Concerto in Beans and Rice

Jazz maestro Paquito D’Rivera turns 70 this year, with a major collaboration with Yo-Yo Ma in the works

When Paquito D’Rivera and his jazz quintet began their set at the Jazz Forum supper club in Tarrytown, New York, one evening last December, the audience stopped its clatter at the cheerful pop of a single chord, struck by pianist Alex Brown. After a pause, Brown played a sparkling melody that became a geyser of cross-hatched harmonies and syncopated rhythms as the rest of the quintet joined in. Chattering like a skylark on his clarinet, D’Rivera carried on a rollicking musical conversation with Brown, Diego Urcola on valve trombone and trumpet, Oscar Stagnaro on bass, and Mark Walker on drums and percussion. The surge in tempo from allegro agitato to presto in the final section prompted audible gasps from some members of the audience. “That piece was written by a great Puerto Rican composer—Frédéric Chopin,” D’Rivera quipped. “It’s called ‘Fantasie-Impromptu.’ ”

During the remainder of the set, the quintet served up a mélange of jazz, classical, and Latin music that included a piece D’Rivera composed for Ballet Hispánico based on the danzón, a popular dance form from his native Cuba; a blues that Urcola wrote to honor the Argentine tango master Astor Piazzolla; and Brown’s jazz arrangement of a bolero by the Mexican composer Armando Manzanero. That last number was an exhilarating set-closer that brought the entire audience to its feet. As the applause subsided, D’Rivera said, “Thank you for joining us on a journey through Latin America on the wings of the jazz.”

D’Rivera is a restless spirit who defies easy categorization. He is Cuban by fervid temperament, even though he has not set foot in his homeland for nearly four decades. “You can take a Cuban out of Cuba,” he said. “But you can’t take Cuba out of a Cuban.” He has been honored as a jazz master by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, but his work as both a composer and a performing artist transcends conventional musical boundaries. In addition to winning multiple Grammy Awards for jazz and Latin jazz over the years, D’Rivera was a member of the ensemble that cellist Yo-Yo Ma assembled for Obrigado Brazil, which won a Grammy Award for Best Classical Crossover Album in 2003. A year later, D’Rivera took home a Grammy of his own for Best Instrumental Composition for “Merengue,” based on an exotic Venezuelan rhythm, which appeared on Obrigado Brazil: Live in Concert.

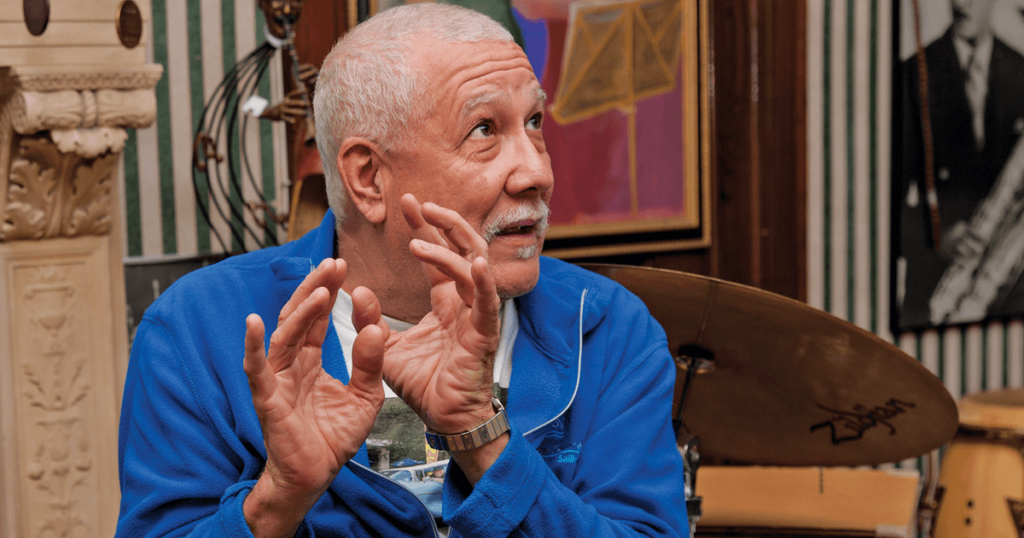

This is a landmark year for D’Rivera, who turns 70 this June and has a frenetic international tour lined up. “I plan to celebrate all year long,” he said during a conversation we had last December at his home in North Bergen, New Jersey, which affords a clear view across the Hudson River of midtown Manhattan. D’Rivera took a break from touring last fall to finish writing a symphonic work commissioned by the Kennedy Center. Called the Rice and Beans Concerto, the composition pays tribute to the historic contribution black Africans and Chinese made to Cuban culture. “Both races came to Cuba as slaves,” he said. “The Chinese came under contract rather than in chains, but they were treated like slaves. I put the African element and the Chinese element together in the concerto.” The work also celebrates D’Rivera’s longtime friendship with Ma, the Kennedy Center’s artistic adviser at large.

The concerto was conceived in jest a decade ago. “Yo-Yo was a little nervous when we began working on Obrigado Brazil because he had never played that kind of music,” D’Rivera recalled. So they got together at D’Rivera’s house for an informal jam fest. “I invited this fantastic Israeli pianist, Alon Yavnai, who said he would be happy to play Brazilian music with Yo-Yo, but only if Yo-Yo agreed to play the Brahms Sonata for Cello and Piano with him—and hearing them play that beautiful sonata together in my home was like being in heaven.” As the jam fest progressed, D’Rivera’s mother, Maura, made lunch for everyone.

“She cooked black beans and rice,” D’Rivera said. “When we finished eating, I told Yo-Yo, ‘One of these days I’m going to write the Rice and Beans Concerto for you and me to play.” From then on, D’Rivera called Ma “Rice,” and Ma called D’Rivera “Beans.” But D’Rivera didn’t realize that Ma had taken seriously his offhand remark about writing the concerto. “Years later I got a call from somebody at the Kennedy Center who said, ‘Do you still want to write the Rice and Beans Concerto? ’ I said, ‘The what?’ I had completely forgotten about it.” Now the challenge is finding a date for the work’s premiere at the Kennedy Center, where the concert schedule for the National Symphony Orchestra is already set through much of 2019.

Ma and D’Rivera are an odd but remarkably simpatico musical couple. “He’s an Asian born in Paris and trained at Juilliard. I’m a crazy Caribbean,” D’Rivera said. “He’s very polite, and I’m very explosive.” D’Rivera is an incorrigible practical joker. Ma’s dignified but openhearted sense of humor was evident during the Obrigado Brazil tour, when the ensemble gathered at a communal table in a luxurious restaurant in Hong Kong for an after-concert meal. “Yo-Yo suddenly came through the kitchen’s swinging doors, wearing his black slacks and white shirt, with a white napkin on his forearm and a bottle of very good wine, and started serving everyone in the restaurant,” D’Rivera said. “Later I went out to get some fresh air, and an American guy who was leaving the restaurant said, ‘Did you see that crazy guy who looked like Yo-Yo Ma serving wine to everybody? Then he had the nerve to sit at your table and eat all your food. Amazing, isn’t it?’ ”

Like Ma, who began playing cello at age four, D’Rivera was a child prodigy whose father began nurturing his musical talent when he was still in the cradle. Tito D’Rivera, a classical saxophone player and the Havana sales representative for the Selmer musical company, serenaded his son all day. “I had a paciphone—a saxophone pacifier,” said D’Rivera. His first instrument was a curved soprano sax designed for easy handling by a kid; the first melody he mastered was a jingle for Camay soap. He made his public debut at six playing a Cuban habanera for his kindergarten graduation. At the age of eight or nine, D’Rivera fell in love with swing music when his father brought home the album Benny Goodman: Live at Carnegie Hall. “When my father said, ‘Carnegie Hall,’ I heard ‘carne y frijole,’ ” D’Rivera recalled. “ ‘No,’ he said, ‘Carnegie Hall.’ I immediately got it in my head that I wanted to be a musician in New York.” Then D’Rivera’s father put a recording on the turntable of Goodman playing the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. “Duke Ellington once said there are only two kinds of music—good and the other stuff—and that’s the mentality I inherited from my father,” D’Rivera said.

When Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba a couple of years later, his apparatchiks echoed their Soviet counterparts and denounced jazz as a product of American imperialism. Meanwhile, D’Rivera studied the classical canon at the Havana Conservatory of Music, landed his first professional gig at age 15 playing with a musical theater orchestra, and developed his jazz chops in informal jam sessions with pianist Chucho Valdés. He performed with the army band during a mandatory stint in the military and was surprised when he was released six months early and reassigned to a government-sponsored jazz big band. “I couldn’t tell you, even under duress, why the hell Orquesta Cubana de Música Moderna was established,” he said.

Eventually, D’Rivera and Valdés cofounded the small ensemble Irakere. “My house in those days was like a center for jazz,” D’Rivera said. One day in April 1977, one of the founding fathers of Afro-Cuban jazz showed up on his doorstep while he was out. “When I returned home, the guy at the corner grocery store said, ‘There was a black guy dressed in a cape and two-brimmed hat like Sherlock Holmes looking for you,’ ” D’Rivera recalled. “I thought, ‘That must be Dizzy Gillespie. But that’s impossible.’ Fifteen minutes later, the political police knocked on my door and said, ‘Take your instrument with you because there are some people we want you to see.’ ” Gillespie, Stan Getz, and several other musicians had come to Havana on the cruise ship Daphne for a goodwill tour, which Cuban officials kept mostly on the QT. Three years later, D’Rivera defected while on an international tour with Irakere. Gillespie subsequently helped catapult him into the top tier of jazz musicians by inviting him to be his guest artist on a European tour. “He was very generous to me,” D’Rivera said.

“Yo-Yo is like Dizzy,” D’Rivera said. “He is a catalyzer who brings people together.” The inspirational influence of both men on D’Rivera’s life and music was palpable during a sneak preview of the Rice and Beans Concerto in the sunlit home studio where D’Rivera refines his compositions with the aid of the professional music software program Sibelius. Standing in front of an elevated work station with a two-tier digital piano, a computer keyboard setup, and an oversize monitor, he joked, “I work like Hemingway, only I don’t have any shotgun here.” Suddenly, the synthesized sounds of an orchestra filled the room. “The first movement is called Beans,” D’Rivera said. “Beans are what they used to feed the slaves in Cuba. No meat. Just beans. This is the most jazzy, African movement and reflects who I am.” Shades of Gillespie’s early experimentation with Cuban and Brazilian rhythms are evident, as are elements of Brazilian chorinho mixed with a Cuban danzón and guaracha.

In performance, the concerto will feature a small combo—clarinet, cello, piano, percussion, and Chinese erhu—engaging with a full symphony orchestra. “It’s like a concerto grosso,” D’Rivera said. For the upbeat first movement there will be just two soloists—D’Rivera on clarinet and Ma on cello.

The second movement, Rice, is structured around a pentatonic melody with some Cuban danzón in the middle. “This is where I introduce the Chinese erhu, which I’m hoping to convince Yo-Yo to play,” D’Rivera said, as he cued up the synthesized version on Sibelius. “He has an erhu, but he is a perfectionist. So I don’t know yet whether he will agree. If he does, we’ll give the cello part in this section to the principal in the orchestra.” The instrumentation is spare: strings, piano, and some light Cuban percussion. “The movement is very polite,” D’Rivera said. “Like Yo-Yo the waiter, the bartender.”

The third movement, The Journey, begins with an instrumental interpretation of an Afro-Cuban religious chant—a call and response with a percussionist tapping out a Cuban danzón rhythm—and the cello and erhu picking up the main melody. “It’s an allegory of the journey of enslaved Africans and Chinese to the New World,” D’Rivera said. D’Rivera may play some passages on a suona, a double-reeded horn with a high-pitched sound used by traditional Chinese musical ensembles in wedding and funeral processions and outdoor festivals. “In Cuba they call it la corneta china, and it is so loud it can be easily heard over drums.” Waving his right hand like a conductor as the rousing finale arrived, D’Rivera said, “I have to keep my fingers crossed that the classically trained musicians can forget their Brahms for a while and follow the rhythm. Sometimes the conductor has even less sense of rhythm than the instrumentalists, so it is problematic.”

The wait goes on for the Kennedy Center premiere, but in the meantime, D’Rivera has completed a reduction of the concerto for violin, clarinet, cello, and piano—the only instruments on hand when French composer Olivier Messiaen, then a prisoner of war in Görlitz, Germany, premiered his Quartet for the End of Time in January 1941, at the Nazis’ Stalag VIIIA camp. “There are not many pieces written in that format,” D’Rivera said. “I would be honored if Rice and Beans and The End of Time could be performed in the same chamber music program.”