I never collected books in a serious way until my mid-20s. On a long-ago trip through upstate New York, my then-girlfriend (now my wife) and I happened to call on an old bookseller named Roger Butterfield. Probably enchanted by Marian, Butterfield invited us to have coffee in his specially built “office”—it was half book barn, half gentleman’s study, and completely wonderful. I yearn for something like it to this day.

I never collected books in a serious way until my mid-20s. On a long-ago trip through upstate New York, my then-girlfriend (now my wife) and I happened to call on an old bookseller named Roger Butterfield. Probably enchanted by Marian, Butterfield invited us to have coffee in his specially built “office”—it was half book barn, half gentleman’s study, and completely wonderful. I yearn for something like it to this day.

In the course of the afternoon, this former Life magazine journalist suggested a half dozen books about books that I should read and, being a docile young man and eager to learn, I went out and read them. These included David Randall’s Dukedom Large Enough, an elegant memoir of the author’s years working in Scribner’s rare book department; Charles Everitt’s lively and opinionated Adventures of a Treasure Hunter; and Edwin Wolf and John Fleming’s sober biography of that dealer in only the rarest of literary rarities, A. S. W. Rosenbach. Later, in Washington, I enjoyed Percy Muir’s reprinted radio talks on collecting and John Carter’s magisterial lectures, Taste and Technique in Book Collecting. One day I even bought my own copy of Carter’s ABC for Book Collectors, among the most entertaining of all lexicons.

These days I don’t read very often about the “gentle madness,” as my friend Nicholas Basbanes dubbed collecting in his case-studies of the affliction. But I still keep a straw basket by my bedside loaded with a dozen or more “books on books,” and these I pick up from time to time, usually at the end of a long day. At the moment that basket contains the following:

Indexers and Indexes in Fact & Fiction, edited by Hazel K. Bell

Iris Murdoch, A Writer at War: Letters & Diaries. 1938-46, edited by Peter J. Conradi

The Glory That Was Grub Street: Impressions of Contemporary Authors, by St. John Adcock (“With thirty-two camera studies by E. O. Hoppé”)

Ian Hamilton in Conversation with Dan Jacobson

The Folio Book of Literary Puzzles, by John Sutherland

A Book of Booksellers: Conversations with the Antiquarian Book Trade, 1991-2003, by Sheila Markham

In Pursuit of Coleridge, by Kathleen Coburn

London Library, edited by Miron Grindea

Second Reading: Notable and Neglected Books Revisited, by Jonathan Yardley

What Can Be Saved from the Wreckage? James Branch Cabell in the 21st Century, by Michael Swanwick

Arnold Bennett: The Evening Standard Years, Books & Persons, 1926-1931, edited by Andrew Mylett

The Pleasures of Reading, edited by Antonia Fraser

Seeing Shelley Plain: Memories of New York’s Legendary Phoenix Book Shop, by Robert A. Wilson

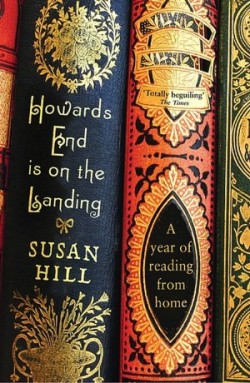

Howards End is on the Landing: A Year of Reading from Home, by Susan Hill

As you can tell, I have a distinctly Anglophile penchant. Just recently I finished The Acceptance of Absurdity, a chapbook containing the letters between English novelist Anthony Powell and American bookseller Robert Vanderbilt, mostly concerned with the publication in the United States of Powell’s early comic novels Venusberg and Agents and Patients.

The English do carry on the best literary correspondences. Just recall, for instance, the wildly funny epistolary exchanges between Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford or the hilarious, politically incorrect, and often moving Letters of Kingsley Amis, many of them to poet Philip Larkin. Of course, no serious Anglophile book-lover should be without The George Lyttelton/Rupert Hart-Davis Letters—the book-chat of a former Eton master and a noted London publisher, both of whom are extremely well read, gossipy, and often grumpy about the state of the modern world. I reread one of the six volumes every few years. Just as good, and with an American slant, is Memorable Days, the correspondence between novelist James Salter and literary journalist Robert Phelps. Don’t miss the introduction.

These days, The Paris Review has repackaged its long-running series of conversations with authors, and even made them available online. I’m glad for this, and yet the original Writers at Work volumes, especially the first three, possessed a magic all their own. As a teenager, I virtually memorized my paperback editions, greedy for insider tips about the literary life. Pound, Eliot, Hemingway, Faulkner, Colette, Waugh—they were all there. What has stuck with me the most over the years is their almost universal insistence on the importance of revision, of revising and revising again. Georges Simenon provided one of the most inspirational interviews: he began by saying that Colette had warned him that his early stories were “too literary” and from that moment on he cut out adjectives, adverbs, and any word that was there just to make an effect. Needless to say, I treasured those underlined and asterisked trade paperbacks, keeping them in a little nook on my bed’s headboard, just above my pillow. I probably hoped they would work some subtle Muse-like influence while I slept and one day I would awake a writer. It goes without saying that I was a weird kid.

And some would say I’m a weird adult. Despite the rising popularity of the downloadable e-text, I still care about physical books, gravitate to handsome editions and pretty dust jackets, and enjoy seeing rows of hardcovers on my shelves. Many people simply read fiction for pleasure and nonfiction for information. I often do myself. But I also think of some books as my friends and I like to have them around. They brighten my life.