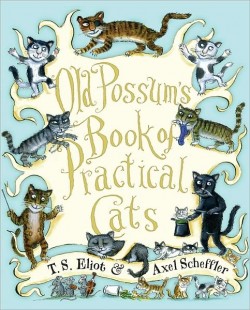

Poets traditionally own cats. Baudelaire would caress his “beau chat” and, being Baudelaire, daydream about his Creole mistress’s pliant body. T. S. Eliot famously celebrated the entire species in the comic verse of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. As a Sherlockian, I’m particularly partial to Eliot’s Macavity, his feline Napoleon of Crime, sometimes known as “the hidden paw.” Christopher Smart’s greatest poem, “Jubilate Agno,” memorably extols the virtues of his cat Jeoffry, that “excellent clamberer.”

Poets traditionally own cats. Baudelaire would caress his “beau chat” and, being Baudelaire, daydream about his Creole mistress’s pliant body. T. S. Eliot famously celebrated the entire species in the comic verse of Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. As a Sherlockian, I’m particularly partial to Eliot’s Macavity, his feline Napoleon of Crime, sometimes known as “the hidden paw.” Christopher Smart’s greatest poem, “Jubilate Agno,” memorably extols the virtues of his cat Jeoffry, that “excellent clamberer.”

When a young gentleman was said to be going around 18th-century London shooting cats, Samuel Johnson—in Boswell’s words—“bethought himself of his own favourite cat, and said, ‘But Hodge shan’t be shot; no, no, Hodge shall not be shot.’” He wasn’t. Later, when the poor creature did lay dying, Johnson gave it valerian to ease its agonies.

My own particular feline companion answers, or rather doesn’t answer, to Cinnamon. One of my kids must have given her the name, even though she’s mostly gray and white. Originally a stray we took in, the old girl has been a valued member of the household for at least a dozen years. Once, Cinnamon was a mighty huntress, roaming up and down the world at night, seeking whatsoever she might devour—or bring home and lay reverently, as a gift, on the back doorstep. But at some point, the wear and tear of nocturnal outings—of nature red in tooth and claw—became too much for her. I think she suffered a run-in with a fox or lost one battle too many. At all events, she now stays pretty much inside, sleeping in sunbeams and mewing for food twice a day.

In truth, I’m not really a cat person. Seamus, the wonder dog, still deeply mourned by all who knew him, was just about the only pet I’ve ever really loved. He died about a year ago now. I always found walking around the block with this happy yellow Labrador among the best parts of the day, a time to clear my head, a time to find new energy and ideas. I miss him. Best dog ever.

Were I more ambitious in the pet department, I would keep tropical fish. Like most people, I find watching the lazy and quiet underwater realm of a big aquarium exceptionally calming. Didn’t someone say that he could happily live with the fishes? Was it Whitman? It certainly wasn’t Luca Brasi, the Godfather’s protector: sleeping with the fishes is quite different. I’ve just checked, and it was Walt, but not fishes—“I think I could turn and live awhile with the animals … they are so placid and self-contained.”

I’ve never been attracted to songbirds. Canaries and parakeets seem so fragile. Dorothy Parker, it’s been said, named her canary Onan because he spilled his seed upon the ground. Now and again, I do think a parrot might be interesting, and it would be fun to teach it to squawk a bit of Pirate English: “There’s none can save you now, missy.” Still, a parrot sounds like more work than a tank of fish. And dirty, too. The English critic Cyril Connolly kept lemurs—but they were very dirty, and in a fecal way.

Many years ago, I knew a beautiful blonde who acquired a pet pig, one that followed her around like a dog. It was rather unnerving. Of course, pigs are quite literary creatures: We have Dick King-Smith’s Babe and E. B. White’s Wilbur and the pigs of Animal Farm, some of whom are more equal than others.

Because of Kipling, I’ve sometimes wondered about keeping a mongoose about the house. But given the cobra population in Silver Spring, Maryland—zero, when last I checked—we hardly need a Rikki-Tikki-Tavi. Still, maybe it would frighten away the deer who eat the flowers and shrubs and the bark from our young trees. As it is, my wife has begun speaking darkly about acquiring a hunting bow. Neither Rudolph nor Bambi would be spared if she has her ruthless way.

Last, but not least, there are horses. Yet somehow these noble quadrupeds don’t strike me as pets, despite every young girl’s passion for a pony or a palomino. The animals seem too massive, too demanding, and as expensive to maintain as an old Jaguar XKE. William Buckley once summarized what it was like to own a sailboat: stand fully dressed in a cold shower, he said, and tear up hundred dollar bills. Owning a horse appears to be a comparable business. Forgive me, Flicka, Black Beauty, Misty of Chincoteague, and all you other heroic steeds.

Of course, children’s literature is a virtual petting zoo. What kids’ book doesn’t feature an animal, usually a dog? There’s Clifford, Big Red, Lassie, Lad, Shiloh, Buck, Ol’ Yeller, and on and on. There are more exotic animals too, such as Henrietta, the 266-pound fowl beloved by Arthur Bobowicz in Daniel Pinkwater’s The Hoboken Chicken Emergency, or the eponymous protagonist of My Father’s Dragon, by Ruth Stiles Gannett. Joan Aiken produced a delightful series, exuberantly illustrated by Quentin Blake, about a girl named Arabel and her troublesome raven Mortimer. While Beatrix Potter’s little albums are all about animals—especially naughty ones, like Peter Rabbit and Squirrel Nutkin—her woodland characters aren’t really pets. They’re children in disguise.

In my youth I envied Lord Greystoke (sometimes known as Tarzan of the Apes) for myriad reasons, but partly because of his animal helpers and companions—above all, Jad-bal-ja, the Golden Lion. Still, the most glorious, if unfortunate pet in literature is probably the tortoise in J. K. Huysman’s decadent classic, A Rebours (Against the Grain). The novel’s hero, Des Esseintes, encrusts its carapace with gleaming jewels, then sends this ground-level chandelier lumbering through his mansion’s shadowy rooms. Alas, the sad creature, weighed down by diamonds and emeralds, soon sickens and dies.