The Tower and the Ruin: J. R. R. Tolkien’s Creation by Michael D. C. Drout; W. W. Norton, 384 pp., $35

During preproduction of The Lord of the Rings, the hugely successful film trilogy, director Peter Jackson gave a speech to the members of the design team. He asked them to make believe that J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel about hobbits and wizards “is real; that it was actually history; that these events happened.” He then told them to go a step further and pretend that “we’ve been lucky enough to be able to go on location and shoot our movie where the real events” took place. Although the story is high fantasy, Jackson wanted the costumes, creatures, and weapons to have a degree of verisimilitude that would set his movies apart from standard Hollywood epics. And they did: The trilogy grossed nearly $3 billion worldwide, and its final installment, The Return of the King, swept the 2004 Oscars.

To many readers, The Lord of the Rings “seems like something traditional and historical rather than being the literary invention of a twentieth-century Oxford professor,” writes Tolkien scholar Michael D. C. Drout, and plunging into its pages “feels like entering a world rather than just reading another book.” In The Tower and the Ruin, Drout sets out to explore the literary techniques that Tolkien used to achieve this remarkable effect. Not for the faint of heart—Drout delves deep into the author’s back catalog—The Tower and the Ruin is an important addition to Tolkien studies and a welcome companion for Middle Earth’s most loyal readers.

One of Tolkien’s devices for authentic world building was to place a frame around his narratives—“a story that wraps around the central story, giving it a context and, often, a reason for its existence.” Taken to excess, frames can heighten a sense of fantasy rather than realism. Think of Wes Anderson’s 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel, which opens with a girl holding a book, then cuts back in time to the author of the book, who in turn recounts the story an old man told him decades earlier about the old man’s formative years. The effect is a nesting doll of narrative so elaborate as to beggar belief. Anderson draws attention to his own artifice, establishing a charming idyll to be enjoyed but not taken too seriously.

Tolkien used subtler framing devices, drawing on the medieval literature he studied at Oxford, like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The Lord of the Rings takes a lighter approach to the book-within-a-book conceit. Readers are given to understand that the novel they are reading is itself a document written by the characters Bilbo Baggins and his nephew Frodo. Near the end of the book, Frodo hands the nearly completed manuscript to his friend Sam to finish. In The Hobbit, Tolkien used an even cleverer framing device by having an intrusive narrator reinforce the book’s status as children’s literature. (“I don’t suppose you would have done half as well yourselves in his place,” the narrator gently scolds.) Drout contends that readers of the two novels “are not supposed to think that the stories are inventions, but rather discoveries.”

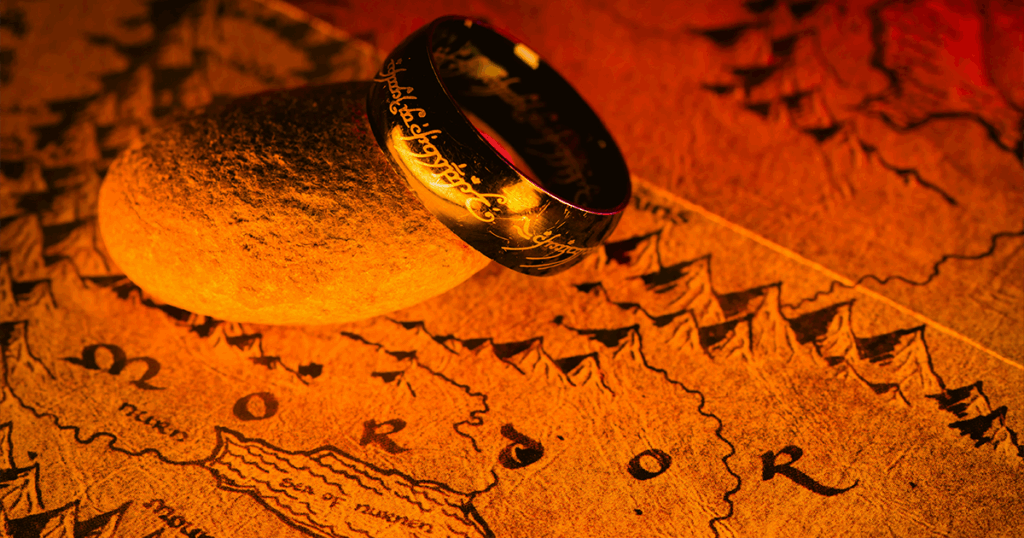

Tolkien likewise filled his novels with materials compiled over time, making them feel like a “textual patchwork” rather than a book conceived by a single modern author. The Lord of the Rings overflows with songs, poems, languages, and old myths repeated down the generations. This history adds layers of accumulation to the finished novel—understandably, since it represented the work of a lifetime. As a professor of philology at Oxford, Tolkien spent decades creating mythical languages, maps, and epics for the broader world of Middle Earth—his “legendarium.” If allusions to this vast universe seem convincingly lived-in throughout The Lord of the Rings, it is because they are.

Sometimes, however, Drout threatens to give Tolkien more credit than he is due. He contends, for example, that internal contradictions in The Lord of the Rings reinforce the sense that it is a compilation of ancient texts, since historical sources never agree on all points. Yet this assertion risks turning scriveners’ errors into meaningful touchstones. For instance, Tolkien had his elves ride horses without bridles or bits—except when he didn’t. Drout writes that Tolkien “either did not catch or decided not to change” one wayward mention of an elf’s bridle and bit. It seems a stretch to view mistakes of this kind, inevitable in such a long and detailed novel, as particularly meaningful weaves in its texture.

Drout also does not explore the most immediate element of Tolkien’s uncanny authenticity: his use of grandiloquent, archaic, and at times pompous language. His writing is instantly recognizable, as in this passage from The Two Towers:

The hobbits stood now on the brink of a tall cliff, bare and bleak, its feet wrapped in mist; and behind them rose the broken highlands crowned with drifting cloud. A chill wind blew from the East. … South and East they stared to where, at the edge of the oncoming night, a dark line hung, like distant mountains of motionless smoke.

The passage is full of characteristic Tolkien high style. The writing is formal, old-fashioned, and romantic, conjuring up the distant past even at the level of the word and phrase.

Drout’s book takes its name from an arresting insight: Tol-kien’s novels, he observes, are filled with towers, many of which end up as overgrown ruins. These relics organically establish history, but they also signify Tolkien’s abiding tone of melancholy for an unrecoverable past of unspoiled pastoral landscapes—an England that preceded two world wars. “A ruin preserves the memory of what has been at the cost of making it impossible not to recognize the permanence of the loss,” Drout elegantly writes.

Loss hovers over The Tower and the Ruin as well. Drout vividly remembers his father reading to him the famous opening line, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” In turn, Drout read Tolkien’s books to his son. The Tower and the Ruin is dedicated to those two men, both of whom died while the book was being written. Drout writes affectingly about his lost parent and child, and the ways Tolkien’s novels brought them together. The Tower and the Ruin ultimately reminds us that great literature serves us best when it is not merely written and read but shared.