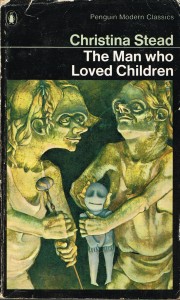

Long before I even saw Washington D.C., Georgetown, R Street NW, or 34th Street NW, I caught glimpses of them in Christina Stead’s The Man Who Loved Children (1940). Alongside Sam and Henny Pollitt’s progeny, I looked down on the steaming summer city and across to the Virginia highlands. When the family moved to Annapolis, I helped renovate their slum of a house. Anchorage, attachment: in the beginning, for me, was the place.

Yet, though place helps to elaborate the scope of this extraordinary novel, as do deftly inked-in treatments of social, economic, and historical contexts (the action takes place in the late 1930s), its true epic character derives from the spaces within. The depth and range of its portrait of a hopeless marriage—the parents’ madness and badness, their six children’s innocent den-life amid the ruins—are not just masterly in their vivid delineation and unsparing psychology; they also show how frail human institutions are, especially commonplace, keystone ones. This novel is a critical work, with a strong satiric strain and the satirist’s disgust and sense of the grotesque. Down with sentimentality! Light, yes; sweetness, no—that was how words should work, I thought.

Still, at first the Pollitt parents seemed too monstrous. Self-hating Henny, “beautifully, wholeheartedly vile,” narcissistic Sam “always righteous, faithful, and understanding” (in his own mind), are so inordinate that I could hardly face them, unwilling or perhaps unready, to accept how close extremes are to the surface of circumstance. I didn’t want reminders of the versions of that closeness I’d seen in my own home (that everybody has seen, probably). Where I came from not only elicited fidelity but also became a midden of memory. And memory meant facing, owning up.

Perhaps I would eventually have learned my lesson about memory as a critique of place. But the sheer excessiveness of The Man Who Loved Children brought me into unavoidable collision with them. I had to struggle—that is, to think. It is not a perfect book, but it is a great one.