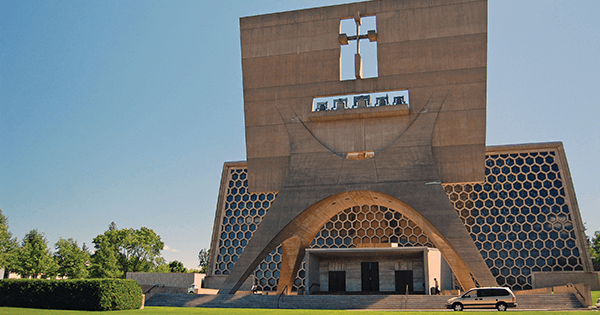

An hour away from Minneapolis, a wild soaring sculpture rises from the campus of Saint John’s University, just across the interstate from Collegeville, Minnesota, population 3,000. This tilting, concrete structure, 112 feet tall and known as the Bell Banner, stands in front of Saint John’s Abbey, a monumental church completed in 1961 by the modernist architect and designer Marcel Breuer. According to I. M. Pei, the church would be considered one of the most famous architectural works of the 20th century—were it not located on this isolated northern plain. But part of its obscurity surely has to do with the architect himself.

The Hungarian-born Breuer designed more than 70 houses and created such iconic structures as UNESCO’s headquarters in Paris and the Atlanta-Fulton Central Library. His furniture, such as the Wassily chair (created when he was a student at the Bauhaus), is still much sought after. But after his death in 1981, Breuer became almost a forgotten man.

These days, however, he is enjoying a resurgence. A new book on the architect by Robert McCarter is forthcoming, and in New York the museum formerly known as the Whitney has reopened to acclaim as the Met Breuer, housing works from the Metropolitan Museum’s modern and contemporary collections. Breuer designed the Whitney’s concrete edifice on East 75th and Madison Avenue in 1966. Walking through its elegant galleries not long ago, admiring the trapezoidal windows and gorgeous slate floors, I wondered how Breuer ever fell from grace to begin with.

In the 1950s, Breuer moved away from glass façades, a signature element of the International Style, in favor of precast or prefabricated concrete. The advantages of concrete were considerable. It could be used for the walls as well as the support for a building. Heating and plumbing could be buried inside. Best of all, it could be sculpted.

Breuer came to believe that an architect’s “moral duty” was to design structures that showed off the reasons for their existence. And there was a further philosophical bent to his method as exemplified in his approach to Saint John’s Abbey: “How much we will be affected by the building, how much it will signify its reverent purpose will depend on the courage it manifests in facing the ancient task: to defeat gravity and to lift the material to great heights, over great spans—to render the enclosed space a part of infinite space.” Breuer became convinced that concrete would enable him to realize this dream, especially at Saint John’s Abbey.

Built for members of what was then the largest Benedictine order in the world, the church today accommodates 1,700 worshippers and seats a choir of 300. In front stands the high campanile, the Bell Banner, as Breuer dubbed it, inspired by banners flown in religious processions. At its 100-foot-wide top, he carved out a rectangular opening for a large cross. Five large bells sit on a platform below, and the entire concrete panel—his ode to cubism—is perched on four concrete arches. In all, 2,500 tons of concrete went into its making. His ability to mold this material is evident throughout the church, no more so than on its lofty side walls, where a series of Vs fold into each other.

Breuer wasn’t the only architect expressively using concrete in the mid-20th century. Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, and others were heralded for their experiments in the form. But the public would turn against the explosion of concrete structures, against what detractors called Brutalist architecture.

As his career progressed, Breuer’s devotion to the material led to his falling out of favor. It did not help that one of his most-talked-about later commissions was a tower to be placed atop Grand Central Terminal in New York. The project provoked an outcry, and the ensuing campaign to preserve the original structure, with Jacqueline Onassis among the loudest voices, became a popular cause. McCarter has said that Breuer felt “personally burned by everyone who turned against” the project.

In the Met Breuer, the scale of the galleries and the quiet, monumental feeling exuded by its concrete walls allow for extraordinary spaces in which to contemplate art—something rare in museums today. There is an almost palpable spiritual feeling, similar to what the worshippers inside Saint John’s Abbey (“without doubt Breuer’s finest building,” McCarter said) must sense to an even greater degree. Indeed, Breuer’s expressive concrete structures can evoke a deeply powerful response in those willing to experience them on their own terms. Few architects, it seems, are more deserving of a comeback.