Coronavirus in the Shadow of the Holocaust

When we look at the pandemic raging around us, do we really know what it is we’re witnessing?

This year, Israel’s Holocaust Remembrance Day fell on April 21, 2020. Since the Jewish calendar is lunar and observance starts on the evening before, the remembrance happened to fall—in a bitter irony too weird to be invented—on Hitler’s birthday. As the memorial siren wailed across Israel at 11 a.m., and many people all across the country stood up in silence to commemorate the millions of Jews exterminated during the Holocaust, the sense of mourning was diffuse. Because of the Covid-19 crisis, all memorializations were held online. As the two minutes of silent standing passed, I did something I’d never done before: rather than close my eyes and reflect inwardly, I kept my eyes open, raised my head, and looked around. I did not, as I usually do, try to imagine what it might have been like to live in the time of the Holocaust, when the presence of death was constant and human life had lost its basic value. Instead, I tried to imagine what it would be like if now, this reality, were itself a Holocaust in the making—if the reality we were now living had catastrophic proportions.

I don’t take full credit for the initiative. A few days earlier, my wife and I had watched Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018), a film based on Anna Seghers’s 1944 novel of the same name, transposing its action from the Nazi era into today’s world. It didn’t “invent” a Third World War, but rather set the events of the novel in present-day France, creating an eerily unsettling effect. Transit has none of the historical pathos that’s usually associated with Holocaust films—no Germans with stiff body language and wicked smiles listening to Mozart, or riding across Berlin in a vintage Mercedes-Benz, or shouting schnell at starving Jews. It was just a movie about people trying to flee before an unmarked army arrives and starts rounding everyone up for deportation.

Watching the film, I was reminded of Marvel’s What If comics, which I read as a kid, in which major plot-changing situations—like, “What if Spider-Man had joined the Fantastic Four” or “What if the Hulk had the brain of Bruce Banner” or “What if Spider-Man had rescued Gwen Stacy?”—were developed to their logical end. I tried to apply a similar transposition to today’s world, wondering what might have happened if Covid-19 had been allowed to run its course through the world population without any government taking any precautionary measures. I had read that about 60 percent of a given population pool was expected to be infected with the disease, and that, with a death rate of about one percent emerging in those countries that were aggressively testing and were transparent about their results—and taking the world’s population of 7.8 billion into account—we were looking at something like 46.8 million people dead. Even if the real toll turned out to be a quarter of this estimation, the number was sobering.

The idea isn’t to compare any of this to the Holocaust, which is something beyond anything ever perpetuated by anyone in history. But just as Albert Camus used the bubonic plague to portray the individual experience of what it was like to live in Nazi-occupied Paris, it’s possible to use other catastrophic events to help us understand the proportions of the danger we now face.

The pandemic is as close as anyone in the past three or four generations has gotten to a worldwide lockdown to save lives, forcing people everywhere to cope with the simultaneous threats of disease and poverty. Just before Holocaust Remembrance Day, I read an article that quoted an elderly Holocaust survivor as saying, “Be optimistic. No one is hitting you.” If you’re living in a time when you need a Holocaust survivor to tell you that things can always get worse, then you’re living in a pretty scary world.

I thought, too, of Aharon Appelfeld, the Israeli author and Holocaust survivor who spent much of his life depicting the emotions and sensations he experienced as a child trying to stay alive. Since a boy of eight doesn’t know that he’s living through a Holocaust, Appelfeld lacked any sense of historical consciousness about what was happening to him. All he knew was that he was cold, hungry, scared. He heard noises. He met other refugees in the forest. He found a berry bush, some edible roots, a field from which he managed to swipe some peas. Anyone can relate to these emotions and experiences, and this is the human thread that makes it possible for us to fathom the Holocaust in a limited way.

Another aspect of our association with the Holocaust during the Covid-19 crisis is that it’s the nightmare scenario we are trying to avoid. We’re not there. But we don’t know how or when it is going to end. We don’t know what influence it’s going to have on our global society. The 1918 flu pandemic had a much greater effect than we realize on world history. Gandhi led his nation to independence more than 30 years after recovering from the Bombay Fever. Hitler invaded Poland 20 years after the appearance of the flu epidemic, which hit the German army at a sensitive time and might have influenced the outcome of the Great War. And the Great Depression? Had the world not pulled its own financial rug from under its feet, militarization might not have had the appeal that it did, especially in Germany, and Hitler would have been just another quack political leader trying to rile up a society comfortable with its global lot.

In high school, I built a cardboard shanty for a report on the Great Depression, and also sang the Bing Crosby song “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime” (1932). I didn’t know then that the melody was written by Jay Gorney, a Jewish child survivor of the 1906 Bialystok pogrom, adapted from a lullaby sung to him by his mother. The song that calmed the child who’d witnessed the murder of Bialystok’s Jews, adults and children alike, was turned into a lament about the value of a coin—and human life—in times of extreme want. With the amount of homelessness I witnessed every day growing up in Los Angeles, I couldn’t imagine that the words of a beggar had been a national hit song—and even become the anthem of the Great Depression. I also couldn’t imagine a time when a dime meant life or death for a person who’d held a job for decades. Earlier this year, seeing the unemployment rate quintuple within a month’s time, I remembered that song, and saw that the value of what’s important to us can change in an instant. Gorney was 10 years old when his family, who’d gone into hiding during the pogrom, fled Bialystok and came to America. Everything they thought was important the night before the pogrom became less important than taking anything they could carry and moving halfway across the world. This, in itself, is proof of how quickly our realities can change—and how reality can put what we value into perspective.

We have tools today for dealing with cataclysmic disasters—or, more to the point, for working through major disruptions without letting them reach such cataclysmic proportions. Doing so involves the healthcare system, international trade, economic policy, as well as a myriad other worldly considerations. Yet when it comes to the processes that take place inside each of us separately but influence our reality as a collective, we need tools that help us understand what we are witnessing and to act in real time, while giving us the perspective that we often lack. And one of these tools is connecting to the spiritual layer of an upheaval such as the one we’re experiencing now. We may not yet see clear signs of this upheaval when we look outside our window. But we feel them when we try to do things the way we did them just a few months ago, finding that our patterns of behavior are totally out of whack with the reality in which we now find ourselves. I was speaking to a friend about people’s tendency to compare Covid-19 to the Holocaust. And although we can never really know what it was like to live during the time of the Holocaust, something she said suggested a Holocaust-like sensation: the feeling of having to be careful all the time, of being pursued or hunted, or of seeing the innocent around us dying unexpectedly.

The custom on Holocaust Remembrance Day in Israel is to watch films about the Second World War. This year, I decided to look up classic movies made in real time, or else in the immediate postwar period. I watched two: Night Train to Munich (1940), the first film to portray a Nazi concentration camp, and Distant Journey (1949), a Czech film that was censored due to Stalinist repressions. I was struck that both, each in its own way, dealt with the slow creep of Nazi terror, and how the horrible realities we now read about spread into people’s lives day by day, introduced by slight changes that didn’t seem dramatic when taken in isolation, but that became frighteningly radical when revealed in their broader context. It makes me wonder how Covid-19, together with the political exploitation of the crisis by governments everywhere, is changing what it means to be an individual in the world today.

We are all witnesses to the present crisis. But the thing about being a witness is that you don’t always know what you’re witnessing. Anne Frank didn’t know she was witnessing the Holocaust. She recorded her daily life, her thoughts and feelings, and only later, when reality played itself out, did the historical significance of her undertaking become clear. The difficulties of the present are many, and we’re not in a position yet to know their full extent. All we know is that things are changing. And that, if we don’t pay attention, we won’t know enough about our reality from just a few weeks ago to fully adapt to our reality a few weeks from now.

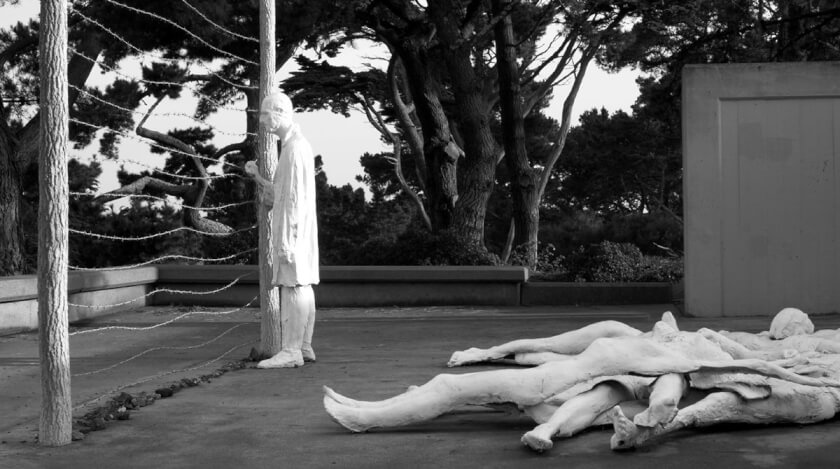

The seriousness of the situation comes from the deaths that have occurred—and that will likely continue to occur. The first to have died will be remembered most clearly. Others, who die once attention has moved elsewhere, will be lost in the total numbers. But the shock to our lives that we’ve already absorbed comes from a nightmare scenario that we are trying to avoid. We don’t want to see bodies piling up, mass graves in the hundreds of thousands, our streets full of untreated sick, a total deterioration of our social fabric, anarchy, chaos, exploitation, prejudice, or the collapse of healthcare. These social ills are threatening our reality at the best of times anyway. We don’t want to see the worst of humanity rising up. That was what we saw in the Holocaust.