Wisconsin-native Breehan James has spent the past 10 years depicting her home state and the Boundary Waters of Minnesota. A professor at Boston University, James says the works of 19th-century Nordic landscape painters have greatly influenced her own compositions. Here, she discusses how painting from life is liberating, the benefits of immersing oneself in nature, and why the wilds of Wisconsin always refresh her spirit.

“Growing up in the Fox River Valley of Wisconsin, I didn’t know any artists—I didn’t know that was something you could be. But I followed my interest and ended up going to Massachusetts College of Art, where I studied drawing and printmaking. Afterward, I took a couple of years off and then applied to grad school, got in, and went to Yale. Even at that point, I never really thought about being an artist. I’m glad that I didn’t—it’s so hard to make a living. But painting gives me such a strong sense of meaning and purpose. I can’t imagine my life without it. One day I realized, ‘Huh, that’s what I am—I’m an artist.’

Going hiking and camping was always a big part of my life. So for the past 10 years, I’ve been painting out in the wilderness. I spend three or four weeks each summer going out into the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota, moving my studio out into the wilderness. Early on, I wanted to be a representational landscape painter, and I realized that the best way to do that was to paint from life. So that became a liberating experience—if something interested me, I could just sit down and make a painting. I didn’t have to question, ‘What does it mean?’ or ‘What’s the larger scope of it?’ There was no fear. There’s also a particular kind of beauty in Wisconsin and Minnesota—the northern light is gorgeous. It’s a really subtle beauty. Some of my favorite paintings are mid- to late-19th-century Nordic landscape painting, and it’s a similar northern light. I love how those paintings place you on the ground and celebrate Norway and Sweden by depicting these beautiful wilderness areas.

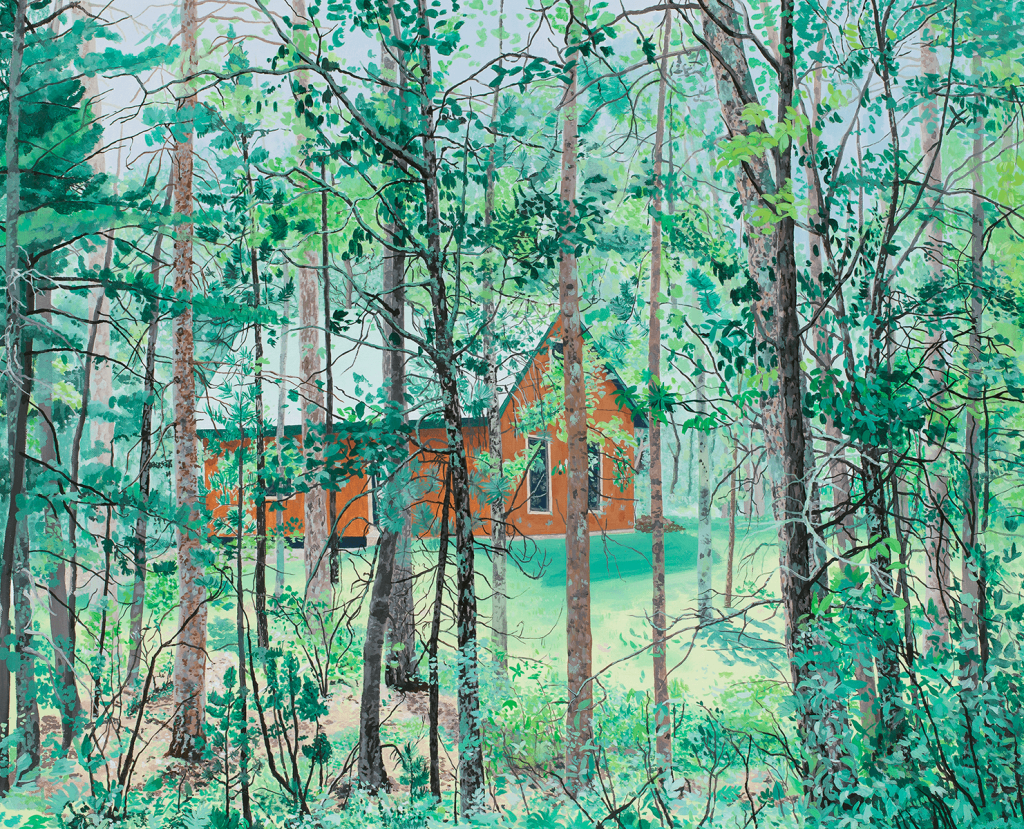

I also like to go up to our family’s cabin in northern Wisconsin. My grandfather built it in the 1960s, and it’s a magical cottage. Now, my whole family shares it. There’s a sense of our family’s history because the cabin never changes. When you go there with family, you feel that people are present—telling stories, cooking food together, and making fires. The experiences I’ve had there with people feel raw and rich. That’s why I go to the wilderness: to look for that and to be refreshed. It gives me peace and tranquility—I feel so renewed. I became interested in making portraits of this place, and through these paintings, I was trying to figure out why this cottage was so important to me. I also had these amazing experiences being immersed in nature that happened in the national forest that surrounds the cabin. Politically, it’s troubling to me that so much of our public land is under threat, and it’s forced me to think about how I can communicate why the land is worth saving. It’s an impossible quest to depict that in a painting, but that’s my new ambition. I hope my paintings can move people—whether that’s getting out and appreciating our public lands or inspiring people to help and save our wilderness areas.”