A Disposition To Be Rich: How a Small-Town Pastor’s Son Ruined an American President, Brought on a Wall Street Crash, and Made Himself the Best-Hated Man in the United States, By Geoffrey C. Ward, Knopf, 420 pp., $28.95

Nathaniel Hawthorne was spooked. Haunted by forebears who whipped Quakers till their backs turned to jelly and dispatched without regret suspected witches (mostly women) to Gallows Hill, Hawthorne nonetheless quieted his tender conscience by changing his name (he added a “w” to the family Hathorne) and scribbling some pretty amazing tales of bygone days.

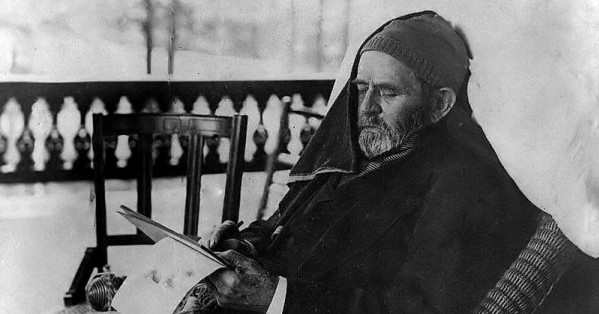

Family ghosts also haunt Geoffrey C. Ward, the author of such superb biographies as A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of FDR and the coauthor, with Ken and Ric Burns, of such blockbusters as The Civil War and Baseball. Ward has been mulling over the story of his great-grandfather for 50 years—and no wonder: though Ferdinand Ward didn’t hang witches, his legacy is almost as spellbinding. For as the long subtitle to this riveting new book makes clear, Geoffrey Ward’s great-grandfather left an unnerving inheritance not easily brushed aside. “If you cannot get rid of the family skeleton,” Ward quotes George Bernard Shaw in the book’s epigraph, “you may as well make it dance.”

The dance begins with great-grandpa Ferdinand’s parents, two zealous American missionaries bound for India from Boston in 1837. But the Wards were not happy, what with the monsoons and the mosquitoes and the moths and the heat and their quarrels with other missionaries, with whom they often and self-righteously stopped speaking. The Wards felt aggrieved, as they would for the rest of their lives, about something or other; returning to America in 1846 and settling in Geneseo, New York, they’d essentially been driven out of India in disgrace.

Of Ferdinand’s parents, his mother, Jane Shaw Ward, seems the more difficult. A passive-aggressive, depressed person whose piety enriched her sense of deprivation, she once advised Ferd, as he was called, when he was locked up in Sing Sing, to imagine her riding in the country in the splendid carriage he’d bought her (albeit with pilfered funds); just think, she said, of “all the comfort and happiness that those whom you love are enjoying even though you cannot partake in the same.” This was one mean-spirited woman.

But she coddled Ferd, the beneficiary of her embittered conviction that virtue (hers) would not be rewarded in this world—a point of view Ferd would cynically adopt. And because his disputatious father was often spatting with colleagues and parishoners, Ferd became his mother’s “sole companion,” as Ward writes, “in the dark parsonage.” But where Hawthorne visited the sins of the dark house on the sons, Ward lays most of the blame for Ferd’s character on Ferd himself. At 15 Ferd was already spending money that wasn’t his, running up his parents’ tab, and borrowing from one per- son to pay off another. He hated working, was greedy, vain, and obsequious, and was always cadging sympathy.

Ferd went on to fleece some of the most important businessmen of his time. Leaving the dark parsonage for New York City in 1873 to clerk at the Produce Exchange (where brokers sold commodities they never saw, like grain and food), he soon managed to snag a rich wife, dip into her family’s fortune, and concoct a pyramid scheme that dwarfs those of Charles Ponzi and Bernie Madoff; Ferd would after all impoverish an American president.

With the financial backing of James D. Fish, head of the Marine National Bank, who may or may not have known what Ferd was doing, Ferd opened his own brokerage firm, having also induced the naive, affable Buck (Ulysses, Jr.) Grant to come on board. The Grant name, Ferd rightly calculated, would help attract big money. Grant & Ward, as the brokerage house was called, purchased and sold stocks and bonds—with, as the name falsely implied, the blessing of General Grant, though he later joined the firm as a silent partner. Ferd told investors he had inside information about government contracts.

But there were no government contracts. The whole thing was a hoax. Ferd used the same securities over and over again as collateral against loans. When paid at all, the huge dividends going to Mr. X actually came from money invested by Mr. Y. As Ferd blithely testified to the New York Supreme Court after the swindle came to light, “I had to rob Peter to pay Paul.” Ferd also managed to bilk funds from the city treasury and deposited the capital into his personal account, netting more than $9 million as well as a grand, well-staffed brownstone in Brooklyn Heights and a sumptuous 25-acre estate in Connecticut.

What’s remarkable about Geoffrey Ward’s book, however, is the tale behind the tale of Ferd’s tawdry rise and fall—that is, the story of how greed creates gullibility and how an appetite for wealth and a good time blinds otherwise intelligent men and women. Ferd’s dupes asked no questions about their securities as long as they were reaping huge profits and having fun. Even Fish, who breakfasted with Ferd almost every morning, never inquired about where his partner found the commodities in which he was (apparently) investing. As the lawyer for one defrauded investor later explained, the charismatic Ward “had the power of fixing his eyes on a man and willing the dollars out of his pocket.” Maybe, but even the most consummate con man needs a mark.

When Ferd’s house of cards came tumbling down, in 1884, he was considered not only a swindler but the man who sent the heartsick hero of Appomattox, now penniless, to his grave. The unwitting Buck and the credulous general had lost their shirts with Grant & Ward. Yet as the judge who sentenced him to 10 years in prison said, Ferd seemed without remorse for what he’d done. The judge was right. At Sing Sing, Ferd quickly figured out how to get the easiest work detail, the best cell, the best tobacco, expensive sheet music, and as much money, useful for bribing prison officials, as he could squeeze out of family and friends.

Then his long-suffering wife, Ella, showed some backbone. Left with their small child Clarence (Geoffrey Ward’s grandfather) and the cloying headaches she relieved with alcohol-laced patent medicines, Ella stood up to her self-pitying husband. She refused to sell off all her jewelry to supply him with more comforts—she’d already sold her diamond clips but had offered to sell the diamond from her wedding ring—and she drew up a will that left her entire estate to the support, education, and maintenance of Clarence until he turned 25, at which time he’d receive the remaining principal. Furious and, as usual, selfish, after Ella’s early death (too much patent medicine), Ferd tried to finagle the eight-year-old Clarence out of his inheritance, and when Ella’s family took the boy in, Ferd, released from prison, tried to kidnap him to grab hold of Ella’s estate.

Then his long-suffering wife, Ella, showed some backbone. Left with their small child Clarence (Geoffrey Ward’s grandfather) and the cloying headaches she relieved with alcohol-laced patent medicines, Ella stood up to her self-pitying husband. She refused to sell off all her jewelry to supply him with more comforts—she’d already sold her diamond clips but had offered to sell the diamond from her wedding ring—and she drew up a will that left her entire estate to the support, education, and maintenance of Clarence until he turned 25, at which time he’d receive the remaining principal. Furious and, as usual, selfish, after Ella’s early death (too much patent medicine), Ferd tried to finagle the eight-year-old Clarence out of his inheritance, and when Ella’s family took the boy in, Ferd, released from prison, tried to kidnap him to grab hold of Ella’s estate.

What’s also remarkable about this book is the author’s utter condemnation of his own great-grandfather as a sociopath without redeeming virtue. Never explaining away Ferd’s behavior, Ward reserves his sympathy for Ferd’s victims, like Ella. And Ward does not moralize. Like Hawthorne, he’s interested not only in character but also in the consequences of one’s actions, and so he can vividly exorcise at last, without excuse or apology, his reprobate forebear. If there’s a lesson to be learned for our or any Gilded Age, it is grotesquely simple: anything that seems too good to be true probably is.