’Tis the season when choral societies start practicing their “Hallelujahs” and theaters around the country stage A Christmas Carol. Readers have their December traditions too. To my mind there are two kinds of literate diversion particularly appropriate to the weeks just before and after Christmas: either Golden Age mysteries and ghost stories or what one might call “seasonal” poems and stories.

’Tis the season when choral societies start practicing their “Hallelujahs” and theaters around the country stage A Christmas Carol. Readers have their December traditions too. To my mind there are two kinds of literate diversion particularly appropriate to the weeks just before and after Christmas: either Golden Age mysteries and ghost stories or what one might call “seasonal” poems and stories.

Into that first category falls the so-called “Christie for Christmas.” For years, publishers brought out an Agatha Christie whodunit just in time for holiday gift-giving and, one assumes, post-holiday reading. But all sorts of genre writers have traded on the association of Christmas with cozy chills, Dickens being the pioneer and the story of Ebenezer Scrooge remaining the undisputed champion.

Yet there are many other fine, lighthearted Christmasy works, including the wonderful Dingley Dell chapters of Dickens’s own Pickwick Papers, P. G. Wodehouse’s “Jeeves and the Yule-tide Spirit,” Damon Runyon’s “The Three Wise Guys,” and Jean Shepherd’s “In God We Trust: All Others Pay Cash” (the basis for that nostalgia-rich and hilarious film A Christmas Story). To this day I am still moved by those two old-fashioned, sentimental classics, O. Henry’s “The Gift of the Magi” and Henry Van Dyke’s “The Story of the Other Wise Man.” Still, I’d like to recommend three of my particular favorites for the upcoming holidays—a novel, a poem, and a short story.

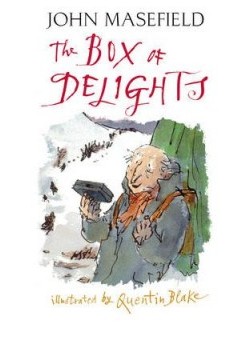

John Masefield’s The Box of Delights begins a few days before Christmas as the English schoolboy Kay Harker is en route to visit his guardian and cousins near the cathedral town of Tatchester. On the train he meets a pair of sinister strangers, has his money stolen, and loses his ticket. When Kay finally reaches his station, he encounters an aged Punch-and-Judy puppeteer, who asks him to perform a small favor:

“Master Harker, there is something that no other soul can do for me but you alone. As you go down toward Seekings, if you would stop at Bob’s shop, as it were to buy muffins now. … Near the door you will see a woman plaided from the cold, wearing a ring of a very strange shape, Master Harker, being like my ring here, of the longways cross of gold and garnets. And she has bright eyes, Master Harker, as bright as mine, which is what few have. If you will step into Bob’s shop to buy muffins now, saying nothing, not even to your good friend, and say to this Lady ‘The Wolves are Running’ then she will know and Others will know; and none will get bit.”

Kay agrees and immediately afterward, in the distant fields, begins to glimpse what look like large Alsatian dogs “trying to catch a difficult scent.” When the old Punch-and-Judy man next reappears, he gives Kay a small box for safekeeping. It is no ordinary box. I will say nothing further except that this terrific children’s fantasy novel reaches its climax during Tatchester Cathedral’s 1,000th Christmas Eve service.

Thomas Hardy’s “The Oxen”—based on a legend that stable animals kneel on Christmas Eve—is short enough to quote here in its entirety. A “barton” is a farmyard, and a “coomb” is a hollow or valley:

The Oxen

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

This poem always brings tears to my eyes.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Blue Carbuncle” opens this way: “I had called upon my friend Sherlock Holmes upon the second morning after Christmas, with the intention of wishing him the compliments of the season.”

Before long, the great detective is dazzling poor old Watson with one of his most astonishing feats of deduction. A possible client has left behind his old hat:

“It is perhaps less suggestive than it might have been,” he remarked, “and yet there are a few inferences which are very distinct, and a few others which represent at least a strong balance of probability. That the man was highly intellectual is of course obvious upon the face of it, and also that he was fairly well-to-do within the last three years, although he has now fallen upon evil days. He had foresight, but has less now than formerly, pointing to a moral retrogression, which, when taken with the decline of his fortunes, seems to indicate some evil influence, probably drink, at work upon him. This may account also for the obvious fact that his wife has ceased to love him.”

With that, Holmes and Watson are off on the case of the stolen Christmas goose. Many Sherlockians reread this story every year, usually on December 27. It is, as Christopher Morley famously declared, “a Christmas story without slush,” and one of the most charming of the adventures of the immortal duo of Baker Street.