Most of the LPs in my parents’ collection were recordings of fairly serious fare, yet when I would browse through them as a child, I’d occasionally happen upon a disc that didn’t quite belong with all that Beethoven and Brahms. To take one example: an album called Rendezvous in Rome, released as part of RCA Victor’s Musical Travelogue series in 1959 and featuring the Melachrino Strings and Orchestra. Its moody cover shows the Eternal City at night, with a swarthy complexioned man in a pinstriped jacket playing his saxophone across the street from the Colosseum. “Not to exploit the already overworked cliché about all roads leading to Rome,” the liner notes on the back tell us, “but these two sides should really prove to be your way to an aural understanding of the Italian capital.” The album contains popular numbers (“Volare” and “Three Coins in the Fountain”), Neapolitan street songs (odd, given the ostensible focus on Rome), and some bits of pastiche put together by the orchestra’s bandleader, George Melachrino, an Englishman, it turns out, who was one of the kings of easy listening.

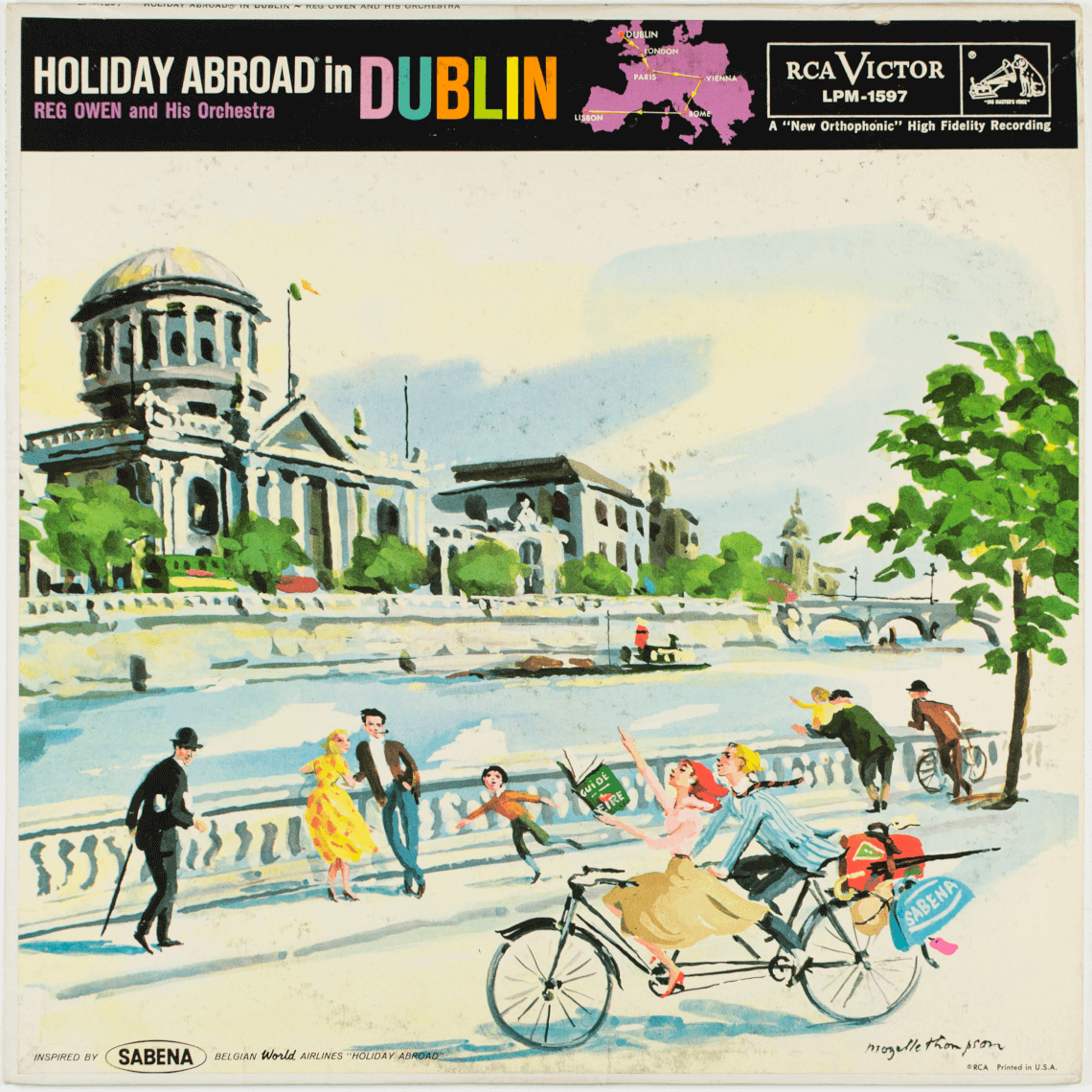

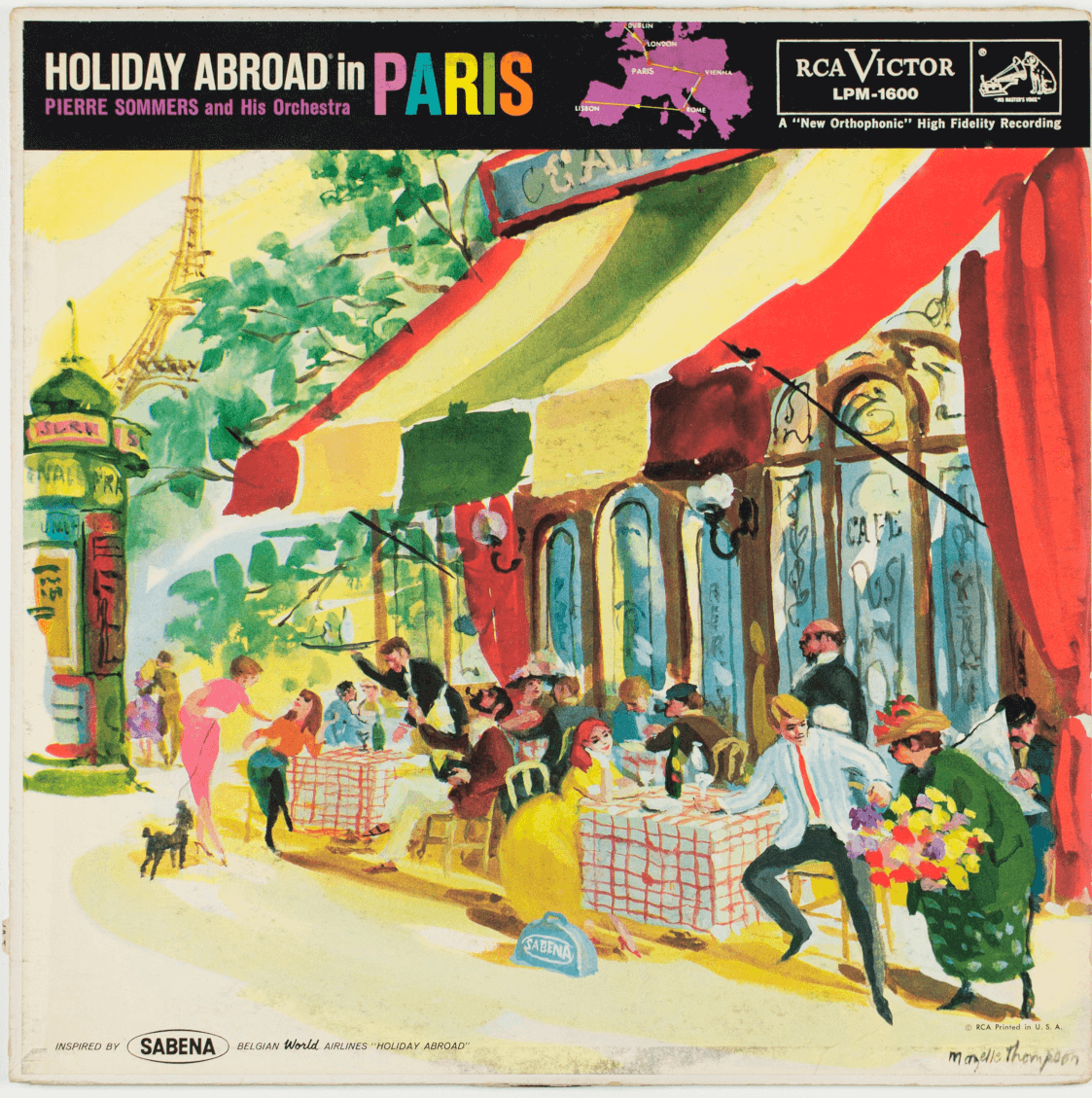

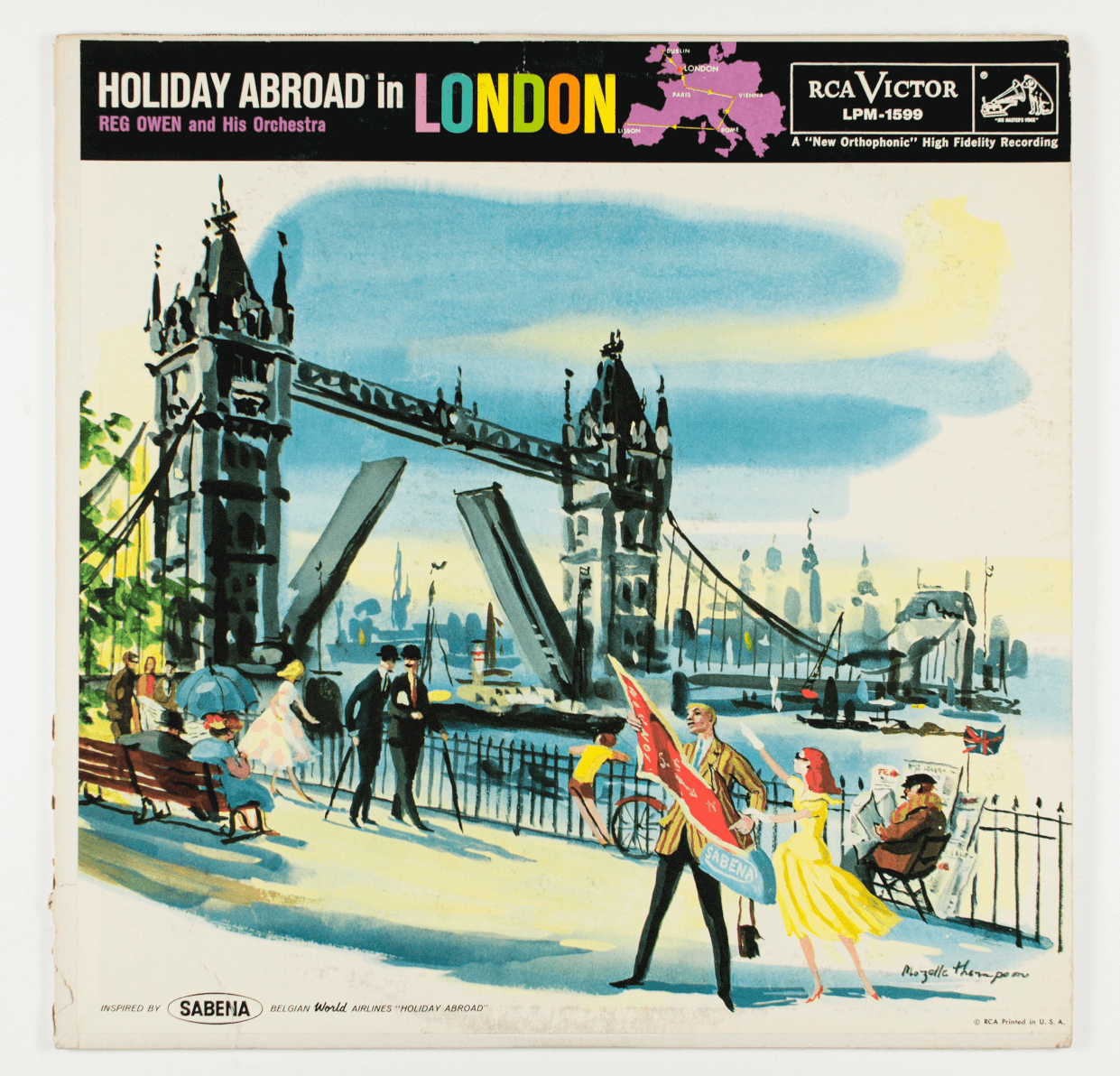

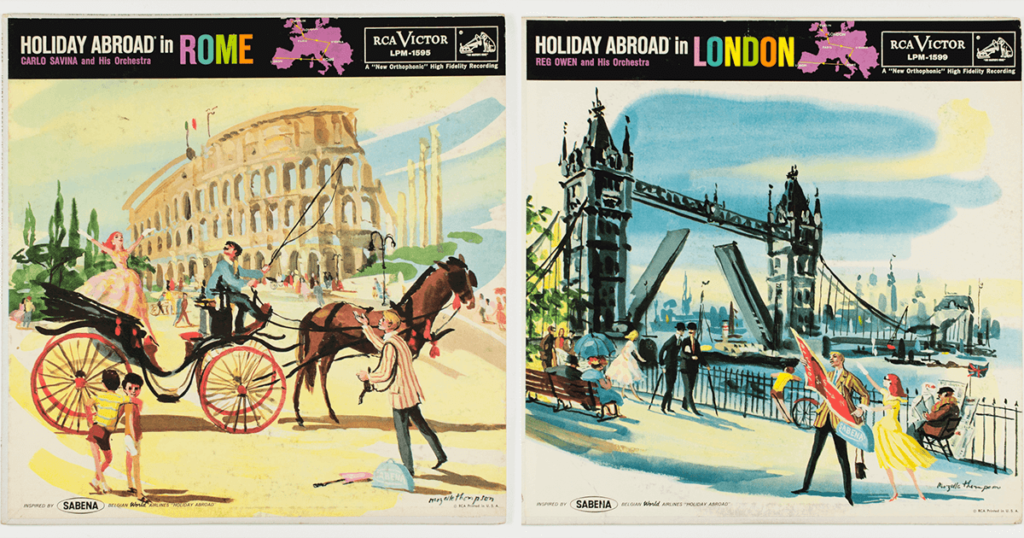

The record is in my collection now, and though it seems quaint and more than a touch naïve, I have an odd nostalgic fondness for its genre: the postwar travel album, as much a cultural phenomenon of its time as the luncheon martini or floor-to-ceiling glass. With the dawning of the jet age, a time when travel was perceived to be both stylish and sexy, the record industry sought to capitalize by appealing to those Americans now able to take an exotic journey abroad—or to those who simply wished to imagine and dream. Lately, I’ve been ogling many of these album covers in a new book by Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder called Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America. These records—Holiday Abroad in Paris, Berlin by Night, A Visit to Finland, Holiday Abroad in London, and Japan: Its Sounds and People, to name just a few—served as souped-up tourist brochures, the authors write, their liner notes filled with enticing Kodachrome photos and often containing tips on how to compose a foreign travel itinerary of your own. These records, the authors write, introduced the charms of Big Ben, the Eiffel Tower, and the Havana Hilton to millions of aspirational Americans.

You’d only find light fare on these albums, though classical music producers exploited the American thirst for the exotic, too. I have two old LPs of this sort that I put on from time to time, both featuring Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony. The cover of Vienna depicts two older Austrian men in native garb having a friendly street-side chat. The lavish booklet includes a long essay on Vienna and the waltz, with handsome photographs of the Heldenplatz, the Ringstrasse, and Schönbrunn Palace. The music is what you’d expect: “On the Beautiful Blue Danube,” “The Emperor Waltz,” “The Morning Papers,” and so forth. The pieces Reiner conducts on Spain—by Enrique Granados, Manuel de Falla, and Isaac Albéniz—are also somewhat predictable, and its booklet is no less evocative, with black-and-white and sepia-toned photographs of the Iberian countryside, the bullring, a fisherman bringing in the day’s catch, and two elegant ladies with flowers behind their ears.

It’s easy to look down upon, even to mock, the midcentury travel album. I don’t mean the Reiner recordings, which may swim in familiar waters but are wonderful performances all the same. I’m talking about Rendezvous in Rome and Holiday Abroad in London and Honeymoon in Paris, with their idealized and sanitized views of the Continent and beyond. Still, they are evocative all the same, artifacts from a far less jaded era. In this sense, they remind me of a few of my mother’s cookbooks that are now on my own shelves—beaten-up mass-market paperbacks from The Wonderful World of Cooking series, published in the early 1960s. These books aren’t remotely in the same league as the roughly contemporaneous masterpieces by Elizabeth David or Alice B. Toklas, and the recipes are simplified and Americanized, yet at the time of their publication, the volumes were wonderfully democratic in spirit, attempting to give every home cook in this country some sense, however approximate, of what might be found in France, Spain, Italy, Belgium, or Portugal. The series editor, one William I. Kaufman, who happened also to be the man behind the Thomas Cook and Son Travel Guides, describes one memorable al fresco meal he cooked at home, from recipes in one of these books, replete with checkered tablecloth and straw-encased bottles of red wine, in which the atmosphere was “a welcome change from the barbecue cookery so readily identified with the American backyard.”

Rendezvous in Rome and its ilk may have traded in cliché, and they may have ultimately encouraged the kind of tour-package holiday so hilariously mocked in movies such as the 1969 romp If It’s Tuesday, This Must Be Belgium. Yet is the hipster of today, prowling the back alleys of northern Thailand, posting pictures of the blood soup he had for lunch—and tallying up the likes on Instagram in the process, like so many notches on a bedpost—treating travel as any less of a commodity? Is it even possible to experience real authenticity, whatever that is, anymore? Once you accept that the answer might well be no, you can sit back and enjoy the likes of George Melachrino and his orchestra—not every day or even every week, but once in a while, when you want to feel that quiver of nostalgia—without any trace of irony or shame.