Sometime in early March the news reached me, as news does, passed from one person to another, growing and changing, sometimes elaborated upon, sometimes curtailed, sometimes whispered, sometimes shouted as it moves down the chain of transmission. This news was of a kindergarten in Madrid, closed due to the coronavirus scare. In Spain, no one thought much about the virus before March. No one worried. No one I knew.

Not a scare, I reminded myself, at least not just a scare. Not simply exaggerated alarm, but justified alarm. Even before any deaths, alarm at contagion is reasonable. More than reasonable—almost demanded. David Sedaris, more than a dozen years ago, was warned off theater seats, hotel bedspreads, and shopping cart handles at the grocery store. “The germs,” his sister confided when he asked why she was pushing the cart with her forearms. I laughed when I first read the essay a decade ago. It seemed eccentric, that kind of worry, though I’d known people just like that—a college friend who became a physician and was squeamish about germs though not about cutting up bodies, and her grandmother who was incensed at anyone sneezing in the cinema. Maybe it was funny because I’d known people like that. As if germs could be avoided! As if worrying did any good!

But the closer the virus outbreaks grew, the more inclined I was to wipe off my face the silly smile from thinking about Sedaris’s sister. Taking precautions—that was nothing to laugh at, not anymore. Only, I couldn’t wipe the smile off—no touching our faces! We knew very little about the virus, but we knew that. So I stared in perplexity at an eight-year-old one afternoon back in March, just before across-the-board school closings in Spain. She stepped up to me at the beginning of class and lifted her face. “Look,” she said in Spanish pushing out her lips.

“What?” I asked, in English.

She put a finger to her upper lip to show me a tiny flap of peeling skin there. “Ah,” I said.

“Can you get it off?” she asked.

Even without the coronavirus I couldn’t go putting my fingers on a student’s mouth. “I don’t think so,” I told her. She pouted and waited.

“Try this,” I said, demonstrating how to scrape her bottom teeth against her top lip. She tried, but without dislodging the piece of skin. I sent her back to her seat to keep trying. She immediately turned to the boy next to her to get him scraping his lip too.

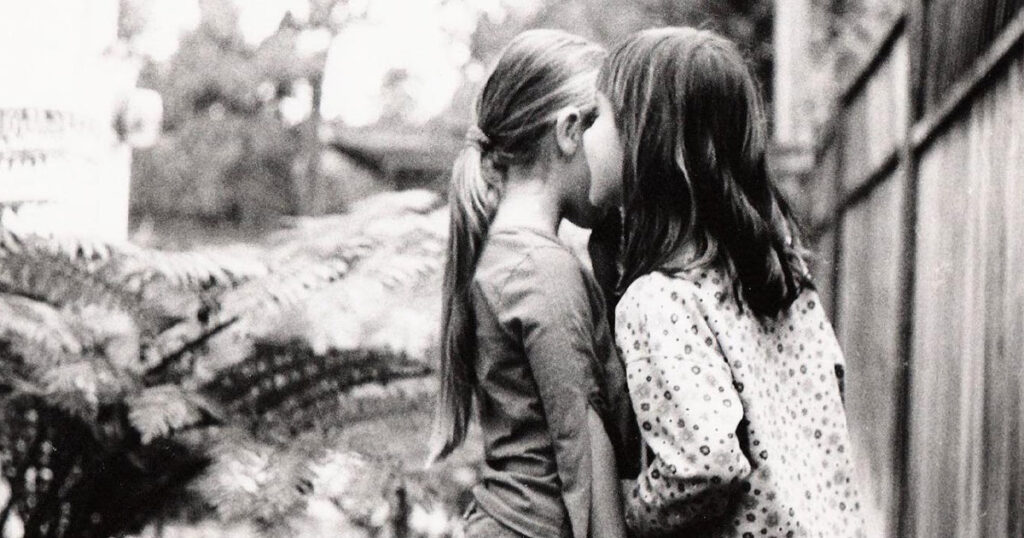

That day the children were particularly antsy, especially loud, and quite heedless of my instructions. The activities were a flop, the workbook exercises hardly better. I gave up and put a song on for them to sing along with, but they merely talked louder. Long before the last 10 minutes, I was ready for a game to restore order and put us in a happy mood. Simon says is a favorite, but I imagined how that would play out with the unit’s vocabulary: Simon says touch your face! Or hair, or eyes, or teeth, or mouth. Chinese whispers was just as problematic, with a child drawing close to whisper into another’s ear, and that child echoing the message to the next, around the classroom. I grew up calling the game telephone. It can be quite funny, but it wouldn’t do. I needed another, but couldn’t think, with the clamor in the classroom. As I sat there at my desk, overcome by the noise and energy, a student, a different girl, edged in to report that the boy next to her hadn’t even started his workbook exercise. She spoke in a fierce whisper, getting so close she was nearly sitting on my lap.

She is a serious student, a thin, pretty girl with dark eyes, long wavy hair, a spot of color in each cheek, and a reflexive grimace, as if always just surprised by something mildly shocking. She’s attentive, following my lead, frowning when I frown, lively only if I am, disapproving of her classmates’ antics, worrying for my sake. And now here she was, angry that her classmates were showing such unbounded excitement. “Look at them,” she said in Spanish, and she shook her head, in real distress.

“Shall we play a game?” I asked her.

She pursed her lips and replied that she didn’t think that would work.

“Let’s try.”

But she was right. The announcement of a game, which usually cuts the noise in half as the children put their colors away and hand in their workbooks, had no effect whatsoever. My student and I watched the other six kids continue in the same trajectory toward a pinnacle of noise and excitement. That afternoon, four days before the confinement, they seemed as unstoppable as a runaway stagecoach, horses snorting and stomping. Seven weeks of house confinement awaited those children, seven weeks of never stepping onto the street, or running through a park, or feeling a breeze or even the sun, except for what filtered in through a window. What would that be like?

At the end of April, those children were let out for the first time in those seven weeks. An hour a day is what they got. Other children might have made a mad rush into the street, but I could imagine the serious little girl frowning as she tentatively put her toe to solid ground, wondering whether it would hold.

With the releasing of the children, the worst was over. Or so we were told. Of course, we had also been told all along that children were not at risk, though obviously all along something was in the air, something catching. In my classroom on that March afternoon, the only one not already infected by the general excitement and hysteria was my small enforcer, standing at my side. Some other bug had bitten her. “Look at them,” she said.

I did. They needed an outlet. But she needed a purpose. What could it be? Not to whip the others into shape—she was too delicate for that, and her voice liable to turn peevish. I shrugged at her, and she shrugged back. I looked thoughtful, and so did she. I raised my eyebrows, and hers rose. Worrying might actually do some good—the confinement saved thousands of lives, it’s been reported—but worrying did her no good. I smiled, a big smile, lopsided and foolish, kind of goofy, but a fine smile, as I saw when it came echoing back.