I suppose I can no longer avoid writing about the subject that is on everyone’s lips: Donald J. Trump. It makes me queasy to write about him, because I don’t think I have anything original to say, nothing that hasn’t been analyzed and reprinted a million times. In general, I have tried not to worry too much about the political campaign—I have even promised myself not to panic, not to let it spoil my summer. And yet I find myself obsessing about this man, who nightmarishly haunts me like a demented Porky Pig. What is it about him that is so transfixing? He says such idiotic things, which no American politician before has ever dared utter: deriding the parents of a dead soldier, or vowing to block Muslims from entering the country, or claiming he can get no justice from an American-born judge with Hispanic roots, or mocking John McCain because he was a P.O.W. We all know the list, and in a sense we—or I—looked forward each week to hearing some new, outrageously imbecilic pronouncement added to it, even as I cringed at the latest affront.

There is certainly something fascinating about stupidity, especially when it is blatantly made public: it becomes a kind of negative intelligence. Oh, I know, he may be cunning and bright in his way (so they say), but the real attraction, the essence of his charisma, is that he is remarkably stupid. Not crazy, just stupid. And proud of it. Or doesn’t know he is stupid. He reads nothing; he only watches television for “briefings” on foreign affairs. He is like a Black Hole of Intellect. I, who have spent my whole life pathetically trying to snatch at a few grains of intelligence, cannot help but see him as my doppelganger, my long-lost evil twin brother.

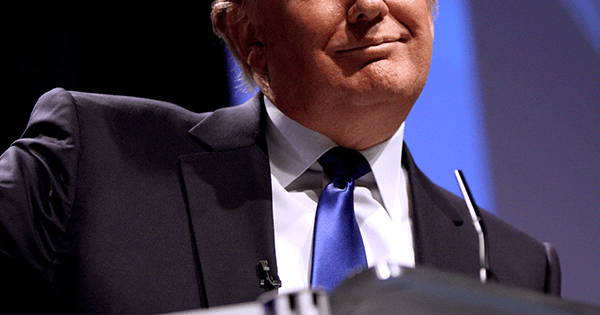

Before the Republican National Convention, I would sometimes watch the man giving speeches, intrigued for 10 minutes by his declarative sentences of eight words or less, by the glibness with which he lied, by his egotistical self-flattery and the Mussolini profiles he struck. But then, during the week of the RNC, I couldn’t take it any more: I was horrified, revolted; I had to switch to the Mets game when Trump launched into his sinister acceptance speech. I could no longer find him perversely entertaining; rather, he seemed to be hectoring me personally, reaching through the television set to insult and bully me. He was saying to me: “You, bookworm, I have no use for you and your kind. You’re weak! I will trample over you.”

It made me frightened. And beyond that, it made me feel lonely. If this is the standard by which masculine success is judged in our country, then I must accept forever being an outsider. Ever since high school, when I realized that I was somewhat different from most other students—a too-sensitive nerd (though we didn’t have that word then), an egghead—I have made my peace with abnormality. It didn’t bother me: normal was not an option. But somehow, Donald J. Trump, by his very self-presentation, has plunged me into insecurity. I even question my right to speak up, if I cannot counter his challenge to the life of the mind with dazzling, original witticisms.

I suspect that all writers and intellectuals identify as immigrants of a sort, struggling to fit into or at least accommodate the often alienating mass culture in which they find themselves. So when Trump goes on the attack against potential immigrants, though my grandparents came to this country, I feel personally vulnerable. The writer in me feels diminished and wants to hide.

The civic-minded side of me thinks this is nonsense. I must do all I can to defeat this charlatan: time to ring doorbells, make cold calls, send Hillary more money. Aside from her many qualifications for the Oval Office, she is a politician, which is to say, someone who alters her position based on what is achievable at any moment, even conceals some of her interiority at times—and so what? Are we such purists, such adolescent moralists, that we expect our leaders to be transparent or saintly? But Donald J. Trump is another story. He is not a politician, or he would never say the things he does. He is evil, in the specific sense Socrates defined the word: evil as a kind of ignorance. When all is said and done, I don’t understand the type of man who would embrace ignorance with gusto. It’s all I can do to squeeze out these few hundred words about him—and then, let’s expect to hear no more about Trump in this blog.