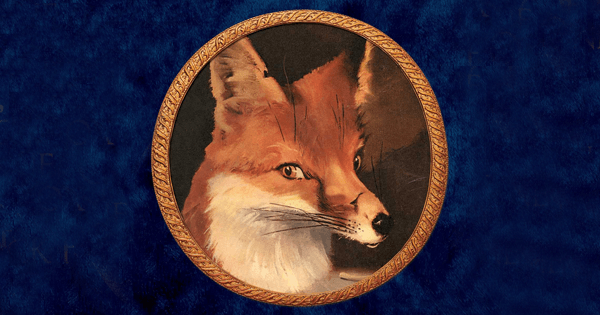

The first book that nailed me, that so absorbed me that I forgot what time it was and where I was and that I was reading a book and not actually inside the book? Easy: Cinnabar, the One O’Clock Fox, by Marguerite Henry, with artwork by Wesley Dennis, which was published the year I was born. I read it about nine years later, at the small wooden library in our small town, and I can still remember the silvery light of a gray afternoon outside the window, and the dignified ancient musty sturdy formal scent of the building, and the loud shimmering silence of the library, and the dawning deliciousness of the feeling that this was the greatest book I had ever read, a greater book than I had known was possible to read, and that I had enough time, while waiting for my older sister to reclaim me from the library, to read the book at least twice, which I did, with increasing awe and wonder and delight. Not only was the text informative about the life and nature and habits and pursuits of red foxes, which are totally cool and wry animals you could spend your whole life studying and never know everything there is to know, but this fox also liked to tease and goof none other than George Washington. Just for fun, Cinnabar shows up every day at one o’clock in the afternoon to lead George and his fellow fox hunters on one fruitless chase after another, inventing new wrinkles and wiles as he goes along, and deriving much merriment from outwitting the hunters; as, of course, does the young reader, who also secretly and inchoately yearns to outwit the admirable authorities in his own life.

The young reader does not know this, quite; he revels first in the fun of the story and the dash of the tale and the sprint of the narrative and the glory of the art; but other things soak into him unawares, things that he only becomes aware of much later. For example, the respect and attentiveness and even reverence of the writer to and for the subject, and the way that text and art brilliantly hold hands and fit each other to create a third mysterious subtle thing, and the way that the second it takes to turn a page adds an extra instant of suspense to the story, and the way that a story, bound and published, acquires a certain grace and gravitas. Perhaps all of these things, soaking into a boy of nine in a corner of an old library in a small town, act as sparks in his later life, for that boy will also someday write books, and happily see them bound and published and stored in libraries, from the shelves of which he hopes, with all his heart, that even now, right this minute, as we sit here talking about books, a child is curling up in a chair with one of my books, and that child is increasingly delighted, and feels as if he or she has been waiting for exactly this book all his or her life, and here it is at last!—and if he hurries, he can gobble chapter after chapter with real and genuine glee, before his sister shows up to reclaim him from the library; but now, after this book, we know with absolute certainty that books and libraries and reading are countries we are going to live in daily for the rest of our lives. For that certainty I ought to have thanked Marguerite Henry many years ago; but I do so now, with the most sincere and heartfelt gratitude.