Capital of Willows

On a trip to North Korea, a writer remembers his troubled father, a victim of the “Forgotten War”

Rising above Pyongyang’s low skyline is the Ryugyong Hotel, which recalls the city’s ancient name, meaning “Capital of Willows.” Construction began in the late ’80s but came to a halt in 1992, as the North entered its post-Soviet famine years. The pyramid-shaped “Hotel of Doom,” as Western journalists call it, is sheathed in glass, but its interior remains largely empty and unfinished. As much as Pyongyang’s other landmarks, like the flame-topped Juche Tower or the huge bronze statues of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, before which onlookers are asked to bow and leave flowers in respect, the Ryugyong marks the city’s hallucinatory core.

An American friend and I had entered North Korea through Shenyang, China, a fast-growing provincial capital about five hours by high-speed train from Beijing. We were participating in a weeklong tour timed to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the 1953 armistice that paused, but did not formally end, the Korean War. As Americans, we were prohibited from entering North Korea by train. Instead, we boarded an Air Koryo flight from Shenyang’s modern airport and less than an hour later, after a quick drink service, arrived in North Korea’s capital, where we would meet the other members of our Canadian-led tour group.

Taxiing past decrepit Russian transports, some concealed under camouflage tarps, with solitary farmers and oxen visible beyond the concertina wire, we felt more like we’d passed back in time than across space. Also pulling up to the Pyongyang terminal was a flight from Vladivostok, and soon passengers from both planes were making their way through the crowded arrivals hall. A young woman in a neat blazer and skirt greeted us. “Please,” she said, bowing, “my name is very long. You can please call me Miss Cho.” The young man next to her introduced himself as Mr. Paek but said little else. Outside, in light rain, a driver stood smoking a cigarette next to an immaculate bus.

It was evening by the time we reached our own hotel, the Chongnyon, its exterior closer to a ’70s airport Marriott than the Ryugyong’s hollow futurism. The sky was overcast, the willow-lined Taedong River obscured by fog. We ate dinner in a cavernous dining room, empty but for us and a small army of waitresses in traditional dress. Afterward, we sat with our guides in the hotel’s marble lobby as they laid out the ground rules of our stay—among them, that we must be accompanied by our Korean hosts at all times. Reluctantly, Mr. Paek agreed to take us on a brief walk. The fog had reached a noir-like density, with Kwangbok Street dimly illumined by the blue coronas of streetlights. Streetcars rattled past, and at each stop men and women clustered, talking softly. With Mr. Paek at a respectful distance, my American companion repeatedly leaned close to comment on the otherworldliness of our surroundings. For him, it was as if we’d landed not in a real place but in a timeless elsewhere, a past both captive and free to be whatever we wished it to be. In fact, aside from its relative quiet and dark, the city was completely ordinary, which is to say it was nothing but itself. There was a low hum of conversation. There were small restaurants on the ground floors of the concrete apartment buildings, separated by long stretches of empty land, an outdoor café with plastic tables and chairs, all the things that to my companion, raised in a suburb of St. Louis, were screens on which to project his expectations of the Hermit Kingdom.

Forget everything, I wanted to say to him, and just take it all in. But then, memory loss—or better, memory’s presence in the form of stories left untold—is the Korean War’s primary legacy. Gradually, as he kept talking, insisting on the strangeness of the ordinary, my friend finally seemed to recognize his preexisting notion of Pyongyang as a hallucination, something he’d carried with him from the American heartland. He grew quiet, stunned into silence by the sound of his own voice.

From a North Korean bunker, I could see far across the Demilitarized Zone, an internal border running 150 miles along the 38th parallel, bounded by the China Sea and, to the east, the Sea of Japan. A uniformed officer briefed us on the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War and the DMZ’s importance as a buffer against the “running dogs” of the South. The anniversary of the armistice, much heralded by the North Korean government, was just two days away. In the United States, it would pass almost unnoticed.

[adblock-right-01]

The officer led us out to a platform, where we could freely photograph the far side of the line. Earlier that day, we’d visited Panmunjom, roughly 12 miles to the west, a “peace village” that straddles the DMZ. I had seen it once before, in 2010, from the southern side, exactly 60 years after the start of the war. There, in a simple wooden building, I sat in the seat where, on the morning of July 27, 1953, Lt. Gen. William Harrison Jr., the U.N. Command’s delegate, signed the armistice agreement. But today the main attraction was the “concrete wall,” a barrier the North Korean officer said the South had constructed in violation of the armistice, which prohibits the introduction of permanent obstacles along the line of demarcation. I don’t know for certain that the wall really exists, but in the distance I saw what looked like concrete.

Not far from this bunker, a few weeks before the armistice was signed, my father was wounded by a grenade in the second battle for Pork Chop Hill, named for its shape on topographic maps. He never spoke of the war, but it was everywhere visible in his chronic joblessness, his alcoholism, his volatile temper, the periods he spent in jail, and in a final confrontation during which he held my mother and me at gunpoint with a U.S. Army-issue Colt .45. My mother and I testified against him at trial, where he was sentenced to six months. When he got out, my mother divorced him. I didn’t see him again until the day of my sister’s wedding, a decade later, when he pulled me close in the receiving line and told me he’d had to ask my aunt who that stranger was leading his daughter down the aisle.

The ridges south and east of the bunker dissolved into humid, granular air. Pork Chop might have been visible from there had I known what to look for. The previous autumn, while living for a few months in Berlin, with its own history of division, I first logged on to Google Earth and rode satellite images down to the coordinates provided by the Korean War Project. In 1979, its founder, Hal Barker, began researching the war history of his father, a career Marine Corps pilot, awarded the Silver Star for his attempted helicopter rescue of a downed pilot during the October 1951 Battle of Heartbreak Ridge. Like many other children of Korean War veterans, myself included, Barker knew little about his father’s war experience. As he gathered more material and helped initiate the fraught but ultimately successful effort to establish the Korean War Veterans Memorial on the Washington Mall, he struggled against the persistent amnesia of the “Forgotten War.” What does it mean when someone repeats over and over again that this, right here, is what’s forgotten?

In the quiet of a Berlin apartment, blocks from the old wall, I watched as the Korean peninsula appeared under a red grid provided by the Korean War Project, its midsection dense with yellow pins representing individual battles. From there I searched specifically for Hill 255, Pork Chop’s official military designation, and with a final click, dropped earthward from virtual orbit. At an altitude of 100 miles, the steep mountains and river valleys that cover more than 80 percent of the peninsula resolved into feathery patterns, like ice in formation. My still-invisible target was marked by animated crosshairs, eerily simulating one of the most intense—and entirely one-sided—air campaigns of the 20th century. In April 1951, after President Truman fired Gen. Douglas MacArthur, who had demanded the authority to use atomic bombs on the battlefield, the Joint Chiefs decided that such weapons were pointless, given that conventional bombs had already leveled nearly every standing structure in the North. There were simply no more targets to destroy, but still, the bombing continued, as did practice runs by warhead-laden B-29 Superfortresses flying out of U.S.-occupied Okinawa. This brief war, forgotten though it may be, was exceptional in its ferocity, killing nearly 54,000 U.S. troops and more than two million Koreans, most of them civilians. The devastation remains visible today in the eerie emptiness of Pyongyang, its broad swaths of undeveloped land, and the surreal gesture of the Ryugyong Hotel.

Reaching 10,000 feet, I could see faint lines, the remains of the old battlefront, preserved within the DMZ’s cleaner demarcations. At half that distance, individual structures began to appear—observation posts, bunkers, gun emplacements. Finally, 100 feet from the ground, I swooped off the vertical as if piloting some fantastic aircraft; by this point, the high-resolution satellite images had become pure animation. In a matter of seconds, reversing the hours, days, and years of my father’s long march to a Veterans Administration hospital bed, I had arrived at Pork Chop Hill.

East of my perch in the bunker, brought closer through antique-looking periscopes, the DMZ stretched on in a series of rolling green crests and ridges that, during the war, had been stripped and burned by static trench warfare—a far cry from the clean, swift dream of strategic dominance projected by superior American technology, particularly air power. My father described the landscape in a letter home to his parents in Queens, one of the many that my sister and I found buried in his cluttered house trailer after his death. Dated July 31, 1953, it was his first letter home following the armistice, written only three weeks after he was wounded.

The particular hill that George Company is on is 487 ft. high, affording a splendid view up the Chorwon [sic] Valley and miles to the south toward Seoul. I had lunch on the Hill a couple of days ago and was able to view some very interesting sights. The first was that of dear old Porkchop, which can be seen several miles to the west. It is the first time I have seen it since I left for the hospital. When the American troops withdrew the Air Force came in and turned what was once a green hill into a pile of brown dust, as was the same case with Old Baldy, named for that reason.

Other sights included the appearance of several Chinese on a nearby hill, and the great influx of rear area personnel on sightseeing tours, who viewed the MLR [Main Line of Resistance] for the first time. The night before last I went up on the hill with the mailman. This was a most enjoyable ride as we had an open jeep to ourselves and were able to take our time. Our first stop was the CP on top of the hill where we left the bulk of the mail. From this lofty vantage point we were immediately struck with the contrast to pre-truce sights. Before the ceasefire it was blacked-out in the valley and spooky too. The only lights were moon-beam Charlie (the 3 or 4 mammoth searchlights that sweep the valley), bursting shells on Chinese hills, and the resulting fires, flares, or tracers from our .50 calibers.

Now there are lights all over everywhere: bonfires, vehicles, and others. The road back to rear looks like a parkway with all the lights of visiting traffic. Two of the big searchlights are placed on the hill with my company and they were lit also. They are about 5 or 6 feet in diameter and cast an appreciable beam for miles.

The story forms a progressive arc from darkness into light. But hidden from that illumination, still embedded in my father’s body, was the shrapnel that had wounded him, lodged too close to his jugular and esophagus to be removed. Eventually, as the extent of his internal injuries became clear, he was evacuated through Japan to San Francisco. But the body bears more than external scars. Much has been written lately about posttraumatic stress and the immediate challenges veterans face as they attempt to reenter civilian life. Far less acknowledged, though, are combat’s long-term effects on veterans and their families. As vets age, the physical and mental experience of combat is transformed—not lost, but distributed through tissue, along neural networks, recycled through a body’s changing landscape.

The hills, once churned to brown dust by high explosives, today are covered with foliage, the DMZ a suture between two different worlds. But the scars remain. Fragments of the war—destroyed tanks, unexploded mines, spent shell casings—still surface there, just as, over the decades, tiny slivers of metal rose through my father’s skin. Stretching along the far side of the line, opposite the North Korean bunker in which I now stood, was the Cheorwon Valley, where American and U.N. troops, my father among them, were sent forward into combat. The Japanese, who occupied Korea and neighboring Manchuria from 1910 until 1945, had built a silk mill there, along the old Seoul-Wonsan railway line, turning many local farmers into industrial workers. Today, it is a relic of earlier times, lost in the DMZ. The mill, writes South Korean photographer and peace activist Lee Si-Woo, “which had once been filled with dreams of liberation, fell into ruins and only lends its ears to the songs of the passing wind. A flock of gray cranes descends on the beautiful swamp near the minefield by the ruined silk mill walls along which workers used to walk on their way to and from work. The cranes fold their wings as if sweeping the empty space downward, and then walk along the wall, as if they are savoring something. Their feathers are the same colors as the workers’ garb.”

Shortly after he returned from Korea, convalescing in his parents’ apartment in Queens, my father began keeping a journal, a typescript of which I found with his letters home. The last entry is dated a few months before my parents met in Vermont, where my father was working as a reporter for the Burlington Free Press.

On June 17, 1961, almost exactly eight years after he was wounded, my father wrote,

I haven’t had a gun since I was in the army but today I acquired one. A friend of mine here in town showed me one of these automatics that he had and so I decided to get it from him. This I did by trading three small rugs for his bare room and an Italian wine bottle for his bare mantelpiece.

The gun: he showed me all about it and gave me a quantity of shells. Then I left him and drove to Worcester where I went out on a country road and found an isolated place in the woods. Here I set up a target, loaded up and fired off all but enough cartridges to fill the clip and have one in the chamber. I hit the target enough times and at a good enough range to satisfy me of this weapon’s usefulness, should the need ever arise.

This gun is a fantastic thing. It has absorbed my attention and has a very domineering personality all its own. I feel its presence, I am completely conscious of its own power: it is a sinister thing. It is a living thing. I don’t make it do what it does. It does what it does of its own accord and so has to be looked out for. It’s really extraordinary. I know eventually I will become used to having it around and in time it may even become inanimate. I don’t expect ever to use it, except perhaps occasionally to test fire it and then clean it out again. No one will ever know I have it except its former owner whom I have sworn to silence and to forget the whole transaction. If I ever become intimate with a woman and she lives with me I will tell her about it and teach her how to operate it. But other than that, once its influence has worn off, it will be consigned to silence between the mattresses.

Should the need ever arise. This was the same weapon my mother and I would face, separated by the space of a room and the duration of a heartbeat as the barrel swung between us. I found it where he had hidden it before the deputies took him away, handcuffed and swearing. The magazine held a single round.

Perhaps it’s merely coincidence, but two months before my father acquired the pistol, on April 28, 1961, he wrote for the first and only time about how he was wounded. In contrast to his growing sense of alienation and anxiety, from which his handgun seemed to provide some relief, “when I was in Korea as a soldier on the front line,” he wrote, “I was completely at ease with myself. The Chinese daily shelled our positions—or I should say day and night. And men were being killed all around me, not so many as to be tripping over bodies or anything, but if one were not killed in the immediate unit it would be somewhere down the line in a skirmish which would graduate itself as the tale was passed along.”

The chain of command broke down almost immediately under the initial Chinese assault, my father writes, and he and the rest of the men

were completely without leadership and didn’t have the foggiest of what was going on—whether we were still attacking (for we had already gained the hill, or what we knew of it, and saw no aggressors) or if we were now defending, momentarily expecting the Chinese to return up the side of the hill that fell away in front of us. We [my father, who was a machine-gunner, and his assistant] set the gun up at the open end of a partially broken down bunker-type trench and, facing the enemy position, now in sight, commenced firing up a trough in the terrain in a grazing fire, the advantage of which I don’t think we clearly thought about or cared about—it was negligible. But as long as we were doing something, we felt relative ease of mind in our growing apprehension. The tunnel-like trench was crowded with men who were mostly doing nothing.

I didn’t know what we were supposed to be doing. Then our leadership arrived.

First from behind I heard the hoarse shout of our sergeant yelling for us not to burn the barrel of the gun up with our rapid, continuous firing. When I looked around I saw him lying on the floor of the trench with men working over him. He appeared to have most of his legs chopped off. Then one of the lieutenants arrived. He told us to take the machine gun out into the open, to some vague point, and set it up where it would assist in the attack. I didn’t quite know what attack he was talking about because everyone else was standing around in the trench. At any rate I stumbled out of the relative shelter of the trench and ran about ten yards up the center of the trough where we set up again. I was aware of the lieutenant yelling behind us and I was equally aware that he wanted and expected us to climb out of the trough up onto the hillside and set up there. The lieutenant remained in the covered trench and attempted to direct the operation from that vantage point. This was the inglorious part of my fighting. I knew that the gun should be on high ground, but as long as the other men and principally the yelling lieutenant chose to remain in the shelter of the bunker-type trench I chose to be damned before I climbed out of the trough onto the exposed high ground.

Well, that’s it as far as the inglorious part of it all went. As it was, a Chinese grenade went off nearby and my assistant disappeared. So did I, for that matter: I dove into a hole, later was wounded by another grenade and for the rest of the time on that hill—until early the next morning when we were taken off—I “cooled it” as the saying went, primarily because I was temporarily and willingly deaf—and from the time of my wound completely disinterested and damned scared.

According to military historian Bill McWilliams, my father’s unit—G Company, 17th Infantry—became pinned down by enemy fire after its counterattack stalled. “George Company lost nearly half its men, killed or wounded,” he writes. “The remainder, bereft of officer and NCO leadership, remained isolated, hugging the safety of battered and collapsed trenches, and a few in bunkers.”

North Korea’s broad and largely empty concrete highways were built to accommodate tanks, not cars. Occasionally, a new SUV or sedan blasted past us, its driver hidden behind tinted windows, leaning impatiently on the horn in spite of all that space. More numerous were the old Soviet-model trucks that serve as buses, belching smoke from the wood-fired furnaces in their beds. Far from anywhere, people moved alone or in groups along the shoulder, walking or riding bicycles. Rain gleamed on the concrete, and the mountain valleys were filled with mist.

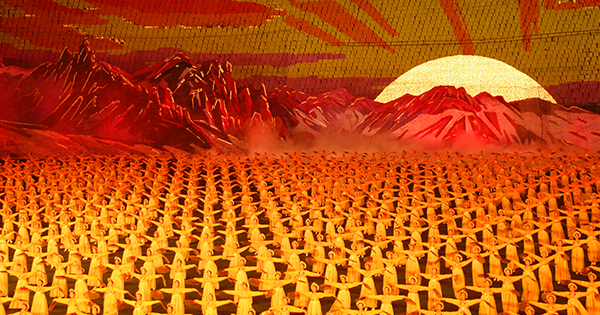

On the evening before we left Pyongyang for Kaesong and the DMZ, we had attended the annual Arirang Mass Games, a spectacular, masterfully choreographed tribute to the Fatherland’s rise and triumph. Now we had returned to the capital for the anniversary of the armistice, which was to be commemorated by a massive military parade, presided over by the new Great Leader, Kim Jong-un. A few Westerners and thousands of excited North Koreans lined one of the avenues leading out of Kim Il-sung Square. Trucks and troop carriers full of soldiers sped past, along with tanks, missile launchers, and massive artillery pieces. Many of the soldiers wore on their chests the so-called nuclear backpacks that would get so much attention in the Western press, which were in fact flimsy nylon, like those carried by schoolchildren, and marked with a large Hazmat symbol. They supposedly contained protective gear for use in the event of fallout from an American nuclear attack, but more likely they were empty. The cheering crowd pressed against the white-uniformed policewomen who lined the avenue and tossed bouquets of fake flowers at the passing troops.

Such things appear crazed or coerced on Western television, as does the mad pageantry of the Mass Games, but whatever the deeper pathologies at work, the excitement we witnessed was genuine. For the young soldiers, our Canadian tour leader told us, this was due primarily to their being permitted to visit the capital city for the first and perhaps only time in their lives. The same nationalist enthusiasm is everywhere on display in Pyongyang—from the mausoleum containing the embalmed bodies of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il to the recently renovated Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, filled with giggling schoolchildren and aging Chinese veterans, to the USS Pueblo, a captured American spy ship on display in a tributary of the Taedong River. Yes, patriotism is necessary for survival in the North, but there’s an authentic sense of pride in it, as well—and a visceral memory among the people of the costs of war.

From Pyongyang, we ventured northeast to Hungnam, the port city from which American and U.N. troops, along with Korean civilians, had been evacuated after Chinese “volunteers” entered the war in December 1950. Twenty-five kilometers to the northwest is the city of Hamheung, almost completely destroyed in the fighting and rebuilt by East German engineers in the ’50s and early ’60s. During the famine years of the ’90s, Hamheung suffered badly, especially its children, sparking a short-lived insurrection by groups of North Korean soldiers, who marched on the capital only to be gunned down or imprisoned. Nearby is Re-education Camp No. 9, a detention facility for political prisoners noted for its brutal conditions and high mortality rate. At a collective farm outside the city, we saw mothballed Soviet tractors, each one displayed together with a list of the record crop yields it brought in. The collective’s model store was stocked with brightly colored consumer goods, produced in local factories: bolts of fabric, children’s toys, shoes, kitchen utensils, and dried food. None of it was for sale.

[adblock-left-01]

On the beach outside Hungnam, we body surfed and danced on the sand at a family barbecue. Mr. Paek and I waded in the Sea of Japan and drank warm beer. I talked about the urban community college where I teach, on Brooklyn’s southernmost waterfront, about the struggle to keep education accessible for students increasingly trapped in a downward spiral of earning potential and debt. In my classes, I have young people right out of high school, adults returning in middle age, first-generation immigrants from every corner of the world, the children and grandchildren of immigrants, veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, ex-cons, and retirees. Mr. Paek seemed most amazed by those who, after a lifetime of work, would return at no cost to take classes.

“They cannot do that here?” I asked.

“Why would they?” he replied, dismissively. This was but one of many conversations I had with him, during which I learned little about his life except that he’d attended university in Pyongyang for foreign studies and languages, that his father was a government official, his mother a housewife, and that he and his sister still, in their early 30s, lived at home. Openly derisive, he thought all universities in the United States were reserved for a tiny elect. It was difficult to argue with him. From either side of the divide, all we see is a cartoon, stripped of nuance, of history.

The late French filmmaker Chris Marker, in an essay accompanying a 1959 book of photographs he took in war-devastated North Korea, wrote that in Korean folk wisdom, eating the flesh of birds will weaken the memory. And without memory, it becomes impossible to tell stories, and stories, if not told, will rot and give rise to terrible dreams. There is one man, Marker tells us, who “closed up all his stories in a sack—they took revenge, became poison fruits, scalding water, red-hot iron, a tangle of snakes. They had to be killed with swords.” Reading this, I thought of the hollow concrete walls of factories in the Cheorwon Valley, abandoned railway lines, cranes with feathers the color of a worker’s uniform.

Later, I asked our Canadian tour leader about who Mr. Paek really was, since it was Miss Cho who did all the daily translation, pointing out what to look at, explaining what we could and could not do.

“He could be security,” the Canadian said. “Or maybe he’s just quiet.”

The Ryugyong Tower remained visible long after we left the city for the airport. After I said goodbye and passed through the security checkpoint, Mr. Paek stood watching. I faced him from a place he could not go, the portraits of Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il smiling over his shoulder. He bowed deeply, holding the position for a long time. Glancing away quickly at the list of departure destinations, seeing only Shenyang and Vladivostok, I turned back, but he was gone.