The End of The Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America by Greg Grandin; Metropolitan Books, 384 pp., $30

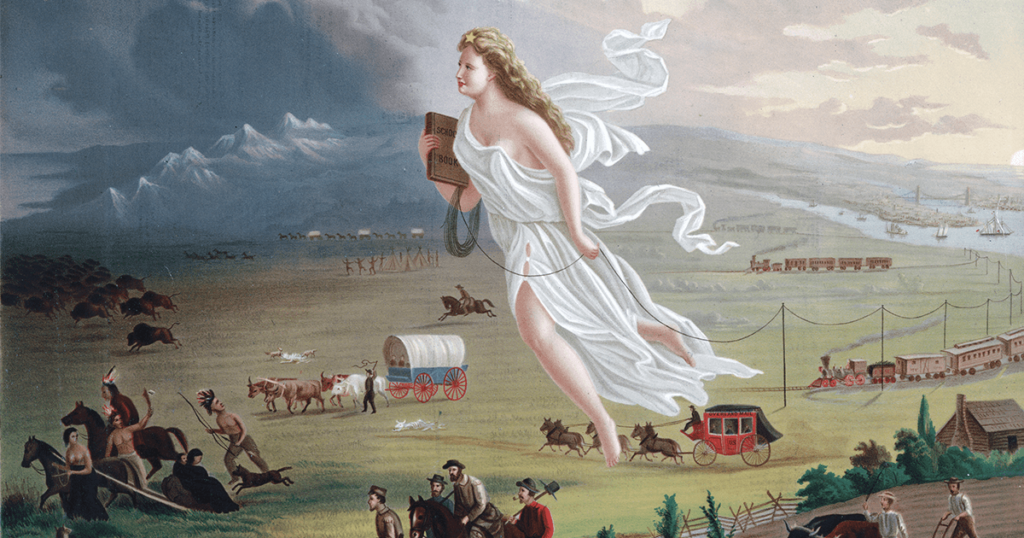

“Do we really need another book on the Turner thesis?” a relative said with a sigh, flipping through my copy of Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth on a family getaway. Granted, there’s a textbook whiff of social studies about the book’s murky cover art, its vague subtitle, and most of all, its focus on Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis.

Fortunately, Grandin, a Bancroft Prize winner and the author of six previous histories, doesn’t care what my relatives, or I, found boring in middle school. The End of the Myth kicks hard-packed certainties into dust as he strides across three centuries in pursuit of his ideas.

Like Turner, Grandin asserts that both the fact and the idea of an ever-expanding frontier are keys to America’s political culture and identity. But where Turner saw “an unprecedented expansion of the ideal of political equality,” Grandin sees self-delusion: “A constant fleeing forward allowed the United States to avoid a true reckoning with its social problems.” Europe had grown close and crowded, and periodically consumed itself in social and religious conflict. But America had an escape hatch. It had space, and with it the option of projecting its problems outward. In practical terms, this meant diluting class tension without infringing on property rights. “The promise of a limitless frontier meant that wealth wasn’t a zero sum proposition,” Grandin writes.

America need not fear revolt because the frontier enabled it to maintain, in the words of historian Peter Onuf, a “permanent revolution.” But perpetual expansion was also a tacit admission that America’s problems “wouldn’t be solved within the existing terms of social relations and political power.” The westward advance was, paradoxically, a political retreat.

It’s a simple idea, but Grandin, a professor of history at New York University, uses it to supply rich new context to familiar events and pluck neglected ones from the shadows. The USS Maine gets more ink than Pearl Harbor; the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo more than Appomattox.

Grandin introduces his section on the Revolutionary War, for example, by highlighting land speculation west of the Alleghenies by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and others in defiance of King George III, who sought to protect his Native American allies there. With money on the table, Grandin argues, the founders imbued expansion with practical and moral justification. “Extend the sphere,” James Madison advised, because this would dilute the power of factions, breaking up society into diverse interests that would “check each other.”

But this method of diluting factionalism unleashed new forms of it. As the federal government sought to control expansion and behave like a sovereign nation in the eyes of the world, it enforced treaties with Native Americans that enraged land-hungry settlers. Grandin captures an essential flavor of American politics when he observes that the “hostility British settlers felt toward the British Crown” was “transferred to the federal government.”

Grandin is a third of the way through his narrative before he takes the story back to Turner, the mild Midwesterner who presented his influential thesis in 1893, arguing that American ideals of equality arose through expansion west. Turner’s view was paradigm-shifting, Grandin writes, but also strangely bloodless—especially since Turner was certainly aware of the forced removal of Winnebago and Menominee tribes from near his Wisconsin home during his childhood.

Turner’s contribution was to unchain the concept of frontier from its physical reality and let it “float free as an abstraction,” Grandin writes. The frontier myth would soon apply equally to overseas military power, international trade, and technological advancement. But at last, it has shattered—the “end of the myth” of the book’s title, its demise embodied by President Trump’s proposed border wall. “Trumpism is extremism turned inward,” Grandin writes.

Grandin gives careful attention to rhetoric—the way mere clichés and modes of expression work to shape history. Early on, for instance, he flags Jefferson’s tendency to lapse into the passive voice when writing of the expulsion of Native Americans. A century of euphemistic dodges on the subject followed. Elsewhere, he considers the word frontier, once simply a synonym for boundary but later not only “an adjective, a noun,” but “a national myth.”

Nowhere, though, is his focus on rhetoric more fruitful than in a chapter on the “safety valve.” Grandin starts small, explaining how this 17th-century French invention was meant to control pressure in a boiler and how it was misused by steamboat captains who risked blowing up their vessels by propping it open for speed. But as he traces the rise of the “safety valve” as a metaphor and follows its reworking in American political parlance over generations, the discussion becomes the kind of higher-order analysis that gathers steam, propelling the whole of his thesis.

So thoroughly did Americans internalize the imagery of a safety valve that the metaphor merged with the practical measures it was invoked to justify. Americans flogged the notion of venting steam to address every contradiction and dissonance in their young country, but especially those involving caste and class. Constitutional restraints were praised as “the safety valve in the political engine.” The franchise was a “safety valve,” and so was universal education, checks on vice—and vice itself. Pro-slavery voices called enslaved women “safety valves” for white lust. Abolitionists called Africa a “safety valve” for freed slaves. The annexation of Texas was a “safety valve,” as were Western land giveaways, imperial ambitions, and aspects of the New Deal, which Franklin D. Roosevelt framed as a new social frontier, now that “the unlimited land of the old days … is gone.” By the time Grandin tracks the image to recent free trade debates (George H. W. Bush called trade zones a “revolution without borders”), this reviewer was more than persuaded.

When Grandin shifts from diagnosis to cure, something slips. Having bared the power of the myth and shown us the seductive force of its catchphrases, he takes up the metaphor himself. “The frontier is closed, the safety valve shut,” he writes. The answer now, he argues, is social democracy. But the fine history he has written suggests another question—not, what happens without the myth, but, what myth has replaced it?