“Bound to Respect”

How Black and white reformers transformed the meaning of the Dred Scott decision’s most infamous line

Rarely does the language of a Supreme Court opinion enter the American lexicon. Perhaps the most famous phrase in Supreme Court history is, “You have a right to remain silent.” Of course, all good television- and movie-watching Americans know this by heart, although they may not know that its source is Miranda v. Arizona (1966). The phrase “separate but equal” from Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) has also entered the American vernacular, perhaps mostly because of the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which outlawed segregation in public education.

In the mid-19th century, most Americans seemed to know one line from the Dred Scott decision (1857) by heart: Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s claim that at the time of the nation’s founding, African Americans “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The line was paraphrased repeatedly during the Civil War era. Between 1857 and 1867, it was quoted or paraphrased at least two dozen times in speeches by members of Congress. On the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives in 1861, for example, Rep. Thomas D. Eliot of Massachusetts described the scene in coastal South Carolina after the Union captured Beaufort and Hilton Head and the Confederate civilians had fled: “No white man is there, nor is there any one there except those of whom it has been said that they have ‘no rights which a white man is bound to respect.’”

African Americans also often quoted it in public statements, as did William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator. Antislavery advocates sought to turn Taney’s language against proslavery forces. For example, an 1858 Black suffrage convention in Troy, New York, resolved, “That the Dred Scott decision is a bold and infamous lie, which neither black men nor white men are bound to respect.” Others quoted or paraphrased Taney from memory for non-racial reasons. Union veteran John D. Billings described soldiers “who sat over the fire in the tent piling on wood all the time, and roasting out the rest of the tent’s crew, who seemed to have no rights that this fireman felt bound to respect.”

Taney’s aphorism became controversial from the moment he uttered it, and a sharp public debate arose over what exactly he meant. Many interpreted it to mean that Black Americans had no rights that white Americans were bound to respect in 1857, not in 1776 when the Declaration of Independence had been written. During a January 1862 debate in the U.S. Senate over the rights of slaves who were being jailed by the federal marshal in the District of Columbia, Jacob Collamer, a Republican from Vermont, said, “I have understood that the Senator [Lazarus Powell of Kentucky] belonged to the school which held to the doctrine of the Dred Scott decision, that a negro or person of African descent had no rights that a white man was bound to respect.” Senator Powell replied, “I never understood the court to decide such a thing.” Powell maintained that Taney was only alluding to political rights. James A. Pearce, a Maryland Democrat, agreed with his border state colleague. “The Chief Justice never said a negro had no rights which a white man was bound to respect. The Chief Justice knew perfectly well that in every slave State of this Union, certainly in that State of which he is a citizen [Maryland], a negro has many rights which a white man is bound to respect, and which the courts enforce.” Instead, according to Pearce, Taney “spoke of the opinions which had prevailed in regard to this subject race, and the manner in which they were treated; and he said there was a period when men seemed to think there were no rights belonging to a negro which a white man was bound to respect. Who can object to that language? That was his language as I aver. I know it well.”

How is it that this particular line—out of a 56-page opinion (and a case that runs 243 pages in the Supreme Court’s published reports)—could gain such notoriety among the American public? It may be that most white male voters agreed with the sentiment, or at least found it politically attractive. Upon deeper reflection, however, it seems more likely that the phrase stuck out because it ran counter to two deep-seated ideas or values in American society at the time. First, it conflicted with the oath of office taken by federal judges (including Chief Justice Taney) to “administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich.” In denying that white people in 1776 owed “respect” to the rights of Black people, Taney seemed to be using his position as a federal judge to deny the administration of justice “without respect to persons” (and it should be noted that the U.S. Constitution always referred to enslaved people as “persons,” never as “property”). Second, Taney’s words seemed to allude to—and contradict—the Christian Gospel. In Acts 10:34-35, the Apostle Peter said, “Of a truth I perceive that God is no respecter of persons”—meaning that He does not show partiality toward one person or group over another. In short, Taney was claiming a privilege for white Americans that not even Almighty God would exercise.

Americans of the 19th century knew the words of the Apostle Peter by heart—so much so that they paraphrased it in their ordinary language. One soldier, for example, wrote that lice and mosquitoes were “no respecter of persons.” Slaves and their abolitionist allies had, in fact, long looked to this passage as a source of hope. In 1837, the soon-to-be-martyred Elijah P. Lovejoy told a mob of pro-slavery Illinoisans, “For remember the Judge of that day [God on Judgment Day] is no respecter of person.” In 1843, Reverend Henry Highland Garnet quoted Acts chapter 10 in his oration “An Address to the Slaves of the United States of America,” as did Frederick Douglass in his famous speech “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” when he argued that proslavery theology “makes God a respecter of persons, denies his fatherhood of the race, and tramples in the dust the great truth of the brotherhood of man.” Likewise, John Brown quoted the verse in his address to the Virginia court that convicted him of treason in 1859. It is little wonder that abolitionists, white and Black, took particular note of Taney’s remarkable language.

During the war years, white antislavery advocates continued to connect the Apostle Peter’s words with the abolition of slavery in the United States. One Union soldier who was convalescing at the U.S. Army hospital at Quincy, Illinois, wrote in a letter to his family that “millions of the downtrodden and oppressed of this earth are soon to swell the song of freedom and it will continue till it is reached by all nations, God is no respecter of persons, and he is not always going to permit man to oppress his fellow man.”

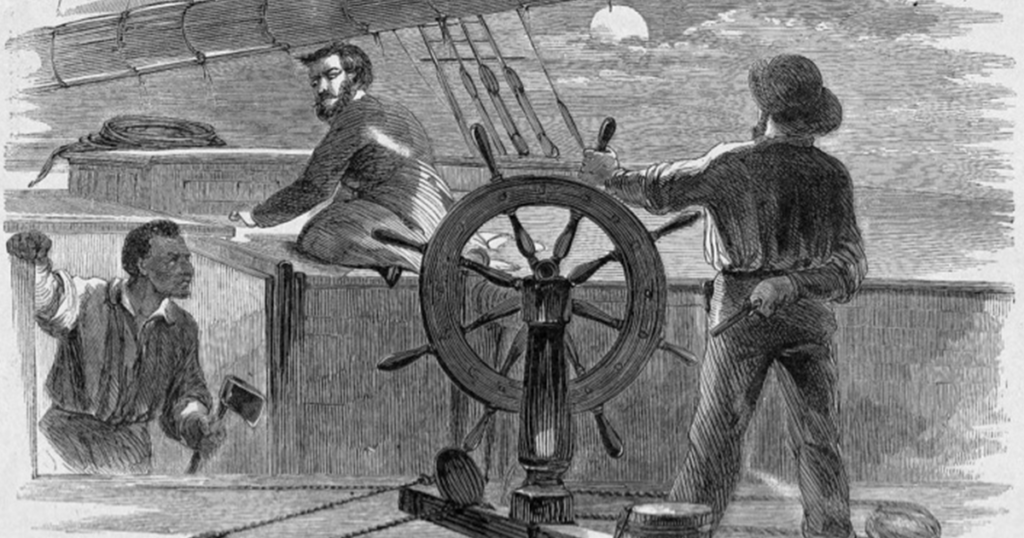

As the war began to move toward freedom and rights for Black Americans, white abolitionists reveled in the changes they saw taking place—and they appropriated Taney’s words to signify that his dictum was no longer the law of the land. The abolitionist editors of The Liberator rejoiced when William Tillman, a free black sailor from the North, mutinied and killed Confederate privateers who tried to kidnap him on the high seas so that they could sell him into slavery. Tillman himself ultimately profited from the affair when a federal court in New York awarded him a significant sum in the fall of 1861 for salvaging the Confederate ship. The Liberator’s editors wrote with pride, “[I]t will be recollected that Tillman belongs to that class of persons who, according to Southern expounders of law, have no status in a United States Court, and no rights, either, which a white man is bound to respect.”

In Edinburgh, Scotland, abolitionist Eliza Wigham published The Anti-Slavery Cause in America and its Martyrs in 1863 to help persuade England not to recognize the Confederacy. The “infamous piece of judicial villainy called the Dred Scott decision,” she wrote, included the “sweeping” declaration “that ‘black men have no rights which white men are bound to respect.’” Wigham called this statement “a bold and impious attempt to defy the declaration that God hath made of one blood all the nations of men.” “Alas!” she concluded, “the white men have had to learn by bitter experience that GOD is no respecter of persons, and that He himself can plead the cause of the oppressed, and by terrible things in righteousness can arise to punish the oppressor and the unjust judge.”

In moments when African Americans overcame significant hurdles during the war, the words of Roger B. Taney immediately came to their minds. But instead of being bruised and oppressed by them, Black leaders used them for their own purposes, quoting them back to white society to show how far they had come. In 1863, Robert Purvis told an audience, “Sir, old things are passing away, all things are becoming new. Now a black man has rights, under this government, which every white man, here and everywhere, is bound to respect. That damnable doctrine of the detestable Taney is no longer the doctrine of the country.” Purvis’s words were met with loud applause. After being brutally attacked by white civilians in Maryland in May 1863, black Union officer Alexander T. Augusta found military officers to arrest and detain his assailants. He then wrote in a public letter that his ordeal “has proved that even in rowdy Baltimore colored men have rights that white men are bound to respect.” Black writers and their allies used Taney’s language to prick the conscience of the nation when the federal government denied equal rights to African Americans. In protest of the unequal pay that Black soldiers received, one Vermonter wrote indignantly, “But the colored troops, hav[e] no rights which Congress or anybody else is bound to respect.” What Taney had meant for harm became a rallying cry for equality during the war.

Frederick Douglass, who grew to have immense love for Abraham Lincoln during the war years, argued that despite Lincoln’s shortcomings, he was “emphatically the black man’s President: the first to show any respect for their rights as men.” Douglass had met with Lincoln three times during the Civil War, and in these meetings he found that the president saw himself as bound to respect the rights of Black people. “Some men there are who can face death and dangers, but have not the moral courage to contradict a prejudice or face ridicule,” Douglass wrote. “In daring to admit, nay in daring to invite a Negro to an audience at the White house, Mr. Lincoln did that which he knew would be offensive to the crowd and excite their ribaldry. It was saying to the country, I am President of the black people as well as the white, and I mean to respect their rights and feelings as men and as citizens.”

During the debates on the 13th Amendment, politicians continued to point to Taney’s language to push for social change. In the ratification debate in Pennsylvania, for example, one Republican legislator quoted Taney’s statement among a litany of evils that slavery had produced over the previous years. Democrats, by contrast, chafed at the prospect of constitutional abolition: “It is no uncommon expression which declares that the [white] people of the Southern States have no rights which the Government is bound to respect.”

Taney’s dictum in Dred Scott gained a place in American culture that is unusual for a Supreme Court decision, but it did so because it ran so counter to values held dear by many Americans at the time. It continues to be frequently quoted by historians—and is perhaps the most widely quoted line from a 19th-century Supreme Court opinion—in large part because of how effectively it was overturned by Black and white reformers in the years after Taney uttered it.