This September marks 20 years since that day when the New York sky blazed true blue, the towers crumbled in a cloud of dust, and a book saved my life. The book, a teal, clothbound edition of Giambattista Vico’s On the Study Methods of Our Time, was first published in 1709, but translated and published in English in 1965. A call number on a rectangle of yellowed paper glued to the lower left corner of the fraying cover reads “LB57 5V5 A213 1965 (LC).” My boyfriend (now husband) checked it out for me on September 8, 2001 from the Cross Campus Library at Yale, where he had recently finished his master’s degree in music theory. I was, at the same time, in graduate school for philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York City. Classes had started for the term just a week before. I was also in the midst of a painting residency at the World Trade Center, painting cityscapes from vacant office space on the 91st floor of the North Tower. I had spent the whole summer in the tower, newly in love with Manhattan and the strange geometry of rooftops seen from on high.

My plan had been to paint all morning on September 11, getting to the World Trade Center as early as possible, and then to leave just in time for my graduate seminar on Hans Georg Gadamer in the afternoon. I was scheduled to be the first presenter in the class. Gadamer invokes Vico early in his massive Truth and Method, in a section devoted to sensus communis, or “common sense.” I remember being moved by the generosity of Gadamer’s text the first time I read it—the spirit of curiosity and indebtedness to thinkers who came before him. I felt that I would need to read the entire history of philosophy to fully understand him. Short of that, I needed Vico.

I already thought of Vico as a kindred spirit—not knowing he would also become my guardian angel. I first encountered him in a graduate course on the sublime, where we had to read an excerpt of his 1725 text, The New Science. The section had to do with the origins of language. Vico invents his own creation myth about primitive and wildly creative childlike giants who communicate through grunts, shouts, and murmurs. Imagining the sky to be a vast animate body, they shout to it as if it might reply. But a terrible storm arrives, with flashing lightning and deafening claps of thunder. The giants, thinking the sky must be punishing them for their clamor, avert their eyes and hide in silence. From that point onward, they are forever humbled and transformed into human scale. They lose their boundless poetic natures and have to muster a new courage to speak and to look up. I liked the idea of Vico sitting somewhere in Italy, imagining the beginnings of humanity in the shape of those sublime giants. How sad and sweet to think of the moment when a giant feels so scared that he forgets his size and, cowering under a rock, gives up his babbled poems.

I needed my Vico book for class on September 11, and, leaving my apartment on Clinton Avenue in Brooklyn, I descended to the C train only to discover that I didn’t have it. A fateful moment of indecision as the train approached. Rather than board, I left the platform and went up to street level again, wasting a subway fare, then back to the third-floor apartment where my roommates were still asleep, returning back down again to the dim tracks and a later train, the slim, tattered book in hand. Twenty minutes of painting time lost, was all I could think.

Twenty minutes’ difference between arriving at the plaza of the World Trade Center around 8:20, taking the elevators up to the 78th floor and transferring to the second bank of elevators that run to the top, getting out in the carpeted, gray hallway on the 91st floor (always too cold), walking toward the oversize gray, metal door that led to the gutted, but utterly beautiful vacant space lined on three sides with perfectly rectangular, human-sized windows through which beams of golden light were cast on the floor. Instead, my train was still rumbling underground at 8:15, still in the tunnels and the caves at 8:30. I only emerged into the sunlight again at 8:40 or so to walk across the plaza to the base of the gigantic North Tower just at 8:45—to the same revolving doors where all summer my easel or other gear would get jammed as I tried to go around, and a security guard would ask to see my badge but knew me by now as the girl with the paints.

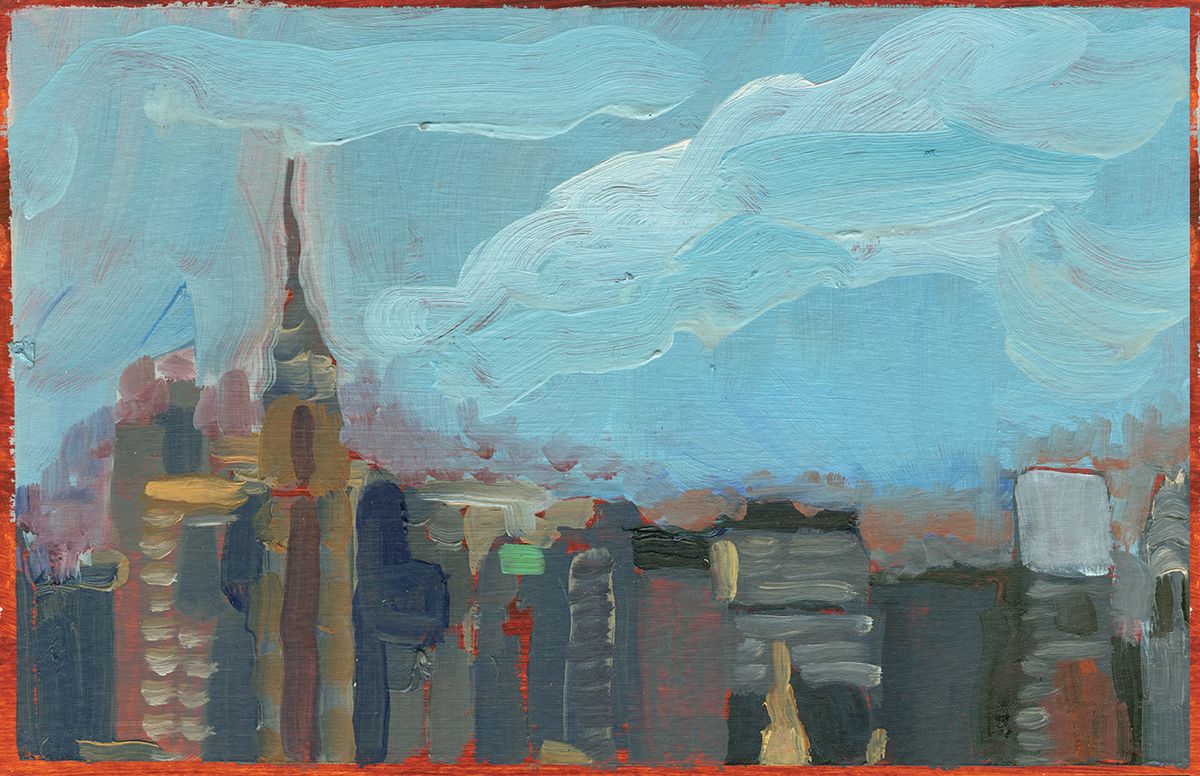

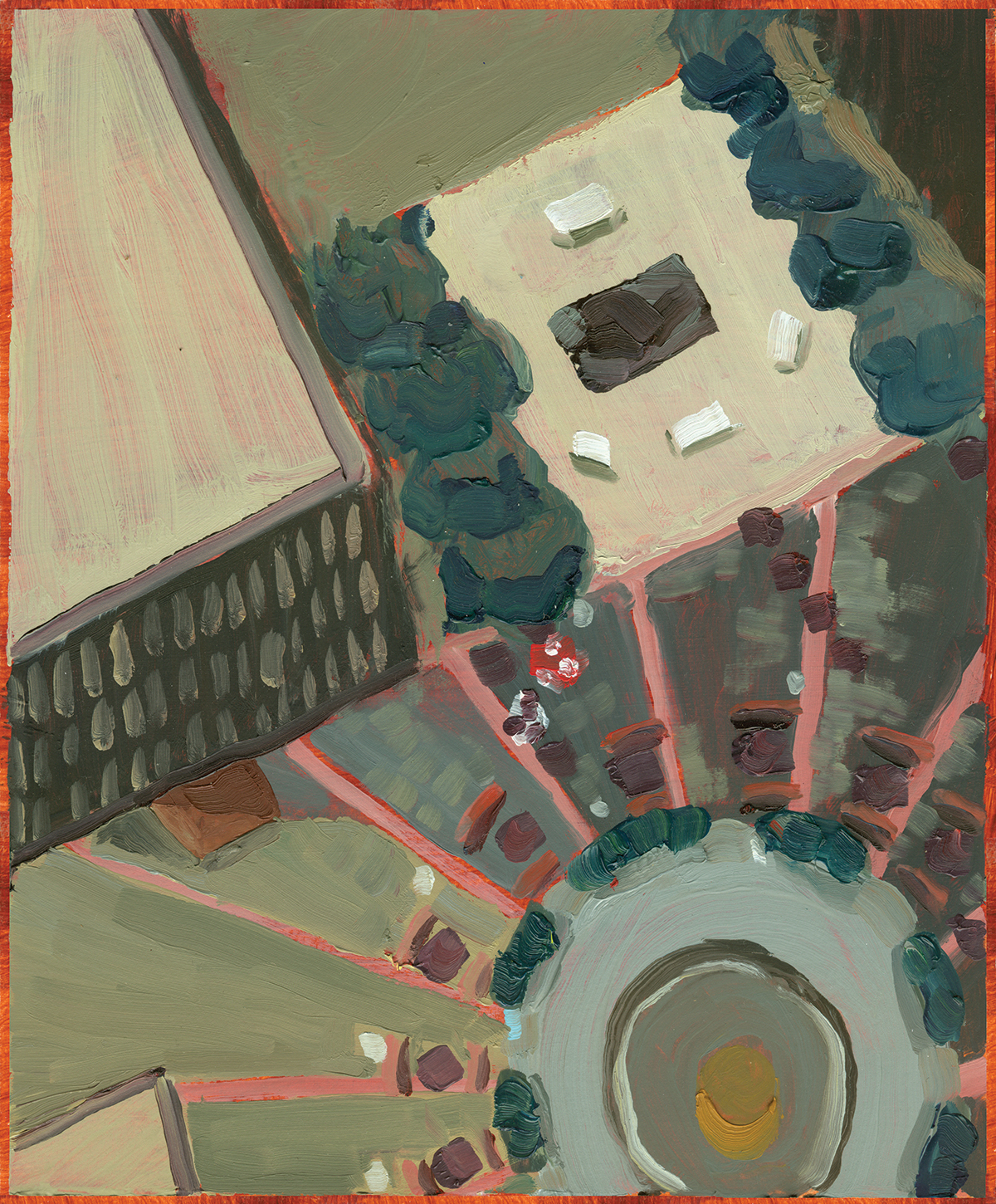

Mostly I remember the blue of the sky, the miracle of summer light as I emerged from the train. I loved so much about New York in the months leading up to September 11, all of it related to painting the city. I have always felt that you can paint things into lovable shape, especially those things that most resist your affection. The city was that way for me. A hard, unforgiving span of concrete and bricks. Humorless, without hope. But through painting, the buildings, and then the city, softened and changed. A smear of Payne’s Grey, some dabs of pink. The sky went on for miles from up high, the streets disappeared under a patchwork of rooftops, each one a secret composition of its own. Everything was quiet and still and spread out like an intricate quilt from the height of the 91st floor, and I couldn’t wait to pick which corner of things to transcribe, which water tower or bank of trees, purple shadows or the tops of Yellow Cabs so far below like Tic Tacs in a line. In late summer, walking those same streets at ground level, I had secret knowledge about the tops of things that made them seem goofy and humane.

I loved the hot plaza at the base of the towers, with its red umbrellas and concrete planters full of magenta flowers. I loved the anonymity of eating my lunch there, watching tourists and all the people in suits converge on the same place, some of them gazing up in disbelief because you never got used to the height of the buildings stretching up into the sky. And even though it was overly air-conditioned and freezing inside, I loved the rush of heat as you exited the lobby, finally down on the ground again, at human scale, pulling off the layers I would wear to stay warm while painting.

From inside, I loved the early morning, when the building was quiet, and especially dusk, when the whole city turned a deep blue—and yellow lights rhythmically appeared in windows one by one, or sometimes in whole banks of gridded squares. Traffic lit up like Christmas lights along the West Side Highway, followed by the twinkling aqua lights of the Williamsburg and Brooklyn Bridges. I loved the ways the tower would heave and sigh, sometimes buried in a bank of clouds. Late at night, the halls were vacant, and I went down, reeking of oil paint, in the elevators alone. I fell in love with the sky, and the tower came to seem like a person: awkward, lonely, majestic.

That summer, I took photographs from the tower. This was before average people had cell phones with cameras, but I had a decent 35mm Olympus that required old-fashioned film. Most weeks I’d complete a roll and leave it to be developed at a small camera shop in the mall below the World Trade Center. I never painted from photographs, but I liked to have a snapshot of the views I had tackled or shots of the city in interesting weather or at night. I have a small box where I keep those pictures along with my ID badge, still strung on a slim metal chain, a penny flattened and stamped with a picture of the Twin Towers, the key to the studio, a $5 prepaid phone card I purchased later in the morning on September 11, and a tag for film I had dropped off on August 21, 2001 (yellow with a picture of the Twin Towers in the logo and a note that says “envelope 019043”) but never was able to retrieve. The Vico book stays on a shelf. A card glued to the back page has stamps for just two previous times it was checked out: “overnight reserve fall term 1974” and “JAN 3 1997.” A small receipt tucked into a pocket inside the back cover notes the lending details and the due date, March 8, 2002. After years of notices and overdue fines, I finally bought the book.

I can’t remember if I was still holding Vico in my hand when I crossed the plaza that day. I know I was wearing flip-flops and torn, paint-covered pants. I know that on the subway that morning I had been standing near the door and a young girl in pigtails seated across from me was carefully eating Sour Patch Kids, licking the sugar dust from her fingers and swinging her feet. I know I exited the C train onto the plaza rather than into the mall, and I crossed the expanse of stone in the bright sunshine to the doors at the base of the north tower, oblivious to the sky. I know that after leaving the lobby and looking back, there was a hole like a horrible gash at exactly the height where I imagined the studio should be, and people, larger than I thought possible, in and around the hole and flying or falling through the sky. It’s an image I will never forget for as long as I live, the black suits against the crystal sky. And I know there was a large Black woman right behind me at some point, and her mouth was open so wide that it looked like a mirror image of that other impossible gash, her eyes full of terror. I turned around and locked eyes with her for a moment, and then I knew it was real. I remember buying the phone card to use a pay phone, going into a bodega at the northeast corner of the plaza, where people were pushing and frantically buying disposable cameras, and then waiting in line to use the phone for what seemed like an eternity while the world seemed to be crumbling all around, eventually dialing the number of my apartment, and telling my roommate that I was okay just as the tower peeled away from itself in a slow-motion rush of billowing gray like nothing I had ever seen, hurling itself downward (it seemed to go on forever), bringing what seemed like the entire sky with it, and sending up the most tremendous, hulking cloud of dust that came rolling with people everywhere ducking and running and all of it catching everything in a metallic snow, and I thought I am breathing them now, the people who were just a moment ago at the hole 93 stories up.

And why in that moment were my feet wet? I don’t know. And why was I thinking about my dad, trying (failing) to imagine him in a dark suit? And why did a beautiful girl with dark hair and kind eyes reach out and touch me and ask if I needed help? And why did someone else offer me their shoes? Why did I start walking north rather than head into the rubble to help or to dig or to die? I remember the cowardly feeling, most of all and to this day, of wanting to get away, wanting to live. I remember the dust on my feet mixing with the wet and forming a gray cake, a walking tomb. I remember, eventually, the sight of the Empire State Building up ahead of me and the feeling of panic and not wanting to go near it, crouching in a doorway, seeing it reaching up into the sky and knowing now what it would look like for it to peel and crash at my feet, for a hole to open in things without warning on a perfect summer day.

I did not yet know about the planes, about Pennsylvania, or Washington D.C., or anything else. It’s strange to have been there but to have known so much less than those farther away who would see the images looping on their televisions, images I have managed to avoid seeing for 20 years. We will never know the same things. I still thought (insanely) perhaps it had been the turpentine in the studio—an explosion I was somehow responsible for. I still thought (insanely) I might go back later that day to get my things—the tin box of brushes given to me by my first painting teacher, the U2 CD, my easel, my camera, clamp lights, my smock, a favorite sweater, 20 or so oil paintings in progress lying on the floor. I knew the buildings were in a heap. I knew the rubble was on my hands and feet. But a mind can only hold a small bit of reality at one time, thank god.

How could I know that three years later I would be standing in a field at my grandparents’ farm marrying the man who checked out the Vico book for me (and who had flown from New York to Boston on the night of September 10, 2001, kissing me goodbye in the rain on Bleecker Street)? Or that five years later all of my grandparents, starting with my Grandma Ulmet, would die in quick succession, leaving another hole in the world, the last of them lying in a hospital bed with a morphine drip and my mom and I at his side and a bank of gray trees outside the window standing attention in the bleak cold? Or that eight years later I’d give birth to my first daughter, and 12 years later give birth to my second? Or that 19 years after September 11, 2001, my brother would be diagnosed with colon cancer in the middle of a global pandemic, and I would be pulling down a mask at his bedside in a hospital in New Jersey to kiss him and he would be brave? Or that 20 years on, an apartment building in Florida would slide into the ground overnight in a familiar, leveling fit of gravity and ash?

I couldn’t know. Crouched in a doorway a few blocks away from the Empire State Building, the sky its brilliant blue, I knew so little even though I knew things I could not ever again unknow. I was still, for a time, in the margin of the missing, a part of me forever stranded in that in-between. But looking back, it feels in some way like one hard thing replaces another even as nothing goes away. Life is too full to stall in a doorway. The shock recedes 20 years on, and what a gift to move through the world anonymously and unwounded from the outside, not to have to endure the stare or questions of someone who knows too much of the story (“where were you?”), to be able to forget.

And in the long wake of wreckage, lights shimmer. Dull at first, then brighter. The night gets less scary, the images blur. Stairs and heights and even the smell of fire recede into a place like the photos and the key in the box under my bed. The trails of glistening traffic wind up Fifth Avenue like jewels in the city’s black casement. Bits of songs echo in my head—Ellis Paul, a singer-songwriter I had heard once at the Boston Folk Festival when I was in high school, suddenly playing his guitar and singing at the top of his lungs in the plaza of the World Trade Center on a summer evening just before (the night before?) September 11; holding hands in a circle on the green of a small town in Connecticut a few days afterward, trying to muster “Amazing Grace,” but unable to utter “a wretch like me.”

World Trade Center Plaza by Megan Craig, 2001, oil on paper, 10 X 7 inches

Fifteen years later, my daughters would ask me to read them The Man Who Walked the Towers, a book they found at the library. We’d settle into a cozy place to turn the pages and be each time amazed (and a little aghast) at Phillipe Petit, the tightrope walker who stretched a cable between the towers on the morning of August 7, 1974, and walked between them. The girls were always worried that he’d end up in jail when the police arrived at the roof of the towers, yelling at him to come down. But each time, as if they had never heard the story before, they would giggle and clap when he ended up safely on the ground, only sentenced to the “community service” of entertaining children with puppet shows in the park. And each time as we turn the last page to the last picture of the towers, I know something they don’t know yet (and I think maybe that is what survival is: knowing something you don’t tell), and I try as hard as I can to imagine the tightrope and the walker and the happy ending where he balances there for hours and then gleefully, safely, comes down.

I have been told only recently that there is a part of the September 11 memorial that includes swatches of blues representing different memories of the sky on that day. Every now and then a September day comes that matches my own memory, the sky a solid cerulean without a cloud, the summer heat edged with a sense of fall. And all I can do is shudder and hope that everything remains where it should in the sky.

I guess I am like those pathetic giants Vico described as terrified of the sky—cowering in their place, feeling the might of the gods’ fury in thunder and lightning coming from above, while they remain rooted to the earth, at the mercy of gravity. Things fall down. A universal law. Perhaps that’s why I’ve always loved Emily Dickinson’s lines: “It was not death / for I stood up / and all the dead lie down.” It is enough to stand, to ward off the fall with some minimal gesture of resistance, day after day. You don’t even have to lift your head, let alone your eyes. Forget the poetry and just stand up. There is a strange weight of being spared that day, gifted more skies, more gravity, the miracle of walking away intact. People call it “survivor’s guilt.” But it seems more pedestrian and lowlier than that. Sometimes it’s heavy, the burden of a life so randomly elected and feeling that it should amount to something more, something important. Mostly it’s unyielding and ordinary just to wake, to dress, to go out, to be alive.

And what I want to say, I think, is that 20 years is both long and short. Long enough for forgetting, for newness, for other skies—and barely the blink of an eye. Those buildings stretching up into the vault of blue like ladders to heaven, the piles of ash and the smell of the burning (for weeks, for months, forever), the before and the after, the instinct to live, the touch of death—all of it mixes like a dense fog that clears away miraculously in the right weather and returns every September like dust settling into cracks, like a chorus in a Greek play, like a swarm of gray birds on the field, startled and darting in a pitch of wings and cries.

This year will be no different. Except every year has its own shape. At first I could only picture the straight vertical lines of an 11, those ones standing side by side just like the towers did at the southern tip of the island. Twenty years on, numbers and dates have softened. On the 16th year after September 11, I remember thinking: my experience of that day is now old enough to drive! Maybe it will get a car and finally hit the road. On the 18th year, I thought: now it is officially adult, ready to leave home. Will it head off to college now? Can I drop it off? And here, at 20, like a child who fails to launch, it is still with me more or less, still vying for attention and taking up valuable real estate, still needy and hungry and young.

Well so be it. I have softened too. Twenty years is a long way to come and to hold, with all the love and anguish one can muster, the memory of those gleaming beams of steel, the hardness and softness of it all, the beauty and brutality. I am a place of safekeeping. And I tell myself, Crouch if you must under the glare of things too high. The echinacea toppling over in early September, the first leaves going gold, the smell of pavement in the rain. The shape of a date, the beams of light, the bluest skies scrubbed and clear, waiting.