Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune, by John Merriman, Basic Books, 308 pp., $29.99

Transitory, confusing, hopeless, the Paris Commune of 1871 is easily ignored or misunderstood. The title of John Merriman’s new book gets right to the point he wants us to remember: that it ended in an orchestrated genocide. Soldiers slaughtered tens of thousands of Parisians, both combatants and civilians, while the rest of France looked away or cheered the killers on.

The Commune’s misbegotten spasm of early people power lasted just 64 days and occurred in the political and social vacuum left by three successive French humiliations—the catastrophic Franco-Prussian War, the crushing Siege of Paris, and the ignominious dissolution of Napoleon III’s Second Empire.

When the siege ended, in January 1871, with the French government’s capitulation, better-off Parisians in the central and western parts of the city sought to shake the blues by reverting to habits of prewar gaiety, jamming the brasseries, departments stores, and boulevards.

In the northern and northeastern arrondissements, meanwhile, a miserable population seethed in crowded slums. The building of Haussmann’s Paris that so dazzled the world had drawn cheap labor in quantity from the provinces and beyond. Many of these people were now out of work. The war had brought refugees to join them. Their suffering was acute, their anger directed at the business classes, the political leadership, and the Catholic clergy. It boiled over almost overnight.

“Never has a revolution so surprised revolutionaries,” proclaimed one of its heroines and victims (by imprisonment), Louise Michel. Repulsing the regular army, itself exhausted from war, the communards seized artillery emplacements located on the city’s highest elevation, Montmartre. Adolphe Thiers, head of the provisional postwar government of France, withdrew his military forces, and also the bureaucracy, even police and magistrates, from the capital. As he reopened a rump national government in nearby Versailles, an address with uncomfortable symbolism, the communards were surprised to find themselves, at least nominally, governing Paris.

The Commune began, Merriman writes, as “something of a ‘permanent feast’ of ordinary people who celebrated their freedom by appropriating the streets and squares of Paris. Revolutionary songs echoed, well entrenched in the collective memory” of the French Revolution 82 years earlier, and two other revolutions since. Ninety newspapers appeared in the Commune’s short life, along with hundreds of manifestos, posters, and handbills proclaiming the new world order. The communards were disputatious and disorganized on just about every level. They banked their fantastic hopes against the Army of Versailles on sloppily armed and poorly commanded paramilitaries. It was government by civics class and rally.

The Commune promulgated new laws helter-skelter. A piquant example: the abolition of night baking by decree on April 20—to lift the “nighttime enslavement” of bakers benefiting “the aristocracy of the belly.” The problem was that Parisians of all classes insisted on warm bread in the morning. The decree, as were so many, was unenforceable.

Anticlericalism suffused the revolutionary fervor. On Palm Sunday, church and state were separated by decree—one of the Commune’s impulses that eventually, 30 years later, became French law. The most notorious blot on the Commune came in its mad final days with the kidnapping and execution of the Catholic archbishop of Paris, Georges Darboy. His martyrdom helped to rationalize the massacre that followed.

During April and May, the walls of Paris were sealed. The Army of Versailles controlled the southern and western sides; the victorious Prussian forces, which remained in France under the terms of the humiliating armistice, constituted an effective wall to the north and east. Their presence made Thiers’s military task, once he had rallied his army, much simpler.

Merriman suggests that the military incursion would not have been possible had the communards not been objectified by French society. The whole of France, not just the rebellious quarters of Paris, had been demoralized by the war and was eager for scapegoats. Théophile Gautier, the otherwise distinguished French writer, called the communards “savages, a ring through their noses, tattooed in red, dancing a scalp dance on the smoking debris of society.” Le Figaro spoke for many in urging Thiers to take action. “Never has such an opportunity presented itself to cure Paris of the moral gangrene which has eaten away at it for the last twenty years. … Today, clemency would be completely crazy … Let’s go, honnêtes gens! Help us finish with the democratic and socialist vermin.” The New York Herald seconded the motion. “Root them out, destroy them utterly, M. Thiers, if you would save France. No mistaken humanity.”

They needn’t have worried. Paris, Thiers baldly said, merited “a considerable, rapid massacre,” and so it came to pass. La Semaine sanglante, or Bloody Week, began on May 21, as tens of thousands of troops entered the city. Gaston Galliffet, the decorated French general who a few days later would lead the massacre of untold numbers of prisoners in the Bois de Boulogne, declared: “I am Galliffet! People of Montmartre, you think me a cruel man. You’re going to find out I am much crueler that even you imagined!”

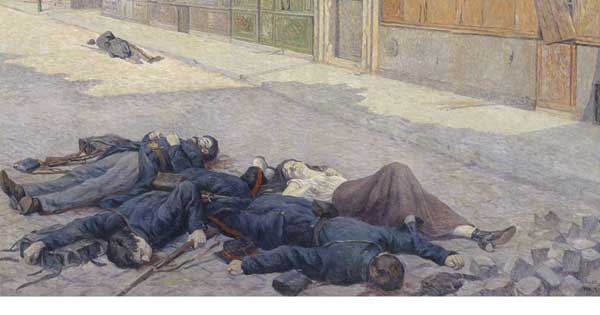

Even in districts not known as hotbeds, soldiers shot people they encountered nearly at random—for being in the wrong place, for dressing the wrong way, for saying the wrong thing. One way to tell whether you might have a communard in custody was to check the skin on his shoulder. If it was bruised, it meant the sharp recoils of a rifle, which was grounds for immediate execution. Bodies accumulated on the streets in massive heaps.

Even in districts not known as hotbeds, soldiers shot people they encountered nearly at random—for being in the wrong place, for dressing the wrong way, for saying the wrong thing. One way to tell whether you might have a communard in custody was to check the skin on his shoulder. If it was bruised, it meant the sharp recoils of a rifle, which was grounds for immediate execution. Bodies accumulated on the streets in massive heaps.

The stupefying rampage took as many as 20,000 lives, and maybe many more—historians still differ. “The capital had seen nothing like it since the Saint Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572, when Catholics had slaughtered Protestants.” In scale, the author observes, nothing would come close to the slaughter until the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

Merriman, a distinguished scholar of France at Yale, does not preach or fulminate about this regressive episode. The facts are powerful enough. But neither does he mince words about what the Commune meant for the French republic that succeeded it:

The power of the centralized French state endured, as did its capacity for extreme violence, in France and in its colonies. If the Paris Commune of 1871 may be seen as the last of the nineteenth-century revolutions, the murderous, systematic, state repression that followed helped unleash the demons of the twentieth century. This is sadly perhaps a greater legacy of the Paris Commune than the experience of a movement for freedom undertaken by ordinary people.