Dianna Frid, who teaches at the University of Illinois–Chicago, has been working for several years on a multimedia project called “Text-Textiles,” pieces of which have been exhibited in various contexts since 2014. Here, Frid discusses why she works in textiles, why sewing is similar to writing, and what viewers can expect from her multimedia canvases.

“I went to Hampshire College to study anthropology, which was a way to defer the more difficult choice to become an artist. Art felt like something I had been exposed to my whole life in terms of material culture: crafts, textiles, and people making things around me. I left Hampshire to go to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to study sculpture. After I graduated, I traveled around and worked various jobs, but I intuitively knew that I wanted to teach. Right now, I’m teaching an intermediate drawing course for undergraduates, and they’re all working with textiles.

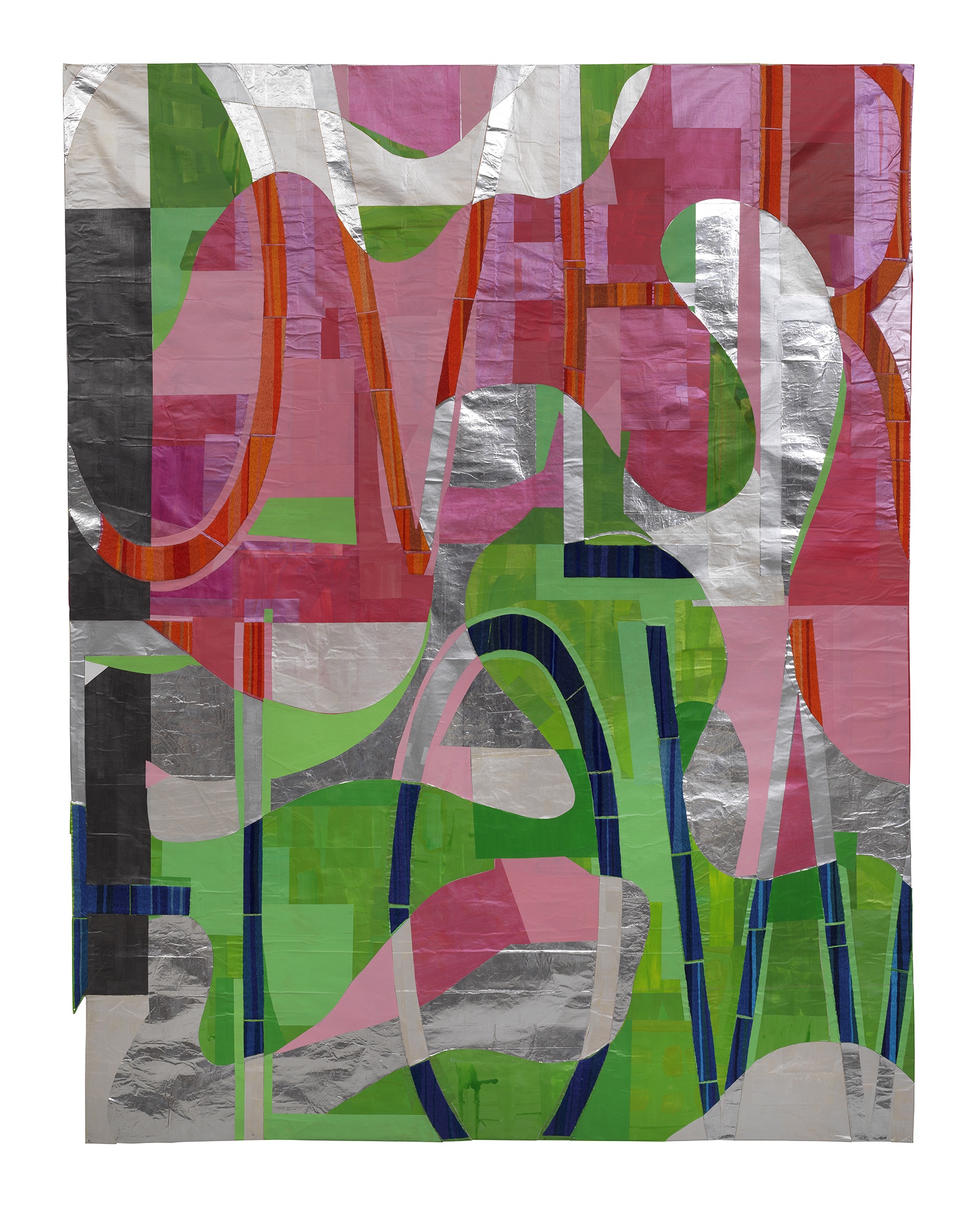

There’s embroidery but also graphite and aluminum in my work. Historically, women and people of color across the globe work the most with textiles. A lot of younger women across the global north learn how to write by making samplers with letters—that’s how they learn their letters. My way of working with cloth and textiles is mixed media. Sewing words is a way of building with language one stroke at a time. For me, there’s something concrete and factual about it—something mysterious in how we construct graphemes that begin to mean something. The relationship between text and textiles is the same as the relationship between writing and making cloth as code that can be deciphered and understood. Not everything is reducible to words. Words in works of art can be interpreted in a multitude of ways, and they’re limited in expressing ideas. What do you see first? Does the word communicate the signifier in the form of a word, or is there something greater in the nonverbal sense? When I exhibit these works, there’s not a lot of dialogue at the openings. People are there to celebrate and look at art, but I’d like to know what people have to say about these pieces.

I read a lot. I’m interested in how poets think of language as matter and material. One of my pieces from this series is called Rhythm Rhythm Rhythm. I had been reading a book by Vladimir Mayakovsky called How Are Verses Made? He kept talking about rhythm, and I thought, ‘That’s what I do when I sew—there’s a rhythm to it.’ The textile patterns are rhythmic in that piece, so it became a process of language, poetry, and sewing. I ended up making several pieces inspired by Mayakovsky and playing with this idea of repetition.”