Multidisciplinary artist Brenda Mallory grew up as a member of the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma and has lived in Portland, Oregon, for more than 20 years. In 2015, she was awarded a residency at GLEAN, a Portland-based art program that encourages artists to create works that draw attention to consumption and waste. Here, she discusses her Reclaimed and Reformed series.

“I’ve always worked with mixed media. I like working with things that are found, rather than buying new things and cutting them up. That’s how I got my start—for an assignment in art school, I started using cloth mixed with wax. I had access to piles and piles of scrap fabric that was basically in the same shape. It’s malleable like clay but not fragile.

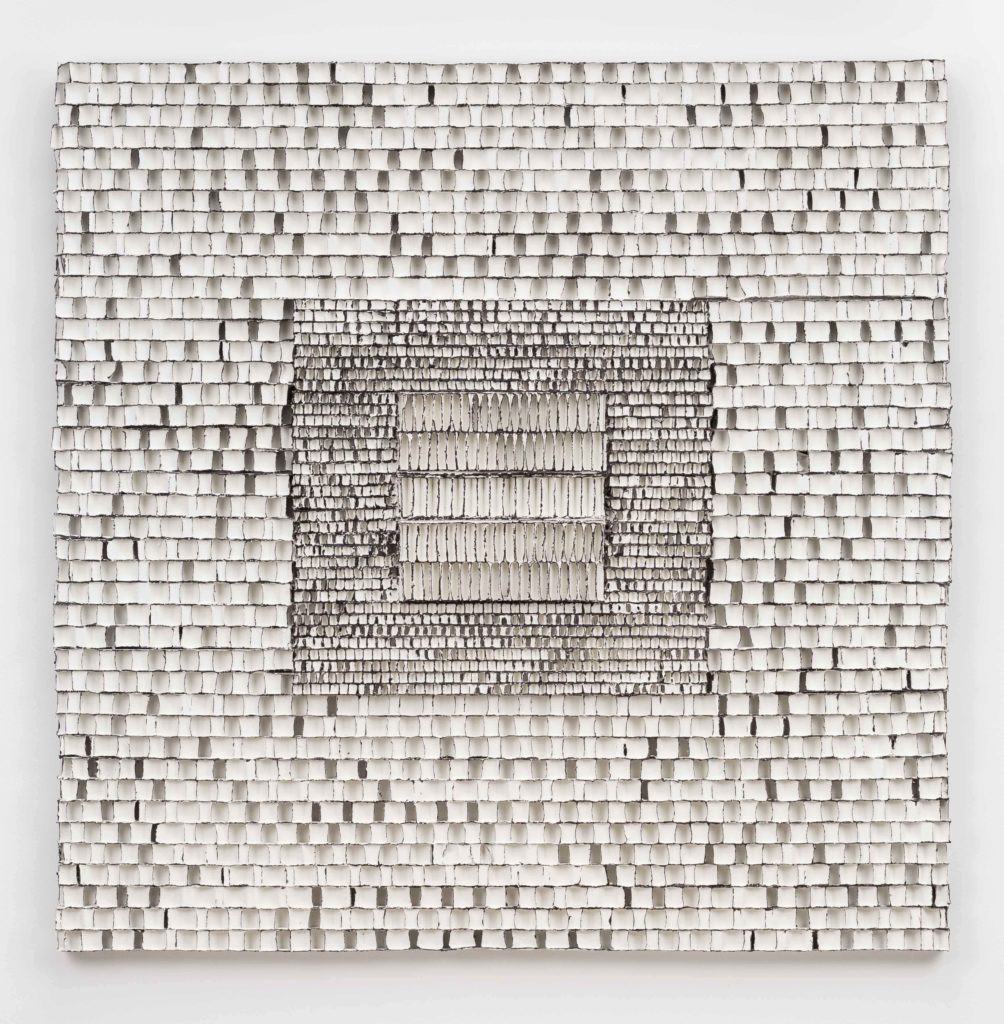

When I was a GLEAN resident, I had five months to work at the local dump. Almost all of the works in the Reclaimed and Reformed series were made from objects I found there. For Reformed Packings #12, I used honeycomb packing material as a substrate. It comes in 4’ x 8’ sheets and is very strong. I reform it so that it becomes fragile, and then I paint it. Drive Belt #1 (Red) is made from drive belts—the ones that are in our car engines.

You would not believe the number of new or perfectly usable things that get tossed into the trash. The fact that we throw this stuff away indicates to me how we devalue labor. All of these consumer goods are somewhere else where labor is cheap—so cheap that we can throw away hundreds of dollars of material goods, only to buy more. The sociology of consumption is built into my series.

I grew up poor. My grannies used to save everything. I still have some potholders that my granny made out of old clothes. Who would do that anymore? Maybe someone doing it in a DIY or crafty way—it’s niche. We don’t need this art that I’m making to put on the wall. But my granny needed those potholders, and cloth was valuable at the time. We didn’t waste anything.

The monochrome palate is because I’m not a painter and fear color. I have been working for a long while with this idea of the ‘broken.’ The broken line or the broken form that gets reshaped and put back together. In my mind, it becomes more interesting because of that—where you can see the repair or the seam along which things were reassembled. For instance, I cut apart firehoses and put them back together. In the pieces, you can see the frayed edge. To me, it’s about disruption. In school, I learned about the disruption of our ecosystems. But as time went on, I kept thinking about disruption on a larger scale—how our cultures are disrupted. Historically, my culture was disrupted by the Trail of Tears when the Cherokee were forcibly moved to Oklahoma. The fact that a whole culture could be uprooted, moved to a new place, and then keep going—it’s incredible.”