I’m still surprised that no one ever told me about the incubator baby kidnapping. To be fair, it happened 63 years before I was born, but it also happened half a block from where I was born, and little Marian Bleakley was perhaps the most famous baby in the country even before she was kidnapped. My great-grandfather’s uncle, moreover, was the county attorney who got the kidnappers convicted. Marian went on to graduate from my high school and attend the college where I now teach. And yet, I’d never heard of her until a few years ago, when I stumbled across a bizarre headline in a digitized newspaper archive: INCUBATOR BABY AGAIN KIDNAPED [sic].

Yes, “again.” It turns out that Marian’s 1909 abduction from her Topeka home was just another chapter in perhaps the most dramatic custody dispute since the one adjudicated by King Solomon—although I may simply be surrendering to that comparison after seeing so many journalists use it. Thousands of articles were published about little Marian between 1904 and 1914—sensationalistic, gossipy, confused, and often contradictory pieces typical of the news at that time. It didn’t help that journalists had landed on one of the most protracted, pretzel-plotted sagas in the history of American weirdness. I’ve probably read 100 of those articles now, and I feel less confident in my ability to tell the true story of the incubator baby than I did after reading the first one. But it’s not going to tell itself.

On February 15, 1904, Charlotte Bleakley gave birth prematurely at the so-called private sanitarium of a St. Louis midwife named Mary J. Merrifield. Bleakley was chloroformed during the delivery and was told afterward that the baby had not survived. She wrote to her husband, from whom she was estranged, requesting money for the burial.

But the baby was still alive. An unwed actress named Edith Stanley had given birth in the sanitarium at the same time, and there had been a switcheroo. Believing that the Bleakley baby was hers, Stanley had left her in the care of the midwife, whose services included arranging adoptions. (Laws regulating adoption at the time were lax, to say the least. Merrifield frequently placed ads in the Sunday Post-Dispatch: “Pretty baby girl and boy for adoption, free.”) But because the two-pound preemie was in danger of dying, Merrifield turned her over to the Imperial Incubator Concession Company, a popular exhibitor at the St. Louis World’s Fair. Visitors thronged the incubator display, drawn to the novel sight of impossibly tiny babies struggling toward viability in newfangled artificial wombs.

In the case of the Bleakley baby, they were also drawn by something else they saw in her face: its seeming resemblance to that of a chimpanzee. A nurse affixed the name “Emily Darwin” to her incubator, a joke that was apparently considered affectionate rather than cruel. Journalists, however, treated the girl’s simian appearance as a phenomenon with serious evolutionary implications: “A constant stream of medical men has been pouring in to look at the latest scientific curiosity, a baby in whom is a living proof of the Darwinian theory.”

“Emily Darwin” grew into a conventionally beautiful baby. One of the exhibitors at the fair, Stella Barclay, became so emotionally attached to her that she relocated her perfume concession to be closer to the incubator. Wealthy and childless, Barclay and her husband inquired about adopting little Emily. By that time, Charlotte Bleakley had learned that her daughter was still alive—though newspapers give multiple, conflicting accounts of how and when the switcheroo was revealed to her. Emily graduated from the incubator, and after a warm exchange of letters with Stella Barclay in November 1904, Bleakley signed paperwork authorizing the adoption. Emily Darwin became Thelma Barclay of Moline, Illinois, the sole heiress to a substantial fortune.

Then Charlotte Bleakley read Les Misérables and, moved by the story of Cosette, decided she wanted her baby back. She sued for custody in Illinois in May 1905, arguing (dubiously) that she had been tricked into giving up the child and (probably correctly) that the adoption contract was invalid under Missouri law. The court ruled in her favor, the Barclays appealed, and while the appeal was pending, Bleakley fled to her home in Kansas with Thelma, whom she’d renamed Marian.

The next several years were a judicial free-for-all, with Kansas, Illinois, and federal courts at various levels awarding custody first to the Barclays, then to Bleakley, again and again. Marian remained with Bleakley despite her ever-shifting legal status, in part because Bleakley kept absconding with her. “Since the litigation commenced the baby has been hurried around the country to prevent the serving of papers on its custodians and has even been kidnaped [sic] on one or two occasions,” the Topeka Daily Capital reported in November 1907. Two months earlier, Stella Barclay and a private detective had tracked Marian down in the tiny Kansas town of Elgin and ripped her from Bleakley’s arms. An angry mob led by Bleakley and her mother pursued the abductors to the train station, and a brief fight followed, in which Bleakley bit a wealthy cattleman. While the authorities tried to sort that situation out, Bleakley again fled town with the girl.

At some point in the midst of all this, the Barclays learned the story of Edith Stanley and became convinced that Bleakley wasn’t Marian’s biological mother. “She was the child of an actress,” Stella Barclay now insisted. “And, by the way, little Marian is the exact picture of her. The strong similarity of features to my mind makes the identification complete.” This was a risky argument for the Barclays to pursue in court because it could have nullified their claim to have legally adopted the girl from Bleakley. But pursue it they did, enlisting Merrifield to testify that Charlotte Bleakley’s baby had, in fact, been stillborn. By this time, though, the midwife had told so many different stories that her credibility was shot. (It’s pretty clear that the sanitarium’s services included illegal abortions, and fear of scrutiny would have made Merrifield evasive.)

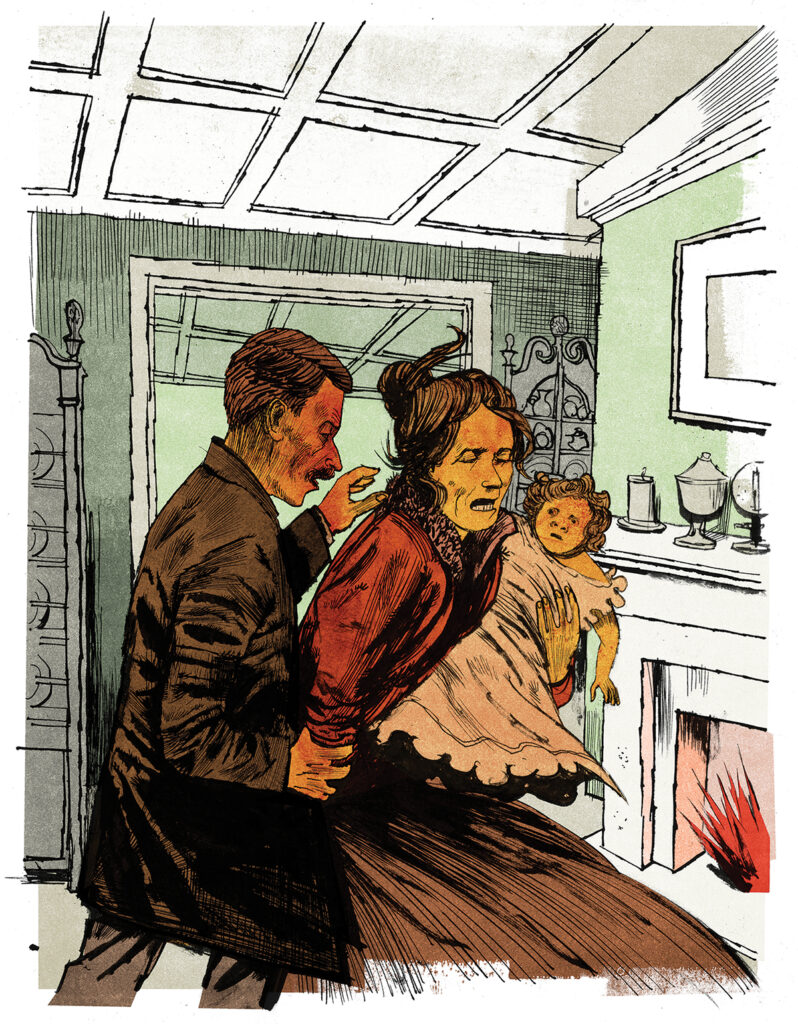

In 1909, Stella Barclay again hired a private detective, Freeman Tillotson, whose employees traced Bleakley and the child (now five) to 1027 Garfield Avenue in Topeka. Tillotson’s people spent several months surveilling the house, going so far as to rent the place directly across the street. On the morning of August 21, with the help of a woman posing as a soap vendor, a Tillotson deputy named Joseph Gentry entered the Bleakley house and pried Marian from the arms of her grandmother. When a visiting cousin of Bleakley’s tried to intervene, Gentry knocked him out with the butt of a revolver. He then carried the screaming child to a nearby car, where Stella Barclay was waiting.

During the subsequent trial, Tillotson and Gentry testified that they genuinely believed they were returning a child to her rightful mother. Ably prosecuted by John J. Schenck, my great-great-grandfather’s younger brother, both men were sentenced to terms in the state penitentiary. Tillotson was later pardoned by the governor, at the urging of a magnanimous Charlotte Bleakley. Charges against Stella Barclay were dismissed, also with Bleakley’s approval. Remarkably, some version of the custody case wandered all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. According to a 1914 article in the Topeka Daily Capital, “The long legal fight for possession of the St. Louis exposition ‘incubator baby’ was dismissed in the supreme court today because neither party to the suit had printed the record.”

The name Charlotte Bleakley shows up in the papers just a handful of times—brief mentions in society-page items—between 1915 and 1977, the year she died at age 97. A scattering of “Where is she now?” notices appeared when Marian got married in 1925, including a couple of lines in Time magazine, and again when she divorced in 1927, but nothing more. One salutary effect of this hard-won irrelevance was that it permitted the family something like an ordinary life. Charlotte and Marian both became teachers. Marian’s brief first marriage produced a daughter. She remarried in 1939, to Howard Adams, a prominent banker and Kansas state senator from the little town of Maple Hill. He was nine years her senior, with a body ravaged by polio and two spinster sisters who suspected that Marian was a gold digger. “And perhaps she was,” says Nick Clark, a Maple Hill native and the town’s unofficial historian, “but people didn’t care. She took really good care of Howard.” He died in 1959, leaving her roughly half a million dollars, on which she lived comfortably for 35 more years.

My brother, who pastored for many years at Maple Hill’s one church, had put me in touch with Clark. He says he grew up with Marian’s three grandsons and spent a lot of time in the Adams house. He vividly remembers Marian and Charlotte, both of them prim and elegant. Marian dyed her hair dark brown but kept a dramatic white streak down the center. He never saw her angry or heard her say an unkind word, but he remembers that she was strict with her grandsons.

The older residents of Maple Hill found Charlotte haughty and affected, Clark recalls, but children adored visiting her. “They had the best library in town,” he says, “and Mrs. Bleakley would have us come in and sit down on the floor, and she’d read from classic children’s books. She would also have little scripts for plays we would act out.”

One day when he and one of the grandsons were playing in the Bleakley library, Clark noticed two big scrapbooks on a shelf. His friend told him they were full of old newspaper clippings: “My grandmother was the incubator baby.”

“I was probably in junior high at the time,” Clark says. “I didn’t think too much more about it.”

Only recently, when he got curious and dug into the archives himself, did Clark learn that there was once a question as to whether Charlotte was Marian’s birth mother. And barring DNA test results from their descendants, he says, he’s not inclined to doubt it now. “Those two women were remarkably alike—the same height, the same body shape, even the same voice. When one was speaking, you had to look to see who it was.”

Ultimately, it’s not surprising that the Bleakleys’ final disappearing act was so, well, final. There was something particularly of-its-moment about the incubator baby saga. Every element of it stirred up anxiety. At a time when science and technology were threatening humanity’s longest-held assumptions about itself, here was a baby being publicly raised by a machine, her evolving appearance seemingly confirming Darwin’s theories. At a time of social unease about the “New Woman” who wanted to get a job and ride a bicycle and vote, here were two women—one married and wealthy, one single and poor—driven to an identical, primal ferocity by the prospect of lost motherhood. It may be that America didn’t so much lose interest in the incubator baby’s story as lose the ability to be interested. Nothing is as quaint as yesterday’s terrifying notions of the future.