Leaving Orbit: Notes From the Last Days of American Spaceflight, by Margaret Lazarus Dean, Graywolf Press, 317 pp., $16

Human spaceflight has always lent itself to escapist fantasy. Popular TV shows and movies depict humans gliding comfortably through the void in climate-controlled starships with pleasingly streamlined interior design. An alien civilization intercepting this deluge of images might think that we had achieved the technology necessary for long-distance spaceflight many years ago, that we are just light-years away from warping into their galaxy, à la Captain Kirk and crew.

Indeed, it’s tempting to think of this kind of spaceflight as inevitable. Yes, NASA’s space shuttle program ended in 2011, without any plans for a government-funded replacement. But Russian Soyuz spacecraft still carry American astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS), and Elon Musk’s privately owned SpaceX has said it will launch a crewed commercial mission to the ISS by 2017. To the outside observer, it would seem that humanity’s migration to the stars is proceeding on schedule.

Leaving Orbit aims to puncture this easy fantasy. In her Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize–winning account of the last days of the space shuttle program, University of Tennessee English professor Margaret Lazarus Dean argues that we lost something special when NASA retired its remaining shuttles: Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour. “I’ve never been a believer in privatized spaceflight,” she writes. “Getting to space as cheaply as possible with an emphasis on catering to paying customers only serves to rob spaceflight of the things I love most about it.” Her book is a moving evocation of those things and an argument for why we, too, should treasure them.

To Dean—also the author of a novel about the Challenger disaster, The Time It Takes to Fall—NASA programs have always had much loftier goals than just breaking free of Earth’s gravity. At their best, as with the Moon landings, they unified the country in the name of scientific discovery rather than war. That Americans have let all this go without protest (or without even noticing) Dean finds deeply troubling. “The public needs to know that American spaceflight stopped, and to feel sad about that, before they will clamor to rebuild it,” she writes.

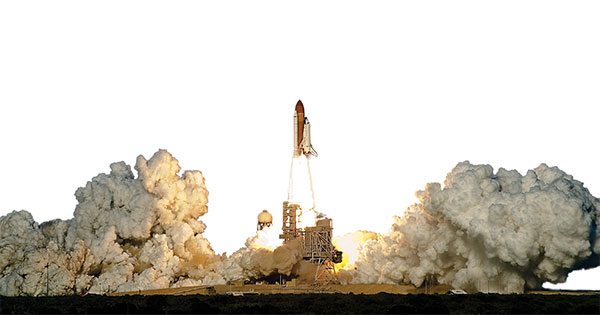

Writing Leaving Orbit is Dean’s way of sounding the alarm. She anchors her narrative in a first-person, on-the-ground account of the final three launches of the NASA shuttle program. For the launch of Discovery, she joins a crew of “space fans” who watch from a causeway near the Kennedy Space Center grounds. Attacked by “vicious mosquitoes,” wilting under the Florida sun, these stalwarts wait nine humid hours for a glimpse of the rocket. Even later, when Dean gains access to a viewing point inside the Space Center for the Endeavour launch, the experience is much the same: a lot of sweating and waiting around in lawn chairs. Star Trek it isn’t.

The physicality of Dean’s descriptions extends to the launch itself. She is struck by the light of the ignited rocket on the launchpad—“different in color, quality, and intensity from any other kind of light”—and by the way it “fad[es] into the ever-fattening steam column that billows up” as the shuttle rises into the sky. For her, a shuttle launch is a stirring aesthetic experience that dwarfs all other human enterprises in ambition and scale.

Take the scene in which Dean watches Atlantis emerge from storage atop “the world’s most powerful ground vehicle.” Weighing 11 million pounds with its cargo, the mobile launch platform rolls to the launch pad three miles distant at a rate of half a mile per hour, all the while belching “a toxic cloud like the idling of a hundred eighteen-wheelers.” Seeing how much effort goes into this process, Dean is skeptical that startups like SpaceX will ever manage to perform NASA-like feats.

Yet, despite repeated declarations that the end of the shuttle means “the future is cancelled,” Dean gives readers of Leaving Orbit little sense of what that future might have been. We learn that rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun had a plan to assemble Mars-bound spacecraft in low Earth orbit, aided by a theoretical space station that was never built. But that vision dates back at least to 1969, and it feels odd that there are no more recent projects to mourn. Science fiction might have helped fill the gap, but the only work Dean cites at any length is Jules Verne’s 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon. To some degree, her nostalgia for the distant past reduces her book’s power—it’s hard to lament the cancellation of a future whose nature is never made clear.

But maybe it’s unfair to impose this burden on Leaving Orbit. Ultimately, Dean has set out to document a historical moment, not write a polemic or a policy paper. And in that she has succeeded. Several times in the book, Dean mentions her envy of Norman Mailer, whose interviews with the Moon-bound Apollo hero-astronauts for Life magazine were later incorporated into his 1970 book, Of a Fire on the Moon. “Sometimes it seems as though Norman Mailer’s generation got to see the beginnings of things and mine has gotten the ends,” she complains. But a good ending to a story is often harder—and more important—to write than the beginning, and Dean has made an honorable effort. The only remaining question is whether what she’s written is really an ending at all.