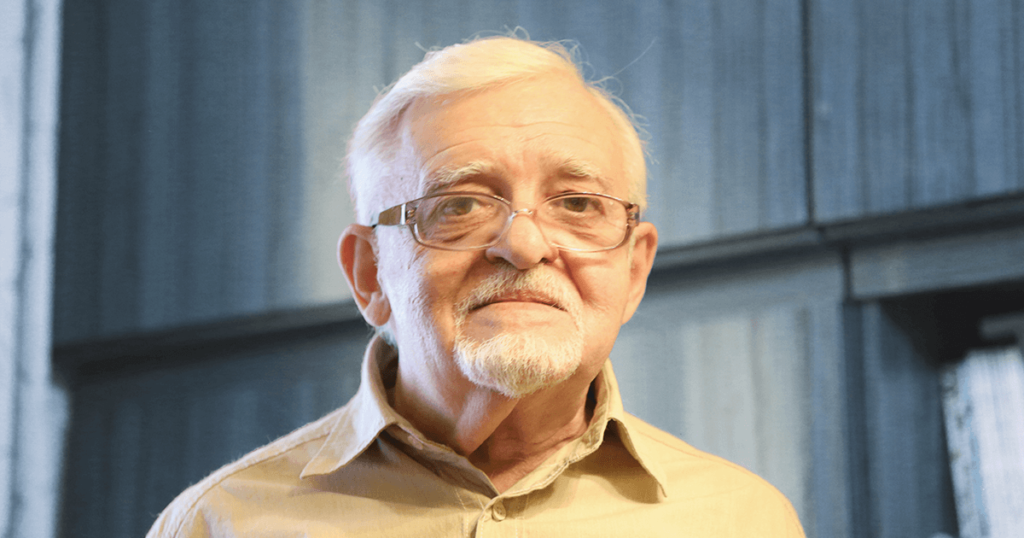

Nikolai Kapustin’s name is largely unknown, though he is not only a virtuoso pianist trained in the grand Russian tradition but also a prolific composer. His pieces bear such titles as Sonata, Prelude, Fugue, and Bagatelle, yet his music has far less in common with Chopin or Bach than with Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, and Duke Ellington. Now 80 years old, Kapustin is a resident of Moscow and leaves the city only once a year, to visit his summer home some 60 miles away. If ever the term cult figure applied to a musician, it’s to him—his following is loyal and fanatical—but I confess that I hadn’t heard of Kapustin until Monday night, when the Korean pianist Dasol Kim concluded his Washington recital with two of the composer’s Eight Concert Études, op. 40. The jazz-inflected etudes that I heard (Nos. 7 and 8) were beguiling, exuberant pieces, which Kim performed with great panache and skill. So intriguing were those works that I left desperate to hear the entire set of eight. Indeed, I heard many patrons in the lobby and the elevator afterward asking, “Do you know who that composer is?” Each time, the answer was some variant of, “No, but I want to hear more.”

Kapustin was born in eastern Ukraine in 1937. With his father fighting in the Second World War and with daily life under German occupation increasingly perilous, his mother and grandmother took him and his sister to live in the Kyrgyz city of Tokmak. He was four years old at the time. A decade later, the family (now reunited) moved to Moscow, where Kapustin, a precocious musical talent, began piano lessons with Avrelian Rubakh. During the years 1954 and 1955, Kapustin discovered jazz, listening to nighttime broadcasts of Voice of America that introduced him to the likes of Benny Goodman, Nat King Cole, and Louis Armstrong. Rubakh, while honing the young man’s formidable technique, also nurtured this nascent interest in jazz—he was, in this sense, not only a formative influence but the ideal teacher at that particular moment. In the age of Stalin, we shouldn’t forget, jazz had been officially denounced as a supreme expression of capitalist decadence. To listen to it, let alone play it, was an act of bravery and defiance. Stalin’s death in 1953 didn’t exactly liberate the art form, yet slowly, the proscriptions were relaxed, and musicians began to feel more confident expressing themselves in public. Kapustin’s gigs with a jazz quintet included a monthly engagement at an upscale Moscow restaurant.

In 1956, Kapustin entered the Moscow Conservatory and was accepted into the class of Alexander Goldenweiser, who had instructed Lazar Berman, Grigory Ginzburg, and Tatiana Nikolaeva, among other 20th-century titans of the keyboard. Goldenweiser, however, was in his 80s at the time, and ultimately had little left to give, pedagogically speaking. Still, the young artist thrived at the conservatory, and his graduation recital included Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 2, one of the most fiendishly difficult pieces in the repertoire. Meanwhile, Kapustin was continuing to teach himself how to compose—a jazzy Concertino for Piano and Orchestra, which he was able to perform in public, became his opus 1.

During the height of the Cold War, jazz (and really, all things American) began to be fashionable among a certain segment of Soviet youth, and even though some risk still remained, it was now possible for Kapustin to embark on a life as a jazz musician. He toured with a big band, arranged the music of Count Basie and others, performed for television and radio, and made recordings for the movies—work that sustained him throughout the 1970s. All the while, he wrote his own pieces, and in the 1980s, he devoted himself full-time to composition. Although he has written music (161 works to date) for all kinds of ensembles large and small, the core of his output consists of his highly syncopated, virtuosic compositions for solo piano. He has recorded much of this music, though his growing popularity in the West today has much to do, as well, with pianists such as Steven Osborne and Marc-André Hamelin championing his work.

I’ve now had a chance to listen to all of Kapustin’s Eight Concert Études, written in 1984, just before the full flourishing of glasnost and perestroika. Each of the etudes is as seductive as the two I heard Monday night. The first is a roiling, jubilant romp, the sixth more playful and slyly humorous. All of the pieces are rhythmically driven, though the eighth etude is perhaps the most relentless, the fleet figures spinning out in wild cascades, up and down the keyboard. The seventh etude conjures up, at first, a warm and languid summer’s day, the music soon picking up in intensity and speed as it heads toward a Gershwin-esque climax. Several of the etudes, moreover, include moments of homage to the classical masters: the shimmering second calls to mind Liszt’s Transcendental Études; the sharp and angular third is a play on Schumann’s notorious, finger-breaking Toccata; and the dreamy, wistful fourth bears the faintest imprint of Rachmaninov.

The word étude means “study,” though in the Romantic age and after, the greatest examples of the genre, composed by Chopin, Liszt, Debussy, and Ligeti, weren’t just vehicles for working a pianist’s muscles or refining a particular technique, but were also moving works of art, polished miniatures that could communicate a wide range of emotions. Kapustin’s etudes do precisely that. What I find brilliantly disconcerting about them (and about the Chopin-inspired 24 Preludes in Jazz Style, op. 53, which I devoured the other night) is that they seem improvised, even though I know that every note has been written down, every dynamic notated. Kapustin has spent much of his life improvising at the piano, and yet his compositions are beholden to classical modes and structures. After all, it would be impossible, as he has said before, to improvise sonata form. As a result, Kapustin’s scores contain an inherent tension. They aren’t really jazz, and they aren’t exactly classical. They aren’t examples of fusion either, at least not in the way that Ravel’s bluesy Violin Sonata No. 2 fuses disparate idioms. Perhaps this music defies categorization. And maybe what you call it isn’t all that important. Simply listen to a few infectious, delightful bars, and you’ll likely want to hear a good deal more.

Listen to Marc-André Hamelin perform the last of Nikolai Kapustin’s Eight Concert Études: