The other day at lunchtime, I happened upon a photo essay on the Guardian’s website celebrating the 90th anniversary of Decca Records. The album covers on display had presumably been chosen for their arresting artwork, emblematic, in each case, of a different era. David Bowie was represented, as were Tom Jones, Lulu, Cat Stevens, John Mayall & the Blues Breakers (with Eric Clapton), Marianne Faithfull, Caravan, Davey Graham … But, I wondered, where were all the classical records? Yes, there was an obligatory shot of Frederick Delius’s Sea Drift, an early Decca release, recorded on six sides in 1929—a recording of such poor sonic quality that the title was removed from the catalog a mere three months after its issue. But that was the extent of it. Where were the glories of the Decca Classics vault—records by Joan Sutherland and Ernest Ansermet, Kathleen Ferrier and Colin Davis, Adrian Boult and Benjamin Britten, Mischa Elman and Julius Katchen? What about one of the operatic albums produced by John Culshaw, whose recordings of Wagner’s Ring Cycle with Georg Solti and the Vienna Philharmonic were as revolutionary as they were artistically important?

Last night, I went to my shelves and spent a few hours pulling albums, listening to music, lazily poring over liner notes. And I confirmed what I’d earlier suspected: that some of the album covers from Decca’s classical division were every bit as compelling as their pop music cousins. Here, then, a few of my favorites:

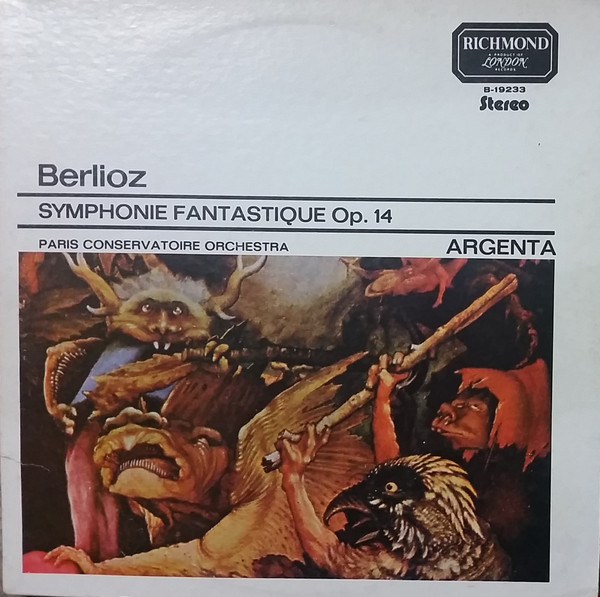

Hector Berlioz, Symphonie fantastique, the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, Ataúlfo Argenta conducting (1965)

This was my first exposure to Berlioz’s feverish Romantic masterpiece—my father played the record every Halloween when I was growing up, a tradition I have happily continued—and though the playing is a touch ragged (plenty of more polished accounts are available), this version remains my favorite. The ghoulish picture on the jacket gives the unsuspecting listener a taste of what’s to come: the harrowing Witches’ Sabbath in the symphony’s fifth movement.

Johannes Brahms, Piano Concerto No. 1, Clifford Curzon with the London Symphony Orchestra, George Szell conducting (1962)

I love Leon Fleisher’s fiery reading of this concerto with Szell leading the Cleveland Orchestra, but I am also fond of Curzon’s poetic approach. His reading is grand and exalted, and few pianists had a better sense of the architecture of this colossal work, the ability to shape each phrase so that it fits in logically with the whole. The jacket, too, is as classy as they come, with Curzon looking dapper and smart.

Richard Wagner, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, the Vienna Philharmonic, Georg Solti conducting (1976)

I had checked this massive set of records out of the library long before I owned it—for some reason, violin passages from the opera’s Act I prelude always seemed to turn up at youth- and college-orchestra auditions. At any rate, look at the dreamy medieval city rendered on the cover, and you’ll be in the perfect mood for what is a highly enjoyable performance of Wagner’s most joyous work. The singers (Norman Bailey as Hans Sachs, René Kollo as Walther, Hannelore Bode as Eva, and Bernd Weikl as Beckmesser) are top-notch, and the orchestral playing is full-blooded and tasteful.

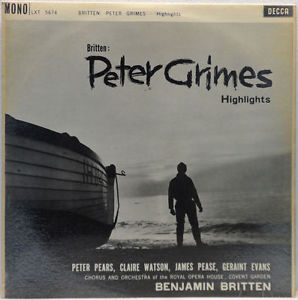

Benjamin Britten, Peter Grimes, London Symphony Orchestra, Britten conducting (1959)

The sense of foreboding conveyed by this black-and-white cover is a perfect match for Britten’s brooding, poetic work, with the tenor Peter Pears memorably singing the lead. Other Decca records advertised the company’s FFRR (full frequency range recording) technology—a high-fidelity technique made possible by the introduction of the LP in the late 1940s. This album takes advantage of the company’s next technological iteration: FFSS, that is, full frequency stereophonic sound. Even on my third-rate speakers, the sound is indeed robust and rich.

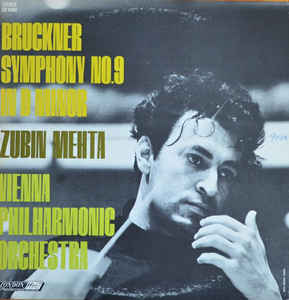

Anton Bruckner, Symphony No. 9, the Vienna Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta conducting (1965)

Mehta was only in his late 20s when he gave this sumptuous account of Bruckner’s final, unfinished symphony, by turns stately and blazing. The cover photograph certainly captures the matinee idol good looks of the young Mehta—he gazes out mid-phrase, baton in hand, pensively and philosophically—but like the late Romantic recordings he would later make with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, this one has as much substance as flash.

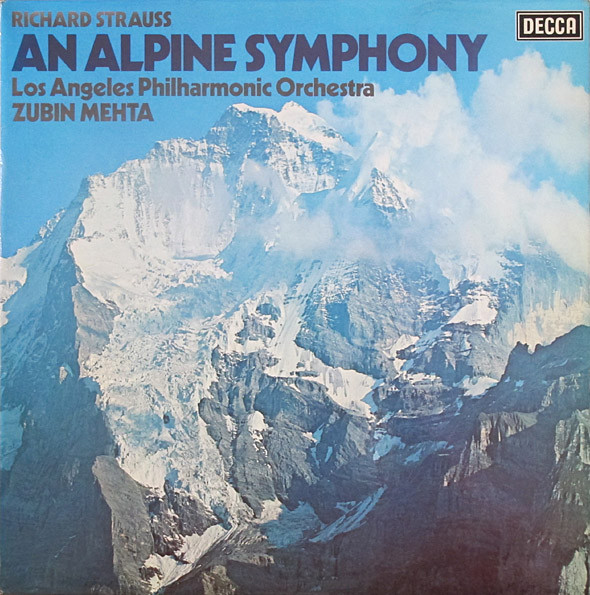

Richard Strauss, An Alpine Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta conducting (1976)

This is one of those Mehta-L.A. collaborations. Mehta has always been consistently undervalued and underrated, but his Austro-Germanic credentials are as solid as they come, and over the past five decades, his recordings of the late-19th-century repertoire hold up beautifully. He elicits, among other things, a lush, glorious sound from his Los Angeles musicians. And the mountain landscape on the album cover will have you dreaming of the heights.