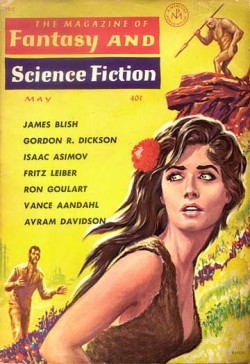

The other day, while roaming through the book-sale room at a local library, I spotted eight or nine issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. All of them were from the early 1960s, with the muted, matte covers of that era, most of them with illustrations by the late Ed Emsh (whose wife, Carol Emshwiller, is one of the greatest living writers of fantasy and sf). Each digest originally cost 40 cents, but now—50 years later—they were only a quarter apiece, and I bought them all.

The other day, while roaming through the book-sale room at a local library, I spotted eight or nine issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. All of them were from the early 1960s, with the muted, matte covers of that era, most of them with illustrations by the late Ed Emsh (whose wife, Carol Emshwiller, is one of the greatest living writers of fantasy and sf). Each digest originally cost 40 cents, but now—50 years later—they were only a quarter apiece, and I bought them all.

For me, such magazines resemble Proust’s madeleines: they are vehicles of sweet memory, bibliophilic time machines. An old joke goes: What is the golden age of science fiction? Answer: 12. Back in 1960, when the earliest of these newly acquired issues of F&SF first appeared, I would have been 12.

The early 1960s weren’t just the heyday of science fiction digests. Corner drugstore racks were crowded with weekly or monthly issues of Life, True, Mad, 16, The Saturday Review, The Saturday Evening Post, Modern Romance, True Confessions, Reader’s Digest, Popular Mechanics, and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, among many others. People read a lot of periodicals in those days. Not anymore. For genre fiction these are especially tough times, even though the short story has always been its best showcase.

Presented for your consideration, as Rod Serling used to say in his introduction to that era’s The Twilight Zone, these eight issues of F&SF. I count at least four modern classics: Theodore Sturgeon’s novella “When You Care, When You Love,” Avram Davidson’s “The Sources of the Nile,” Ray Bradbury’s “Death and the Maiden,” and Joanna Russ’s “My Dear Emily.” The incomparable John Collier—best known for his collection Fancies and Goodnights, currently available as a New York Review Books paperback—is represented by a novelette “Man Overboard” and Robert Sheckley—whose funniest and most imaginative stories are also available in a volume from NYRB—contributes “The Girls and Nugent Miller.”

There are also science articles by Dr. Isaac Asimov, book reviews from Damon Knight and Alfred Bester (author of that most seminal of modern sf novels, The Stars My Destination), even some examples of light verse by Brian Aldiss, not to overlook the silly punning stories of “Ferdinand Feghoot.” Yet there are lots of real surprises here too. In the September 1960 issue appears “Goodbye,” described as the first published story of Burton Raffel. Raffel would make his name not as a pulp fictioneer but as one of the most versatile and admired translators in the world, with a special interest in epic works such as The Nibelungenlied, The Divine Comedy, and Don Quixote.

In other issues I find a reprint of Truman Capote’s “Master Misery,” stories by such largely mainstream authors as George P. Elliott, Howard Fast, and Bruce Jay Friedman, and even an early work by one of my favorite people, that luminary of Wesleyan University, Kit Reed. Given a weekend at the beach, with no looming deadlines, I could be quite happy with my two dollars worth of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction.

After all, even the classified ads are redolent of my lost youth. “Develop a powerful mind while asleep. Also, reduce tension, stop smoking, lose weight without drugs. Clinical tests 92% effective. Join International Research group … details free.” Now what could this be? A come-on for Dianetics? A course in self-induced hypnotism? There’s no way to know, except to write in for those free details. Another ad advertises “rocket fuel chemicals” and still another “Birth Control, 34 methods explained”—and not only explained: “Illustrated. $2.98.”

The back covers of several issues carry endorsements of the magazine’s quality from such literary eminences of the day as Clifton Fadiman and Orville Prescott, not to mention Hugo Gernsback (after whom a famous sf award, the Hugo, is named). Even Louis Armstrong turns out to be a fan: “I believe The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction appeals to me because in it one finds refuge and release from everyday life.” Unfortunately, the great jazzman goes on: “We are all little children at heart and find comfort in a dream world, and these episodes in the magazine encourage our building castles in space.” I don’t think any modern sf writers or readers would agree with those saccharine sentiments. And yet, what I’m describing here is exactly that: the comfort found in a dream world.

Today The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction is edited by my friend Gordon Van Gelder—and it’s still great. You should try an issue. As it happens, I will be picking up a few more golden-age digests this weekend, at Capclave, the local Washington D.C. science fiction convention, where—as its motto proclaims—“reading is not extinct.”

But let me end with a story. A few years ago Elaine Showalter, long a distinguished professor of English at Princeton, retired to Washington. One afternoon we had lunch in Bethesda, and somehow science fiction came up in the conversation. Laughingly, she said that she once taught a student who told her that the dream of his life was to become the editor of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. She couldn’t quite place his name. I quietly said, “Was it, by chance, Gordon Van Gelder?” With a look of astonishment, she said, “Why, yes. How did you know?” When I told her that Gordon had, in fact, become editor of F&SF, she said, and I agreed, “How wonderful to be able to realize the dream of one’s life.” Happily, some dreams turn out to be more than just castles in space.