Photographs by Ash Adams

I arrived in Homer, Alaska, just after the trees died. It was 1999. A string of warm summers had emboldened a tiny beetle that drilled into local spruce trees and killed them. The spruce bark beetle, which can pirouette on the point of a pin, leveled forests here across an area the size of Connecticut.

Old-timers who had lived in the woods for decades suddenly had extravagant mountain and ocean views. But now there was no privacy and more road noise. Some folks gave up on country life and moved to town. At the time, I couldn’t see the bigger picture. I noticed only that there was a lot of firewood around and that toppled trees left local trails impassable. I watched huge ships load spruce chips at the Homer harbor and then set off for Japan. I walked the beach, following a yellow tidal wrack of spilled chips.

The forests were only the first thing to suffer. Today, climate change is transforming Alaska from Panhandle to North Slope. No part of life is untouched.

Alaska is the nation’s frontline of climate change. The largest state in the union is warming twice as fast as the rest of the country. Spring comes earlier, winter arrives later, and some years it seems that winter does not arrive at all. Warming conditions have fueled wildfires and insect outbreaks. Sea ice is unreliable. Ocean acidification threatens to destroy the marine food chain, resources on which Alaskans depend. The state is melting, burning, and drying out.

Most Americans think that global warming will harm other people but not themselves. In Alaska, the consequences are already personal. Climate change affects how we live, how we work, how we think about the future, and what we put on the dinner table.

In Homer, we sit on a skinny band of coastline without the permafrost that cements the land in 80 percent of the state. Inland, warming temperatures are melting the permafrost, leaving the ground soupy and easily eroded. Structures built atop this once-solid foundation are toppling. Roads, pipelines, airports, and rail lines are also vulnerable, and climate change will add billions of dollars to the cost of maintaining our public facilities.

Two years ago, President Obama gazed out the window of Air Force One onto Kivalina, a tiny Native village on a wisp of land in the Arctic’s Chukchi Sea. Rising sea levels coupled with lack of sea ice and melting permafrost have left this community at the mercy of winter storms. Residents have decided to move, but funds to relocate the entire village don’t exist. Erosion threatens the survival of more than two dozen other communities here, with no clear solution.

Change has been a constant for Alaska’s Native peoples since Russian fur traders arrived nearly three centuries ago. Today, warming temperatures bring a new wave of consequences. Lack of reliable snow and ice cover can make subsistence hunting treacherous, if not impossible. The changing ocean conditions affect the availability of fish and marine mammal species that have been traditional food sources for generations. In rural Native villages, where groceries come long distances by air or sea and carry steep price tags, subsistence harvests amount to 275 pounds of wild foods per person each year. These essential natural resources are put at risk by the likely expansion of development and shipping into an increasingly ice-free Arctic. Although the state’s Native peoples have survived in the harshest of conditions for millennia, climate change means rapid, complex new challenges that will continue to appear for years to come.

Homer, at the end of the highway from Anchorage, has an advantage over the state’s many remote villages. But even though we live within a mile of a large grocery store, my family, like many Alaskans, relies on wild fish and game. Most nights we open our freezer to figure out what to make for dinner. My husband and I feel lucky to have a winter’s worth of salmon, halibut, and moose to feed ourselves and our two daughters. But any year now, we worry, could be the last of such richness.

When I first moved here, locals reminisced about the days when you could chuck a crab pot off the public dock and have a king crab dinner that night with all your friends. They gloated about the time when you could bring piles of shrimp from the bay into local bars. No more. These days, each season heralds a new loss. A leading climate scientist announced recently that the kind of mild, “winterless” winters we’ve been having lately—characterized by ice, broken bones, and frustrated skiers—will be the norm in about two decades. Two winters ago, common murres (penguinlike seabirds) washed up dead on local beaches, forming an endless black-and-white tidal wrack. Many scientists think a spike in ocean temperatures was to blame. For years we’ve planned family camping trips around clamming tides. Now we don’t dig clams and mussels, out of fear of paralytic shellfish poisoning caused by toxic algae that bloom in warmer waters. One bite can kill you.

The bad news is relentless. Moose-killing ticks are roving north toward Alaska from the Lower 48 and Canada as a result of milder conditions. The Eklutna Glacier, the primary drinking water source for Anchorage—the state’s population center—could melt away in as little as 50 years. And Denali National Park is trying to prepare for the landslides, floods, and wildfire smoke that climate change is likely to deliver.

All of this, occurring faster than many models predicted, is shaping how Alaskans think about their future. The state is expected to continue to warm quickly in the years to come, by two to four degrees Fahrenheit in the next three decades and as much as 12 degrees by the end of the century. Precipitation across the state is expected to increase even while much of the state dries out. Arctic summer sea ice will likely disappear by 2050, accelerating additional warming.

In this vast and politically conservative state, concern about climate change transcends political, cultural, and socioeconomic lines. Most Alaskans—about 75 percent in a recent survey—are worried.

People all over the world have seen images of Alaska’s crumbling coastal villages and melting glaciers. But fewer people know about the eroding ways of life across the state, the lives altered by warming temperatures, the anxiety over what’s to come. Fewer people have heard the workaday stories of the nation’s rapidly changing North, the voices that don’t often make headlines.

I wanted to know what other women were thinking about these changes. What does climate change mean for their families? Their homes? Their work? Their vision of the future? Their world is in flux—but the changes they see are harbingers of what’s to come for us all.

Paula Evans, 11, and her mother, Ann, on the reef at low tide in Nanwalek, where they regularly harvest traditional foods (Ash Adams)

Paula Evans, 11, and her mother, Ann, on the reef at low tide in Nanwalek, where they regularly harvest traditional foods (Ash Adams)

Ann lives in Nanwalek, a Sugpiaq Alutiiq community of about 250 people at the edge of the Gulf of Alaska. No roads lead to the village, which occupies a spruce-strewn hill above a beach and gravel airstrip where tiny planes land next to an unassuming shack: the terminal. During a minus tide, for a few hours, a hump of black rocks emerges from the sea just off the beach.

A mother of three and the Nanwalek school secretary, Ann is an avid subsistence harvester and one of a few village residents who regularly collect octopus, something she learned from elders 25 years ago. During low tides, in addition to octopus, she gathers other traditional foods: seaweed, marine snails, fish eggs, and bidarkis—a type of tidal pool invertebrate with a single sneaker-shaped shell and bright orange flesh that clamps tightly onto rocks. Bidarkis are special, Ann says. “They’re really fresh, really sea.”

At the one-room grocery store just up from the beach, a gallon of milk costs $11, and tired heads of iceberg—$2.75 a piece—come in only once a week. In the spring and summer, Ann harvests fiddlehead ferns, wild chives, a marsh plant called goose tongue, and the pungent celerylike stalk of pushki, a local wildflower.

Ann’s son, Evan, 16, gobbles dried halibut like it’s candy. Tessie, 13, gorges on spring seaweed. Her youngest child, Paula, 11, prefers her octopus pickled. Ann likes to boil bidarkis in salted water and make them into gravy. Her husband, Tommy, loves a rice bowl topped with traditional foods—bidarkis, octopus, seaweed, salmon eggs, smoked fish, and onions—and drizzled with seal oil.

Ann’s ancestors harvested from these shores for thousands of years. In addition to filling the dinner plate, traditional foods link Ann and her family to their culture and its deep past. They are a lifeline across generations shaped by dramatic and often violent change. When Russians arrived in the 18th century to hunt sea otters, they brought disease and alcohol and coerced Native men to do the hunting for them. Ann’s village—once a seasonal camp—became a year-round fur-trading depot and then the site of a salmon cannery. Nomadic life became sedentary. Village residents now have trucks, Internet connections, and cell phones. But the kids who have left the village for school or work still call home, begging for someone to send them bidarkis. “Even though they’re living in the city, they still crave our Native foods,” Ann says.

The cannery has been gone for decades, but change is the mainstay of life here. When you eat out of the sea and off the land beyond your doorstep, you notice the changes. Octopus may be plentiful, but bidarkis are scarce and smaller than they used to be. There didn’t seem to be as many pink salmon running into the lagoon at the edge of the village last summer, Ann noticed. Sea urchins, crabs, shrimp, and clams are harder to find. Weather in the village is different than when Ann was a kid—more lightning storms, less snow. Winters are mild, not like when Ann was young and the cold air would freeze your nose hairs.

Ann is worried. As the marine resources shift around her, she wonders whether she’ll be able to continue harvesting, whether her children will be able to keep that connection to their culture and past. “To me,” Ann says, “subsistence is a way of life. It’s not just fishing. It’s not just picking. It’s not just gathering.”

During the dead of winter, Bree Hoerdeman works as a trapper; come February, she is the foreman of a crew fighting wildfires. (Ash Adams)

During the dead of winter, Bree Hoerdeman works as a trapper; come February, she is the foreman of a crew fighting wildfires. (Ash Adams)

Those dark winter days are marked by chores: feed the dogs that make up two sled teams, haul water from the river, melt snow, split firewood. Then take off with the dogs to check traps along the 100 miles of trail they maintain across open country interrupted only by stands of spruce and the channels of rivers. There are no roads, no power lines. There is no one else around.

In the evening, they tune an AM radio to a program from 200 miles away that sends messages to trappers scattered across this remote country: a nephew just born, a call-back needed from a summertime employer, a friend from upriver checking in to make sure everything is okay.

A trapper’s life depends on the cold. But winters in Alaska have warmed by nearly seven degrees since reliable records first started in 1949. That means Bree and Heath can’t trust rivers and streams, which have always served as roads and trails in winter. During sudden midwinter thaws, which are more frequent now, their traps slick over with ice and become useless.

“We’re wondering: what if the rivers don’t freeze anymore?” Bree asks herself again and again. “What if we can’t run the dogs anymore? What if winters keep getting warmer and warmer?”

Trapping season ends in February, which is when the couple emerges from the backcountry and Bree shows up for the other half of her life as the foreman of a 22-person crew of hotshots, the most expert wildland firefighters in the industry. She’s responsible for the safety of her team.

Warming temperatures mean job security for people who work wildfires in Alaska. The wildfire season is getting longer, with fires erupting in early spring and lasting later in the fall than usual. Two years ago, a wildfire broke out in October, weeks after crews had been laid off for the year and fire equipment put away and winterized. Wildfires are raging in Arctic tundra, a habitat typically too cold and wet to burn. Fires are reappearing in areas already burned—previously considered safety zones for fire crews to set up camp—likely a testament to the warmer, drier conditions. And fires in thousand-year-old peat bogs, now drying out as temperatures rise, can burn underground all winter long, only to erupt again in the spring.

Wildfire is both a symptom and a driver of climate change. Bree knows this. Fires release carbon long trapped in soils and plants, which drives more warming. A decade ago, a single tundra wildfire on Alaska’s North Slope released as much carbon as had been stored by all tundra regions across the Arctic in the previous quarter century. Wildfires are expected to burn twice as many acres in Alaska by 2050.

Bree knows there will be a fire job for her for the foreseeable future, but her heart lies in the bush, in her trapping life, in those dark days of chores along those 100 quiet miles. Her heart lies in the cold.

Now the owner of her own boat, Hannah Heimbuch first worked in the commercial fishing industry on her parents’ skiff when she was a girl. (Ash Adams)

Now the owner of her own boat, Hannah Heimbuch first worked in the commercial fishing industry on her parents’ skiff when she was a girl. (Ash Adams)

Hannah’s first job in Alaska’s commercial fishing industry was to count salmon that came over the gunnel of her parents’ setnet skiff. She was five. Then she worked as a deck hand for nine years. Now, at 32, she’s worrying over a list of 30-odd fix-its to take care of on her own boat. The reel that needs to be expanded to fit more net. The zincs to be replaced. The zerks to be greased. Not to mention that the forecasts for the Cook Inlet sockeye salmon haven’t been particularly rosy.

An undercurrent to all of this is what Hannah calls the “macro anxiety” of her life: climate change. “There’s just this nervousness,” she explains. “Am I going to be able to adapt to whatever change comes my way?”

To be a fisherman has always meant living at the whim of the sea. Salmon runs naturally fluctuate. Storms and tides dictate when and where you fish. Sometimes a whale gobbles up your catch before you can land it.

But climate change is different. Warming temperatures and changing ocean conditions could upend the lives of fishermen in Alaska—and across the world. Already, global oceans have become 30 percent more acidic as seawater absorbs increasing amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The cold and relatively less salty waters of the North Pacific are particularly susceptible to ocean acidification, and current projections see a continued and rapid decrease of pH in Alaska’s coastal waters. Scientists predict that by the end of the century, the ocean environment will be more acidic than it has been in the past 20 million years. Acid makes it difficult for organisms to build shells and other hard body parts. In the souring seas, some tiny shelled organisms that make up the base of the food chain for salmon and other marine life simply dissolve.

The changing chemistry of the ocean is not abstract to Hannah. She has a boat payment to make, a student loan to repay.

Across Alaska, there’s a $6 billion economy at stake, one that employs tens of thousands of people. More than half the nation’s commercial seafood harvest is at risk. Also on the line is the survival of scores of coastal communities dependent on the fishing industry, and the very character of the state itself.

Alaska’s commercial fisheries harvest more than 40 species of marine life, and fishermen and researchers believe it’s only a matter of time before the industry suffers a catastrophe. Already, the world is looking different to people who live on or by the ocean. They’re seeing warm-water species appear off Alaska’s shores. Oyster farmers are having a hard time getting spat—the small larvae used to start a crop—because their sources are affected by acidification. Lucrative crab and pollock industries are expected to face declines with further acidification and warming. Uncertainties swirl around salmon, which are notoriously sensitive to water temperature.

Hannah is figuring out how she’ll stay afloat if the salmon run fails. Anywhere from a quarter to half her annual income comes from fishing, and she aims to grow the business. For now, she spends her off-seasons as a writer advocating for sustainable fisheries.

Hannah’s new boat came with the name Salmon Slut, and she’s not changing it. She knows she’s adding to a long tradition of tacky boat names. With so many serious questions confronting the fishing industry, a little humor doesn’t hurt.

Lilli Johnson didn’t learn much about climate change in high school, but she intends to study it, along with public health, in college. (Ash Adams)

Lilli Johnson didn’t learn much about climate change in high school, but she intends to study it, along with public health, in college. (Ash Adams)

Lilli’s first winter in Alaska, when she was only six, was hard. She and her mother had moved from Los Angeles with no idea about how to dress for the cold. So they layered socks inside Lilli’s rubber boots. But her feet still froze. “There’s winter boots? That’s a thing?” Lilli remembers both of them realizing that winter.

Lilli took a gap year after graduating from high school. But not to goof off. She worked at a primary school in rural Uganda, where the language barrier didn’t prevent her from connecting with the kids.

Lilli would pull out photos from home to show the children, many of whom knew nothing about snow. No one knew anything about Alaska either. When she described her home state, she found herself talking about climate change. This baffled the people around her. They didn’t know about climate change. Lilli was surprised—warming temperatures have parched Uganda and the surrounding region, sending hundreds of thousands of people from their homes as refugees of drought and war. “How are they going to know how to help themselves when they don’t know what the problem is?” Lilli wonders.

Lilli is a climate change “native”: the omnipresence of the problem has shaped her life, without her really noticing. For most of her life, she didn’t think that much about it, even when she and her friends would hike to the glacier Lilli sees through the windows of her house. They looked back on photos from the same hike two years before and could see that the ice had retreated up the valley. When she glimpsed a photo of the same spot from 20 years ago, she was astounded.

“For a while it was like, ‘Something’s going to happen but not in my lifetime.’ And now it’s starting to be more, ‘It could be pretty soon that major changes start to take effect,’ ” Lilli says.

Lilli sees that people in charge are not acting quickly or strongly enough to halt climate change. “It’s so frustrating,” she says. “And they say that young people don’t do anything and are on their phones all day.” She thinks future generations will look back on the current response to the threat with horror, in the same way that we regard slavery and child labor today. Like us, they will wonder: “Why did they let that happen?”

She describes herself as more optimistic than pessimistic when it comes to climate change, but not by much. She places herself as a “strong six” on a one-to-10 scale between deep despair and wild hope. Lilli is in her first year at Hampshire College, where she’ll devise her own curriculum. She plans to study public health, a field that she believes is intertwined with climate change and social justice. Despite these plans, it’s impossible for Lilli to imagine her life in the decades to come. At noon, she’s not even sure what she’s going to have for lunch. But Lilli is confident about seeing what the world might need of her, and what it is she can give.

Dawn Magness collects field samples in the Kenai Wildlife Refuge, where she is a landscape ecologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Ash Adams)

Dawn Magness collects field samples in the Kenai Wildlife Refuge, where she is a landscape ecologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Ash Adams)

Dawn entered the field of ecology as someone who had always been more interested in animals than people. As a kid, she had a dog for an imaginary friend, and when the family finally got a real dog, Dawn preferred the husky’s company to a boisterous birthday party or crowded playground. When she found out she could get paid to be outside with animals, she got a job as a field assistant, then as a biological science technician and field biologist, which led to seven years spent banding birds across Alaska and as far away as Saipan, skiing in search of weasel-like fishers in Idaho, and trapping pine martens using chicken gizzards and jam. Eventually, she decided to pursue an advanced degree.

Dawn helps conserve biodiversity within the refuge, a canary closely watched for the effects of climate change. Here, young spruce trees are barging in on thousand-year-old peat bogs and migrating up the otherwise treeless slopes of snowcapped mountains. The region’s characteristic kettle ponds—small lakes formed by glacial deposits—are drying up. Forests beset by drought, insect infestations, and wildfires, all brought on by warming temperatures, are giving way to grasslands.

Climate change is turning her mission on its head. “Most conservation is based on what was there when Europeans arrived,” Dawn explains. But with rapid warming, historical conditions will not return.

Dawn is 44 and the mother of a nine-year-old son. On her time off, the two of them go into the refuge to listen to the melancholy “oh-dear-me” song of golden-crowned sparrows or hike to Upper Fuller Lake, where grayling dapple the surface as they feed.

“Climate change has really shifted how I think about ecology,” Dawn says. There’s no going back to projects that aren’t tied to people. “I think this luxury of not engaging is over,” she says. “Now I think more about human rights and social justice and how we integrate those things.”

As warming temperatures make life inhospitable for some of the refuge’s species— which will die off, march north, or seek higher, cooler elevations—should new species be introduced that are better suited to the altered conditions? Bison, for example, could roam the new grasslands that warming temperatures seem to favor. They could provide hunting opportunities and, by grazing the vegetation, reduce fire risk to nearby communities. But some biologists argue it’s dangerous to mess around with nature. Today, the very climate isn’t natural anymore.

Dawn trained for 12 years to be an ecologist, studying how organisms relate to their environment, how to design field experiments, and how to perform complex statistical analyses. But as the environment around her transforms, the toughest questions she faces now are ethical. What are our responsibilities to our children? To our planet? “How much should we be shaping the future?” Dawn asks.

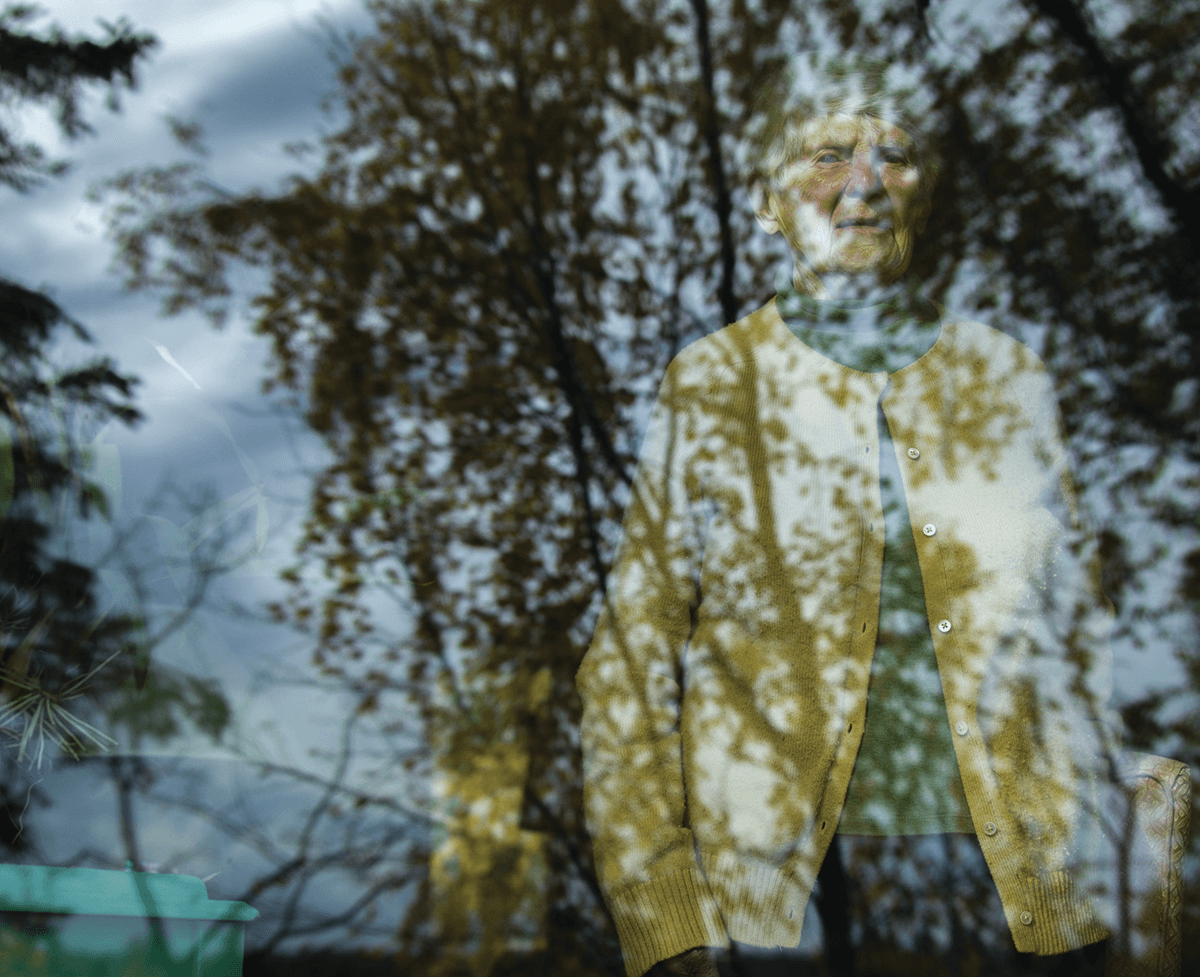

Marge Mullen has lived on the same plot of land for seven decades. She moved to Soldotna with her then-husband from Chicago. (Ash Adams)

Marge Mullen has lived on the same plot of land for seven decades. She moved to Soldotna with her then-husband from Chicago. (Ash Adams)

Two years earlier, Marge and her husband Frank had read an article in the Chicago Tribune about all the undeveloped acres in Alaska waiting for homesteaders. Having grown up the oldest of six children in an apartment building so close to its neighbor you could pass a broomstick between the windows, Marge was eager for the space and the adventure. She and Frank bought 100 acres along the Kenai, a glacier-fed river full of dust the ice had scraped off mountains, which turned it a milky turquoise.

This was wilderness. No electricity. No plumbing. There were only a dozen or so other settlers around. The couple had no idea that the river would become one of Alaska’s most important salmon fisheries and the state’s most popular spot for anglers.

Frank was often away working at salmon canneries or as a longshoreman, leaving Marge alone in the woods in their 14-by-16-foot cottonwood pole cabin with two, three, and then four children. “I had to find out how much courage I really had,” Marge says. The river was the center of life. The family fished for salmon and trout, and Marge put up as many cases of fish as she could store. When her son discovered a school of silver, blade-shaped fish one spring day, he didn’t have a bucket, so he slipped them down his pants and trudged the loot home. These were hooligan, an oily fish that was delicious when fried or baked and provided a welcome break from salmon.

In the fall, Marge and her children listened to the sounds of the river freezing up—the clinking of ice chunks as they banged against each other until they became a solid jumble of ice, bank to bank. The Kenai would be frozen for months. These days, some winters it never freezes.

Marge, now 97, has lived on the same patch of land along the Kenai River for seven decades and witnessed many changes. When she first moved to its banks, there were no boats on the river, no weekend fishermen, no tourists. Today, the river generates hundreds of millions of dollars in economic activity. Soldotna, the town where Marge lives, was too small to show up on the 1950 census; now it is a strip-mall hub at the intersection of two highways. The population in the area is about 37,000. Growth has exploded here, but it’s warming temperatures that worry Marge.

“My main source of protein is threatened,” she says. Marge, now divorced, lives with her eldest daughter in a small, modern house so close to the river, you could chuck a fish head out the kitchen window over the bank. They eat salmon three times a week. “We rely on it.”

The world outside their windows is changing. The Kenai is running higher—likely because of increased glacial melt—and it’s running warmer, a trend that could be lethal for salmon. Warmer water makes salmon more susceptible to disease. Already the river’s king salmon—another canary in these changing conditions—are smaller and harder to come by. In the decades to come, streams in the region that aren’t fed by glaciers will likely heat up beyond the point at which salmon can survive.

In seven decades, Marge’s world has gone from wilderness to the woods behind Walgreens. A life once characterized by bounty has tallied up more than its share of loss: her marriage; her son, Frank Jr., a commercial fisherman who died recently of cancer; and now all of the pieces of her life at risk from warming temperatures. A bucket of wild cranberries that Marge’s daughter Peggy picked last fall sits in the cool entry to their house. Peggy likes to harvest more than she can use in a single year just in case the crop fails, an increasing worry these days. Those bright red berries are part omen, part wish.

We are so lucky, I often think, to live here in Alaska. We are not living under a scrap of tarp amid rising floodwaters in Bangladesh. We are not fleeing drought in Central Africa. We know where our next meal comes from. Our taps run with drinking water. And yet, for us, too, this time is characterized by climate change—and by the uncertainties that this change means for our future.

I found myself feeling a kinship that went well beyond gender as I interviewed the women for this project. I imagine all of us looking back on this time. How will it seem to us decades from now? That we lived in relative bliss? That we ambled through our days innocent of what was to come? That we were all wrong?

What I do know is that the world around us is changing, and quickly. I think about the riverbank Marge moved to 70 years ago and the tiny coastal villages where Ann’s grandparents lived. Those places are long gone now, and they are never coming back. What around me today will disappear?

My daughters are five and eight years old. Their world is static and bountiful. Outside, there is ample raw material to build forts, make fires, and create fairy houses. Their lives are crowded with the diverse characters of this wild place: jellyfish and magpies, sea otters and moose, humpback whales and sandhill cranes. Their years are a bundle of things to look forward to: summer weeks at fish camp, blueberry season, the first snow. As I contemplate the changes we’ve already seen as well as what lies ahead, what I feel most fiercely is that I don’t want their lives to be characterized by loss.

This piece was funded in part by a grant from the EPSCoR program at the University of Alaska.