Cambodia: Gambling on the Future

Sihanoukville is rapidly being remade into a modern playground for the rich, thanks to investment from China

It’s happy hour in Sihanoukville, a Cambodian beach town on the Gulf of Thailand. Waves lap against the dampened sand beneath sunset beams of gold. Little kids bob on inner tubes; teens take selfies on the beach. I order a glass of wine and drag a lounge chair out from under the casuarina trees. There is something mesmerizing about this hour in the tropics, when darkness falls and the heat dies fast. Another scorching day gives way to a welcome breeze. Right here, right now, humanity unites in its revelry.

But as I glance toward a spit of land that stretches beneath the sinking sun, reality takes shape in the dusk: the jagged silhouette of construction cranes atop skyscrapers still undone. It’s the paradox of where I am—a tranquil sea facing an onslaught of messy development, swaddled in the stench of burning plastic.

The Cambodian coast is changing faster than I can fathom.

I first came to this beach in 1998. I was an editor at the now-defunct Cambodia Daily during a year of historical distinction. Khmer Rouge soldiers waged their final bloody assaults against the government before their experiment in human atrocity finally collapsed. Troops defected. Pol Pot died. Decades of warfare came to an end. Thousands of foreign aid workers inhabited the country at that time, and on weekends, they filled the beaches, together with those Cambodians who could afford to be there. Families gathered on blankets to eat grilled fish and drink Angkor beer. Austere bungalows rented for a few dollars a night, and those with air conditioning went for $25.

By Monday morning, most visitors would be gone, leaving the beaches empty. The coastline was a strip of sand edged by jungle-covered hills. No high-rise condos existed then, no casinos aglow in neon lights. My favorite restaurants served fresh crab in black-pepper sauce, and my husband and I would eat and drink until the town went dark. The frogs were the loudest partiers around.

That was then. Today, Sihanoukville—named for Cambodia’s late, beloved king—is rapidly being remade into a modern playground for the rich, thanks to foreign investment from China, which as the region’s great power is seeking to extend its political, economic, and cultural influence. This city and its surrounding coastline are crucial components of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a plan for global development that the Council on Foreign Relations has called “the most ambitious infrastructure investment effort in history.” Between 2016 and 2018, Sihanoukville reportedly sucked up $1.1 billion in Chinese investment, and all told, coastal infrastructure projects worth some $4.2 billion reportedly have Chinese backing. In 2018, Chinese tourists here numbered two million, an all-time high. An estimated 30 to 40 percent of Sihanoukville’s rising population is Chinese. (Cambodia’s most recent census numbers aren’t in, but in 2008, fewer than 90,000 people were counted in the metropolitan area; estimates now range as high as 250,000.) All of this goes hand in hand with gambling, and because of this, Sihanoukville has come to be known as the new Macau. In 2018, according to the Phnom Penh Post, the Cambodian government awarded 52 new licenses to casinos throughout Sihanoukville Province, bringing the total to 150. That’s a lot of casinos for this once-sleepy tourist haven.

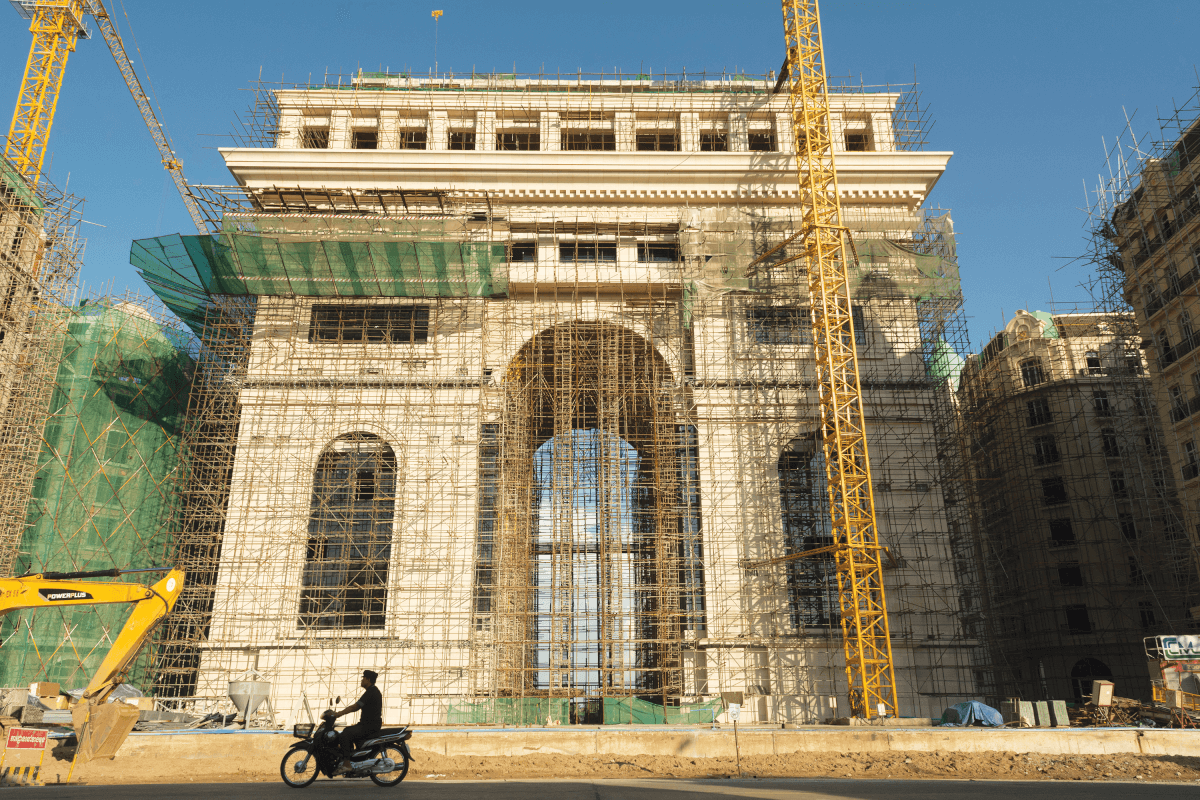

A replica of the Arc de Triomphe on Koh Pich Island in Phnom Penh.

A replica of the Arc de Triomphe on Koh Pich Island in Phnom Penh.

The drive from train station to beach is a swirl of red and yellow luminescence—Chinese shops, Chinese restaurants, Chinese casinos, and groups of Chinese people on the streets, the men in suits and the women in heels that hamper locomotion on a mishmash of sidewalk tiles.

My taxi (a Toyota Camry with the rear end sawed open to hold two facing benches under a tarp) drops me at a spread of concrete bungalows surrounding a pool, across the street from Ochheuteal Beach. The guesthouse sits just before a narrow bridge spanning a mangrove canal, leading toward a forested hill with birds and butterflies. The manager, a European transplant, tells me that hers is one of the last guesthouses remaining on Ochheuteal. Aside from a few adjacent buildings—a small hotel, a sunset lounge—everything else on this beach has been razed.

So things go in Cambodia: when the economy sings, landowners jack up their lease rates, driving out low-end business in favor of high-end clientele. Those who don’t go are typically forced out. The images—well documented during decades of compulsory evictions—aren’t pretty: bulldozers and protests, gunshots and fire. Through blood and tears, flames and ash, Cambodia reshapes itself, again and again.

These expulsions are complicated by the country’s history of war and genocide. Through the years, thousands of residents have fled homes and businesses on land to which they had no legal title. When the Khmer Rouge took control in 1975, they evacuated cities, forcing urbanites to work like slaves in the countryside. Money and possessions were abandoned, as were symbols of wealth, including property titles. By the end of the genocide, nearly a quarter of the population was dead. The rest of the country was degraded, deflated, and displaced. As families regrouped and recovered, millions of people returned to their homes and family lands without proof of ownership. In later years, as the country grew, the rich found ways to dispossess the poor once again.

Here on Ochheuteal, signs of swift departure are all around: cabanas and crab shacks reduced to rubble, scavenging animals, sacks of garbage that bake in the sun and rot in the rain. Sometimes people light trash on fire, stoking flames with metal poles, filling the salty air with an acrid funk.

A few lots down the street, palm trees poke through the shell of a former beachside shop—only its foundation of wooden poles remains, forming a picture frame of the sea beyond. Chairs and mattresses sit in unkempt lots overrun with weeds. I walk through the remnants of a building crushed to the ground, nothing left but the bathroom walls, some PVC pipe, and a concrete floor covered in broken tiles. Up and down the street, everywhere, everything is broken: businesses, homes, lives, as if a tornado had twisted through. But really, the storm was Chinese money.

Somehow, so far, my guesthouse proprietor has stuck it out. She tells me about the other side of the hill, across the bridge and through the woods, where workers are building a mini-city of housing blocks that she says will accommodate 60,000 Chinese – “Sixty thousand!” she exclaims. Could a single complex even hold that many people, the rough equivalent of Rapid City, South Dakota? I’m not sure.

I hire a tuk-tuk driver named Piseth to take me over the hill, but his engine is too weak to make the steep climb. Instead, we take the long way, back through the city, where Bentleys, Porsches, and a muddy Ferrari are parked in front of casinos. We pass entire city blocks walled off in sheet-metal fencing with painted ads: “Rent 1$ Each one Everyday.” Farther on is a billboard in Khmer, English, and Chinese, advertising pile-driving services. And then, from a distant vantage, we see giant skeletons of concrete and rebar beneath construction cranes backed by rolling green hills and blue seas. The buildings-to-be are at least seven stories high and growing. As we get closer, we find one complex after another, some of them guarded by soldiers. Everything that had been there—budget hotels, beachwear shops, and seafood huts where tourists had thronged just months before—was gone. (Later, I checked Google’s satellite view and counted 40 buildings, plus pilings driven for at least two more.)

Elsewhere in Sihanoukville, I watch the owners of a guesthouse selling everything they have. Every mattress, pillow, soup spoon, and coffee cup has to go. Every refrigerator, air conditioner, toilet, and TV remote. Two men leave with a cart of plastic bathroom doors. Others haul away wheelbarrows full of dinner plates. A guy behind the counter relates a familiar story: a Chinese business bought the lease.

My husband takes photos at a nearby construction site, a high-rise in the making. He talks to a worker from Kampong Chhnang, a province a couple hundred miles away. He’s here for the work. He gets $10 a day. It’s good, he says. His boss is Chinese.

Cambodian workers leaving a construction site

Cambodian workers leaving a construction site

The BRI began in 2013, when Chinese President Xi Jinping announced plans to rebuild the Silk Road, the ancient caravan route that spurred trade among Asia, Africa, and Europe. This time, China envisions something even bigger. The BRI will likely cost up to $8 trillion and involve construction projects and investments in at least 150 countries and organizations across much of the world.

In April, when world dignitaries met in Beijing for the Second Belt and Road Forum, Xi Jinping announced a “blueprint of cooperation” that encompassed far more than infrastructure—a global “flow of goods, capital, technology, and people” to spur economic growth and enhance global governance. Although some observers see the BRI as a scheme to boost the Chinese economy, others view it as an effort to kick the United States off its superpower perch.

Already the BRI is changing every place it touches. Analysts note widespread corruption, the potential for irreversible environmental degradation, and fears of debt traps that threaten the sovereignty and self-reliance of poorer countries—all issues that Xi Jinping addressed head-on in his April summit speech, calling for transparency and “green and clean cooperation.” No matter how it all plays out, the BRI will change the pace of life in economies and environments accustomed to slower, quieter ways. New jobs are good; it’s the side effects of big business that cause local communities to cringe.

Sihanoukville has a well-placed deep-water port as well as those tropical beaches; it also has inland links, which are about to get better, faster, and wider: in late 2017, Chinese companies pledged $7 billion in new projects, including an expressway connecting Sihanoukville with Phnom Penh. The existing highway was built by the United States in the 1960s.

Chinese investment has led to a spike in Cambodia’s Chinese population that has sparked tensions. Local news is rife with reports of gangsters, bar fights, car crashes, drugs, and guns—often involving Chinese. Drunk driving, too. The owner of my guesthouse shows me her foot, misshapen from a traffic accident that she blames on an intoxicated Chinese driver.

The troubles extend beyond Sihanoukville. In June 2018, nine people were injured in a brawl between security guards and a group of Chinese in a wealthy new development known as Koh Pich (“Diamond Island”). As I cross the country, I hear the same skeptical assessments of swift change: new money, fast cars, and lots of Chinese bringing lots of problems.

Phnom Penh used to be the “Pearl of South East Asia,” a low-lying capital at the confluence of the Tonle Sap, Bassac, and Mekong rivers. For decades, the spires atop the Royal Palace dominated the skyline. But a new blueprint has emerged. Forty-story towers now loom large over the city’s golden wats, and the proposed TBR Twin Tower World Trade Centre, a joint venture between a Macau-owned contractor and a company founded by the late, notorious Cambodian tycoon Teng Bunma, would, at 133 stories, be Southeast Asia’s tallest building.

One afternoon, I visit the Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts to interview archaeologists for a story about ancient sites. But my thoughts of antiquity are quickly overridden by the sharp and grinding cacophony of construction tools. The archaeologists’ office building is dwarfed by a high-rise going up only a few feet away. It is so close and so tall that I have to crane my neck to see its top. High in the sky are unfinished floors where workers have strung hammocks beneath mosquito nets, making themselves at home in the open air. They work round-the-clock, the archaeologists say. Sometimes glass and bricks fall from above, damaging cars parked in the lot below. A Chinese company pays for the repairs and keeps on working.

In the early mornings, before the heat takes hold, I run along the Tonle Sap toward Koh Pich, a mini-metropolis marketed toward foreign investment. If you squint, the architecture reminds you of Paris, if Paris were new, on steroids, and Chinese. It includes a sprawl of condos, strip malls, and carnival rides among outdoor cafés, plus a replica of the French Riviera. In 2016, the island hosted the annual KARA Cup motorbike race, which also featured young Cambodians gingerly steering a Lamborghini and a Mercedes SLR McLaren around a makeshift course delineated by stacks of tires.

The entire island is managed by a conglomerate called the Overseas Cambodia Investment Corporation (OCIC). Years ago, Koh Pich and the neighborhoods around it were little more than bogs and reeds, the muddy home of many of the city’s poorest residents. They had settled there as refugees in the aftermath of civil war, living in small, simple houses of wood and metal. They sold vegetables and fish on the local streets. And, many still say, they were happy.

But things began to change in the early 2000s, when the Cambodian government partnered with OCIC to develop Koh Pich. The initial visions of massive transformation lined up well with the ideals of the future BRI. Over the course of a few years, residents were evicted and shuttled out of Phnom Penh to new satellite cities carved from rice fields 10 to 20 miles away—far from jobs and, at the time, far from anything city dwellers needed in order to live. Some of the residents took buyouts at well below market rates. Others resisted until their neighborhoods burned. The government blamed accidental wintertime fires, but eyewitnesses reported men throwing fire bombs into homes.

This happened not only in Koh Pich but in almost any poor neighborhood that impeded the dreams of the rich in an age of soaring property values. I lived in Phnom Penh during some of the eviction fires, which destroyed what the government viewed as “squatter camps” and “slums.” According to Amnesty International, 11,000 people were forcibly evicted from their Phnom Penh homes between 1998 and 2003; more than 30,000 were removed in subsequent years. The result was a city prepped for a facelift.

Thaech Phol, proprietor of a noodle shop and restaurant in Phnom Penh. Her clientele is made up largely of families that have been evicted.

Thaech Phol, proprietor of a noodle shop and restaurant in Phnom Penh. Her clientele is made up largely of families that have been evicted.

I visited some of the first satellite cities where the government settled evictees, and I’ve returned several times since. Now, I travel to a place called Sen Sok to see if I can find anyone who recalls Koh Pich before it rose high into the sky. I meet a woman named Thaech Phol and her husband, Thach Sung, who were born in an area of southern Vietnam known as Kampuchea Krom (centuries ago, it was the southernmost stretch of the Khmer Empire). From 1989 to 2002, they lived near Koh Pich, selling seafood. They had a two-story concrete house, a place they loved. But they never had title to their land. Then, Thach Sung says, “The government burned our house.” So they were moved to this village when it was just emerging.

Nowadays, Thach Sung runs a barbershop and Thaech Phol runs a café—husband-and-wife businesses, side-by-side in shared space. Lunch hour starts, and she whips up bowls of noodle soup and plates of pork on rice, served with glasses of iced coffee drizzled with condensed milk. She recalls those early years after losing their house. “I was worried and angry,” she says, though things are better now.

Thach Sung still worries, though, “because the land around here now is more expensive,” he says. “The government always looks—if the land is expensive, they tell people to go away.”

I order soup and drink a glass of sweet, cold coffee, then head around the block. There, I meet a woman named Soeun Theun who sells toilet paper, shampoo, toothpaste, and drinks from a little stall on a dirt path that floods in the rain. She tells me she used to live in a two-story house on Koh Pich but had no documents and was forced to leave. Her home now—a modest, spotless sheet-metal room with concrete floor and outdoor bathroom—is far from any possibility of a better job. “I don’t like it here,” she says, but her reason for staying is simple: “No choice.”

It just so happened that Soeun Theun had an opportunity to see Phnom Penh the next day. A community leader organized a group trip to the city, less than 10 miles away, where Soeun Theun hoped to get a glimpse of her old neighborhood for the first time in years. I later heard about her trip, via text, with help from her daughter. The caravan didn’t make it to where Soeun Theun used to live, but she got a good look at the city and was pleased with how Phnom Penh appears these days. “I wish that we could have a nice house on our own land someday,” she texted, “so that we won’t worry about anything.”

What Soeun Theun saw was the reflection of wealth she doesn’t have, and an economic class to which she will likely never belong. But she also saw the power of money and evidence of China’s economic might. And maybe, one day, some of that largesse could flow down to her—and change everything.