The Israeli singer and composer Chava Alberstein, who was born in Szczecin, Poland, to Yiddish-speaking parents, sings a lovely song called “Don’t Need Much,” in which she recites a list of her mother’s oft-repeated bon mots. My favorite is, “If you have to choose a pain, better a stomach-ache than a heart-ache.”

But what do we actually experience when we say that our hearts ache, or that a song “pulls at our heartstrings” or “sends shivers down our spine”? Does the phrase “butterflies in my stomach” indicate some sort of physiological reaction, or is this expression, like the others, only metaphorical? A new Finnish study suggests that we really do experience certain emotions in specific parts of our bodies.

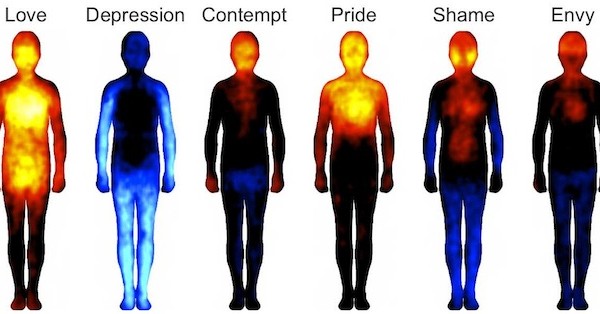

Lauri Nummenmaa, a cognitive neuroscientist, and his colleagues at Aalto University in Espoo, Finland, conducted experiments in which they showed participants silhouette images of the body and asked them to color those regions that were most active when they experienced different emotions. (Movies, stories, facial expressions, and words served as the stimulus for the emotion.) The research team found that distinct emotions were reliably associated with discrete regions of the body: anger in the chest and arms; disgust in the throat and gut; envy in the head; love in the head, chest, arms, and abdomen; and happiness all over.

To check that these bodily sensations were not merely a reflection of local language or culture, the researchers compared the reactions of Swedish and Finnish native speakers (Swedish being a Germanic language, Finnish belonging to a very different family of languages called Uralic). They discovered that the “bodily sensation maps” drawn by participants were similar in both samples, as were those sketched by members of an additional group of Taiwanese speakers of Hokkien, a language far removed from Finnish.

Previous work, the researchers note, has demonstrated that facial expressions of emotion are associated with changes in heart rate, finger temperature, and muscle tension, depending on the emotion. But most people are dimly aware, if at all, of most such physiological responses. The bodily sensation maps drawn by participants reflect in part the influence of the autonomic nervous system, which controls body temperature, heart rate, the workings of the gut, and our “fight or flight” response—a system we are not consciously aware of.

The Finns’ findings are more than just a curiosity; the research may help them understand the emotional unraveling that occurs during depression and anxiety. “We will next address whether bodily sensations of emotions or bodily sensations in the absence of external emotional events are altered in mental disorders,” Nummenmaa wrote to me via email. “In the future this may provide diagnostic tools for detecting such disorders.”

“Don’t Need Much” suggests that Alberstein knows the meaning of heartache without the aid of a bodily sensation map. Toward the end, she sings,

My mother is no longer here

But I am her daughter

I still remember, still heed

Still believe.

In the early mornings

I cry

And in the night I sing

And play for you.