Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin; Liveright, 624 pp., $35

Shirley Jackson used to joke that she was a witch—she even laughingly took credit for breaking Alfred Knopf’s leg in a Vermont skiing accident after the publisher refused to increase a book advance for her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman. She had to wait for Knopf to leave New York, she said, since she lived in Vermont and witchcraft couldn’t be legally practiced across state lines. As writer and critic Ruth Franklin explains in her excellent new biography, Jackson was indeed a student of witchcraft, a tarot card reader, and someone influenced by Sir James George Frazer’s study of myth, The Golden Bough.

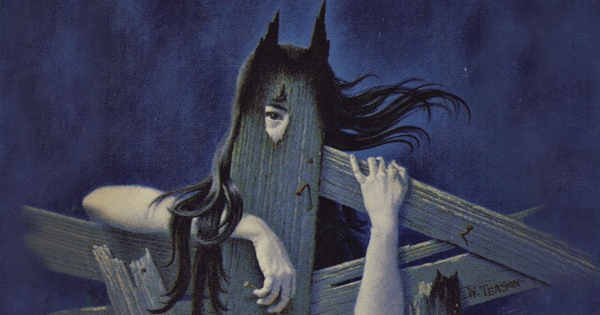

But she was most of all a witch in her writing, in her scary ability to see into the dark places of the human soul and in the spells she cast on enthralled readers. Every Shirley Jackson sentence is a little work of art. “The morning of June 27th was clear and sunny, with the fresh warmth of a full-summer day,” begins her most famous and most haunting story, “The Lottery.” The real magic of Shirley Jackson is the way she used a little bit of paper and ink to create scenes that make you gasp, send chills of recognition down your spine, and give a sinister cast to the light in the room where you are reading.

Jackson was the best-selling and award-winning author of six novels, five collections of short stories, two comic memoirs, magazine articles for The New Yorker, and a how-to book about being a mother titled Special Delivery. Influenced by Hawthorne, Poe, and Henry James, she has been an acknowledged influence on Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, and Joyce Carol Oates, among many others. In most of Jackson’s work, the source of horror is not a spooky outside force, a dead relative, or an evil spirit; Jackson’s horror comes from women’s lives, from their powerlessness and their resulting fury. As Franklin writes, “Two decades before the women’s movement ignited, Jackson’s early stories were already exploring the unmarried woman’s desperate isolation in a society where a husband was essential for social acceptance.”

There were at least two Shirley Jacksons, the brooding witch of her fiction and the jolly domestic goddess of her nonfiction. She was a terrific, dedicated mother—a woman who wrote brilliant stories as she baked Christmas cookies or jotted notes for a novel while her kids sat down to eat the lunch she had prepared. She often said that her life was saved by the birth of her children. But in Franklin’s telling, Jackson’s life is a marital horror story, an American gothic of the mid-20th century, playing itself out in the decades after women won the right to vote.

Jackson was not immune to the pressures on women in the 1940s. She lied about her age to make it seem that she was as young as her husband, the first of many accommodations to a man who would dominate her life. Jackson was paid less for her work than men. (Franklin uses my father, John Cheever, as an example of someone who was paid more than Jackson at The New Yorker. He was, but still far less than many other writers.) Severe financial pressures clouded her early years as a wife and mother—pressures that changed and intensified as she began earning more than her husband, a well-respected teacher at Bennington College whose salary was apparently not enough to support his family.

Born in 1916 to prosperous, distinguished parents in the tony suburbs south of San Francisco, Jackson grew up in a comfortable household, but her parents were socially demanding, setting standards that she could not possibly uphold. Jackson’s father, a businessman, was distant and critical. But her socialite mother was always Jackson’s most severe critic, frequently expressing intense disappointment, especially as Jackson’s weight fluctuated and her looks failed to conform to a blond, American Beauty ideal. Jackson took refuge in reading and writing, activities her mother disapproved of. When Jackson was the subject of a flattering Time magazine story in 1962, her mother told her that the photograph made her look fat.

Jackson’s marriage to Hyman, a brilliant, sexually driven critic, was the best thing in her life and the worst. He adored her and understood her literary gift, perhaps better than she did. But he believed in sexual freedom, and his constant philandering—the neighbor, students, Jackson’s younger best friend—was heartbreaking. Hangsaman, Jackson’s 1951 novel about a student who becomes lost in many ways while attending a Bennington-like college, is, according to Franklin, “unmistakably a document of Jackson’s rage at her husband.”

Although Hyman theoretically granted his wife the same sexual freedom he claimed, an overweight woman raising four children had no opportunities to stray even if she had wanted to. By the 1960s, when Jackson was in her 40s, her efforts to lose weight through liberally prescribed drugs caused a series of psychological and physical health crises. She was often afraid to leave the house. She died in 1965, at the age of 48, of cardiac arrest during her afternoon nap on the sofa in their house in North Bennington, Vermont.

Franklin has written a gripping and seductive story that is as compelling as it is accurate. In telling it, she enjoyed the cooperation of Jackson’s four children, as well as that of Phoebe Pettingell, the Bennington student Hyman married soon after Jackson’s death. She also made use of archival letters, stories, and journals that were undiscovered or unavailable at the time of Judy Oppenheimer’s excellent 1988 biography, Private Demons: The Life of Shirley Jackson.

Writing a biography is like navigating a marriage—intimate, demanding, thrilling, surprising. Biographers of writers face a special problem. They have to write about a life, and they have to write about a body of work, and they have to decide how the two things are connected. Fiction is not crypto-autobiography; it transcends the details of the lives on which it may or may not be based. Franklin fearlessly wades right into this deep water, decoding Jackson’s stories to understand the events of her life and vice versa. This readable book tells a scary story of its own, a story about the price of talent and the dark side of love. Most important, it honors and understands the writing of one of the 20th century’s great American storytellers.