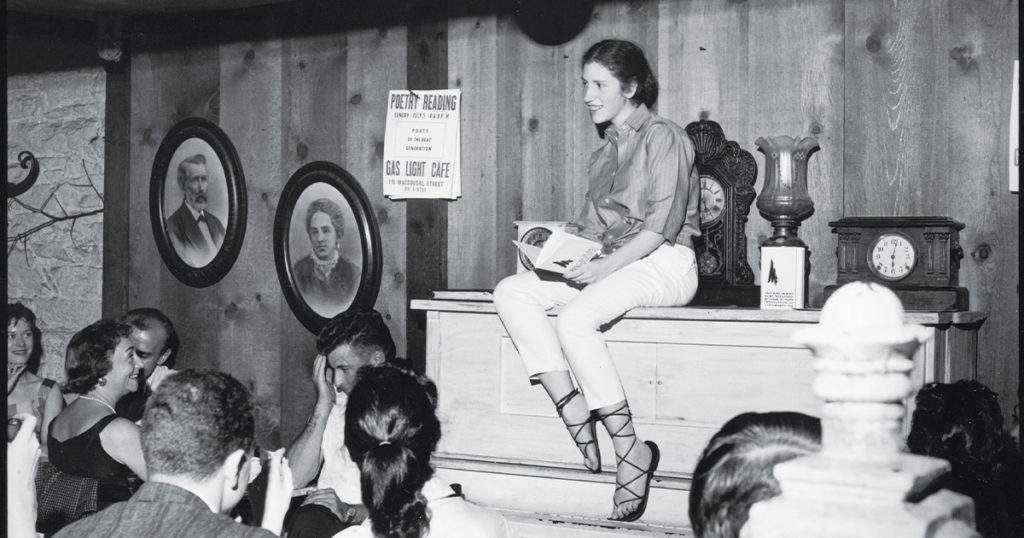

One momentous evening we were astonished, as we entered, to see a familiar figure swaying and singing in the center of the tiny dance floor. Diane! Her red hair was floating, as in “Kubla Khan”; she was sylph-like in tight pants (were they white or were they blue jeans?) and a flattering white shirt. By this time, she had graduated and was said to be living somewhere in the East Village, not far from where Audre lived. I think we were so surprised that we hung back in the shadows, too shy to remind her that she knew us from Argus. Unruly though we were, we were merely visitors to this world, tourists, whereas she was a habitué, a citizen. As, we would learn, Audre also was.

Years later, we were to find out much more about our enigmatic, mystical schoolmate. Like so many of us at Hunter, Diane di Prima was born to immigrant parents (Italian, of course), and was encouraged to go on to an elite college, Swarthmore. But Prima hated Swarthmore, “the pretentious, awkward intellectual life, clipped speech, stiff bodies, unimaginative clothes, poor food, frequent alcohol, and deathly mores by which I [found] myself surrounded.” Nor did she find solace in most other options open to her. “Nine-to-five was a prison; family was prison. Cold intellect of campus, another prison.” Seeking, like her early idol John Keats, the life of art and “the Holiness of the Heart’s Affections,” she wrote that she chose “the life of the renunciant … outside the confines and laws of that particular and peculiar culture” of the ’50s. Dropping out of college, she left home and settled into an impoverished but freethinking bohemian life. In her fictionalized autobiography Memoirs of a Beatnik, di Prima described (maybe truthfully, maybe not) “a strange, nondescript kind of orgy” with Allen Ginsberg, who slid “from body to body in a great wallow of flesh”: “It was warm and friendly and very unsexy—like being in a bathtub with four other people.”

Di Prima had no feminist vocabulary at that point, yet she knew perfectly well that the poetry scene she had entered was male-defined, sometimes “pompous, self-righteous,” but she believed that “we walked together on the roads of Art. … And seeing it thus made it possible for me to walk among these men mostly un-hit-on, generally unscathed.” While so many dutiful ’50s girls were seeking boyfriends, lovers, or potential husbands, di Prima defined the men around her as “friends and companions of the holy art.”

According to Recollections of My Life as a Woman, her realistic 2001 memoir of New York in the ’50s, she had many lovers. The first person with whom she fell in love was a woman named Bonnie, and the second was the African-American poet LeRoi Jones. Even before these passionate affairs, though, she had decided at the age of 22 to have a baby: “I do remember … the words in my mind: That if I didn’t have a baby I was going to get sick,” she recalled in her memoir, adding, strikingly, “Not that I for one minute thought of including a man in my life, in my home. That was out of the question. … As far as I could see, all they were was trouble.”

She wrote about that early, rebellious pregnancy with the same insouciance she brought to her performance at Swing Rendezvous and to her frequent poetry readings. Here’s her charming “Song for Baby-O, Unborn”:

Sweetheart

when you break thru

you’ll find

a poet here

not quite what one would choose.I won’t promise

you’ll never go hungry

or that you won’t be sad

on this gutted

breaking

globebut I can show you

baby

enough to love

to break your heart

forever

After giving birth to her first daughter, Jeanne, di Prima raised her while co-editing a literary newsletter, The Floating Bear, with Jones. Working in a Village bookstore, founding the Poet’s Theater with a group of friends, entering into a marriage of convenience with Alan Marlowe (it lasted six and a half years), she published her own poetry and eventually mothered four more children. Her deeply erotic relationship with Jones was intense and vexed. When it began, she wrote, “She defined herself as a duo: herself and the child. She defined herself as her work. … Stepped into the ‘love affair’ not knowing where it would lead.”

Where it led might, from some perspectives, seem disastrous, but from di Prima’s point of view, it was essential to remain “self-defined in the midst of it all,” even infidelity. “Roi slept around, he lied. … He didn’t show up when he said he was going to, showed up unexpectedly, treated me like a peer, a queen, a servant. … All that went without saying, I took it as it came.” And then, despite his protests—for he was already married, with two children—she bore his child, her second daughter, Dominique, on her own.

“Often he would call me Lady Day,” di Prima wrote of her time with Jones, when they would make love to the music of Billie Holiday, “especially the fiercer, sadder pieces”; but she confesses, “At that time I was only half aware that the songs carried the bitterness, the dilemma of our ‘interracial’ love,” though she knew “there was no world where it was simply okay for us. Not for our black and whiteness. Not for me, a single woman with a child.” Her memory of her time with Jones, who would later change his name to Amiri Baraka and in the ’60s become part of the Black Arts movement, dramatizes the significance of African-American culture in the ’50s—a culture whose feminist exponent Audre Lorde would become.

Chris and I knew Audre better than we knew Diane. She too came from an immigrant (Caribbean) family, and strong though she was, she was quite warm when we were all working together on Argus. One of her first poems, the sort of pseudo-Millay sonnet that we were all writing, appeared in Seventeen in 1951. Here is the octave:

I am afraid of spring; there is no peace here,

The agony of growing things is in my veins.

Where they shall bury me (no tears, no sad refrains)

Shall be none of this frightening green, grass-fear.

If I could only dream of other winters

Or of the summer, clean and promise fulfilled!

Long other springs wherein I’ve waited hinder.

The voice from out the earth cannot be stilled.

A classic lyrical “feminine” voice, even seeking to rival Millay (for that’s how ambitious Lorde was).

Soon after commencement, though, Audre (who had been Audrey in Seventeen) changed radically. I remember the first time we went to visit her in her after-graduation East Village flat. She had always been fierce, yes, but the person who greeted us at the door was beyond fierce. As I recall, she emerged from the shadows of a candlelit room dramatically robed in African prints (a long dashiki, an impressive turban) about whose significance she immediately lectured us. She was, and was not, the Audre we had met at Hunter, the Audre who had dressed like most of the unruly rest of us (black turtleneck and, yes, hoop earrings). Now, though she was still the proud, intense person di Prima described, she was suddenly transformed through her passionate allegiance to her Black heritage. As she told us, “I have found my people!” And in doing so, of course, she had defined herself as a new kind of unruly poet and as the sort of feminist-Africanist preacher, prophet, and warrior she eventually became.

But membership in The Branded had shaped her insurgency, as it had shaped di Prima’s. In her lyrical memoir Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, Lorde wrote that she and that “sisterhood of rebels … never talked about those [racial] differences that separated us, only the ones that united us against the others”—meaning the more decorous girls (to be honest, there were a few of those at Hunter), the girls who weren’t writing poems and touring the Village and fighting the rules set in stone by guidance counselors, Latin teachers, and righteous parents. Even though those in The Branded were almost all white and apparently quite oblivious to racial differences, their boldness armored Lorde, helped her to become—in the course of her career—angrier and far more unruly than anyone could have imagined. Zami, published in 1982, is a work of mature and magical retrospection, but the poems Lorde began to write after high school and college were, to use the title of one of her collections, Cables to Rage—and yearnings for the potent matrilineage of the African goddesses Afrekete and Yemanjá.

In attempting to repossess Yemanjá, the great mother divinity of the African heart of Brazil, she begged

Mother I need

mother I need

mother I need your blackness now

as the august earth needs rain.

And in “Coal,” a more ambitious poem, she exuberantly asserted

I

Is the total black, being spoken

From the earth’s inside.

There are many kinds of open.

How a diamond comes into a knot of flame

How a sound comes into a word, coloured

By who pays what for speaking. …As a diamond comes into a knot of flame

I am black because I come from the earth’s inside

Take my word for jewel in your open light.

Though as a girl Lorde had sometimes experienced her Blackness as a vulnerability—especially because her mother and her older sisters were lighter skinned than she was—she now saw coal as the diamond heart of darkness and demanded to be nursed by “blackness … as the august earth needs rain.”

Di Prima and Lorde were brilliant, unruly girls I actually knew. But there was another unruly girl I had never met who wrote a story with a dark vision that unnerved me. Sylvia Plath was a regular contributor to Seventeen, where Lorde had been so proud to be published, and where I too once appeared in print. According to her bio note, Plath lived in the town of Wellesley, Massachusetts, just the sort of bucolic American place for which I had yearned in childhood. And as I was later to learn, she was a diligent, hard-working student, a daughter of German immigrants whose behavior was in no way unruly. And yet—and yet.

I must have been around 14 when I came upon her extraordinary piece in that usually bland teenager’s journal. Even its title—“Den of Lions”—was shockingly theatrical in the fluttery, pastel context of Seventeen. For a reader like me, brash adventuress though I thought I was, it was unnerving, implying that the world-to-come was dangerous and scary, far more disquieting than Remo or Swing Rendezvous or the political musings of Partisan Review.

Even the teaser was scary: “The crowd was older, more sophisticated. And Marcia was their meat.” And just one interaction between Marcia and a boy named Peter (not her date) summarizes the mood of the piece.

Peter was staring at the red poppy in her hair. “Is that a real flower, Marcia?” he asked with a suave, oily smile that said: Watch this, kids.

He had her cornered. No matter what she thought to say, it would be meat for the sacrifice.

For some reason, I never forgot this story. When as a young professor I began working on Plath—long before libraries considered issues of Seventeen worth saving—I asked my mother and my aunt in New York to go to the Seventeen offices and get a copy for me. It seemed to me to predict a great deal of Plath’s mature work, although she herself was characteristically embarrassed by it. Even so, it might have been clear to her that the irony, cynicism, and general anomie of the story pointed toward just those qualities in her one extant novel, The Bell Jar. In this semi-autobiographical account of her summer at Seventeen’s older sister, Mademoiselle, she recorded the unruly doings of “Mlle’s” guest editors during the overheated month of June when the Rosenbergs were electrocuted. (Following in Plath’s footsteps, I was one of those student editors four years later, working with Cyrilly Abels, the same editor Plath portrayed as “Jay Cee.” And I can testify that there was indeed something unnerving about the experience, so that I actually felt ill when I first read The Bell Jar.)

For a long time, Plath had hoped to write a novel in a “fresh, brazen colloquial voice,” like Joyce Cary or, as it ultimately turned out, J. D. Salinger. And certainly her narrator in The Bell Jar, Esther Greenwood, has just the sardonic perspective on the world that Holden Caulfield has. But even darker: without Holden’s contempt for phonies, Esther is as bizarrely alienated as Marcia in “Den of Lions” from the culture in which she finds herself drifting toward self-immolation. The first sentence of the book sets its tone: “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.” (Esther was in New York because, like Plath herself, she had won that prestigious guest editorship.) But even before she begins to explain why she’s there, Esther continues to obsess about the Rosenbergs:

The idea of being electrocuted makes me sick, and that’s all there was to read about in the papers. …

I kept hearing about the Rosenbergs over the radio. …

I knew something was wrong with me that summer, because all I could think about was the Rosenbergs and how stupid I’d been to buy all those uncomfortable, expensive clothes, hanging limp as fish in my closet …

Esther’s preoccupation with the Rosenbergs isn’t surprising. She is beginning a sort of novel-memoir about the ’50s, with all that decade’s McCarthyism and anti-Semitism—an anti-Semitism promoted even by the Jewish lawyer Roy Cohn, the prosecutor who sought the death sentence for the Rosenbergs and who was later to become Donald Trump’s personal fixer. Ethel Rosenberg’s electrocution was especially scandalous, since there was little evidence that she had participated in the espionage engineered by her brother and her husband, so she is even more important to Plath. Her electrocution introduces a theme that is central to The Bell Jar : the dangerous misuse of electric shock therapy—from Plath’s point of view an analog of electrocution—which she herself was to undergo, with terrible results, in 1953.

Esther’s adventures, during what ought to have been a triumphant month in New York, are all misadventures. She admires the managing editor for whom she is interning, deeming that Jay Cee “had brains”—but she is put off by the editor’s “plug-ugly” looks. Among her sister guest editors, she is drawn to two opposites: the rebel Doreen and the all-American Betsy, whom Doreen labels “Pollyanna Cowgirl.” Together with her widowed mother—a teacher of shorthand and typing, who urges Esther to learn the same skills—these figures might seem to represent different facets of herself or different roles she vaguely aspires to. But at the same time, not one of these women is adequate to her secretly stirring ambitions. In fact, together they are imprisoned in a world that is literally poisonous. All the guest editors—except, tellingly, for Doreen—are felled by food poisoning from a luncheon hosted by the magazine Ladies’ Day. How did Doreen survive? By skipping what was meant to be a treat. But she too had earlier vomited and passed out from too much alcohol, supplied her by a boyfriend she picked up in a taxi.

Nor are the men Esther encounters adequate to her desires. Her college boyfriend, Buddy Willard, is as bourgeois as her mother, and his mother is even more culture-bound. Mrs. Willard strives to marry Buddy to Esther while also urging Esther to become a cookie-cutter cookie-baking ’50s housewife. “What a man is is an arrow into the future,” Mrs. W. opines, “and what a woman is is the place the arrow shoots off from.” But what Esther wants is to be herself an arrow into the future. In any case, Buddy doesn’t present her with anything sexually attractive. When she finally gets a look at his genitalia, the first set of male reproductive organs she’s ever seen, she likens them to “turkey neck and turkey gizzards.” As for the other men she gets involved with—a Peruvian who tries to rape her, a passive simultaneous translator, a math professor who deflowers her (and triggers a massive hemorrhage)—all have nothing to offer while embodying everything to fear.

Esther’s anomie arguably signals the oncoming mental breakdown that will require shock treatments and hospitalization in the second half of the novel. But it’s also clearly a consequence of just the “normlessness” described by the sociologist Émile Durkheim in his famous study Suicide (1897). Such normlessness, a breakdown of previously agreed-on standards and values, increasingly characterized the apparently smug culture of the ’50s—and no doubt inspired the unruliness of my high school friends and me.

Consider, after all, Esther’s colleagues in New York, at home, and later in the mental hospital. Each represents an entirely different way of being. In a world that idealizes the Betsy types—and Betsy was eventually to become a cover girl—rebellious Doreen continues to flourish, Esther’s helicopter mother supports herself by teaching stenography at a university, Mrs. Willard propounds the platitudes of Good Housekeeping, and Jay Cee is powerful but unattractive. All different, yet each in her way as problematic a cultural image as any of the others. No wonder Esther finds herself riveted by what she calls “my vision of the fig tree,” under which she imagines herself sitting, its fruits traditionally representing female vulvas and here symbolizing the range of roles represented by the women around her; as she is unable to decide which fig to choose, each withers and falls to the ground.

After she has sleepwalked through her month in New York, Esther throws away all her fancy new clothes—the costumes of ’50s womanhood—and goes home to spend her days trying to kill herself, finally almost succeeding by swallowing a bottle of sleeping pills and entombing (or enwombing?) herself in her mother’s basement. Not only has her normless month in New York driven her to this Grand Guignol gesture; her first encounter with electric shock therapy, badly misapplied, is a calamity prefigured by the horrifying fate of the Rosenbergs. In “The Hanging Man,” one of her Ariel poems, Plath was also to write about this experience: “By the roots of my hair some god got hold of me. / I sizzled in his blue volts like a desert prophet.”

When Plath wrote all this grim stuff in the early ’60s, she didn’t define herself as a feminist. Nonetheless, she and her work, in both prose and poetry, prefigure what was to become ’70s feminism, an alienation from rigid female roles that had been brewing among the unruly girls of the ’50s, including a nauseated response to sexuality—both virginity and its loss. By one of those quirks of fate out of which futures rise, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published a month after The Bell Jar appeared in the United Kingdom in 1963 and a little more than a week after Plath killed herself. Both books can be said to struggle with what Friedan labeled “the problem that has no name,” and together, along with Kate Millett’s Sexual Politics, they birthed ’70s feminism, as did Plath’s compelling life story.

When The Bell Jar first appeared in the United States in 1971, it was rightly seen as an analysis of just the ’50s culture against which ’70s feminists were rebelling. As in some story of time travel, Esther Greenwood herself might be seen as a ’70s feminist, complete with ambition, anger, and an awakening consciousness, transplanted to the ’50s. Together with such poems as Plath’s “Daddy,” which takes on the “marble-heavy” image of a patriarch, and “Lady Lazarus,” which announces the rebirth of a fiery woman, the novel names on every page the problem that has no name.

And the rest of us—unruly girls like Chris and me, Diane and Audre—did we grasp that problem? I think Chris and I did, at least half-consciously: our Village wanderings could be understood as searches for a world different from the one we encountered in, say, the pages of Seventeen or Mademoiselle, a world in which dating didn’t mean being thrown to the lions and unruliness didn’t mean merely rebelling against stupid rules but discovering new structures. As for Diane and Audre, they were both already making their way toward a future they had begun to imagine—a future in which a young woman could have a baby on her own and a range of lovers of her own choosing.

As for Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, with its breakdowns, its madness, its electrocutions, shows how trapped she was in the troubling culture of the ’50s. Unruly in her imagination, she didn’t begin to be personally unruly until later, in her 20s, when she went to Cambridge on a fellowship, slept around, and drew blood, biting Ted Hughes on the cheek when he ripped her earrings off the first time they met.