Dmitri Wright has lived in Greenwich, Connecticut, for 30 years, and is the master artist at Weir Farm National Historic Site. While he has painted landscape scenes around the world, Wright keeps returning to the agrarian beauty of Weir Farm, which is dedicated to American Impressionism. Here, he discusses his approach to painting the ephemeral, the lineage of his artistic tradition, and why Weir Farm has captured his full attention.

“I was born and raised in Newark, New Jersey, and grew up in the projects. My path to becoming an artist started out in junior high school when an art teacher said to me, ‘Dmitri, you have talent, and you should consider becoming a fine artist.’ I said, ‘What’s that?’ As an inner city kid who didn’t have exposure to art, my ambition at the time was to become either a Marine or a cross-country truck driver. She encouraged me to take a test and apply to Arts High School. I took the test, got in, and was surprised to find other people like me. I started out in the high school and then moved upstairs to the college. I graduated first in my class.

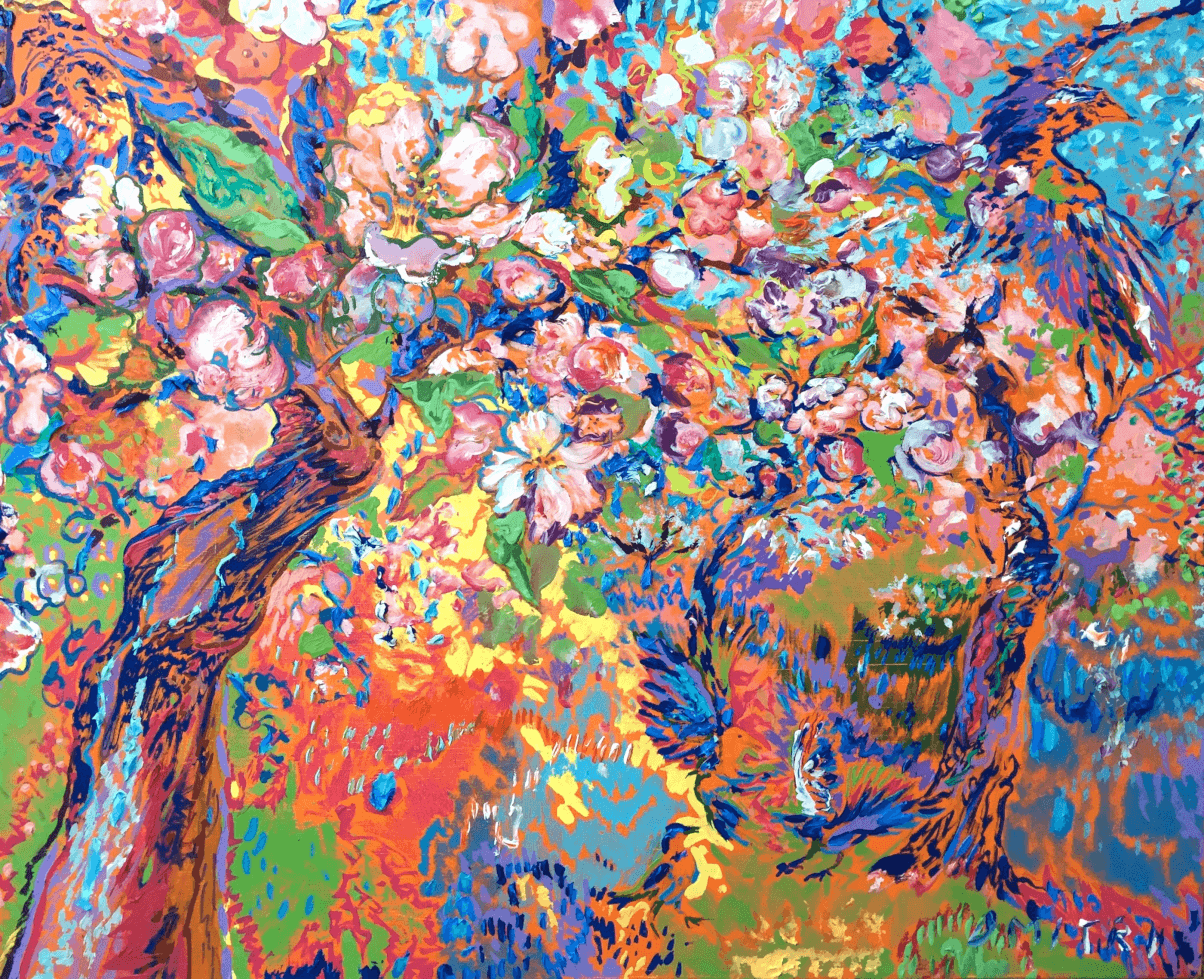

I believe my landscapes for the most part are about transcendence. When one has the opportunity to paint en plein air, it’s quite liberating in comparison to studio painting. The Impressionists opened up a wonderful door where the artist is allowed to paint from their sensations. Sound, smell, and taste—those things are utilized more than just the eyes. My latest work is a combination of the elements of the legacies of Impressionism, because they all have something to offer. With Neo-Impressionism, the experiential is important in terms of the sensations coming through the eye and the optical mixing of the colors. With Fauvism, it’s about the heart at the center of the works: What do I have to say about this experience? What am I feeling? From a Fauvist standpoint, a tree might be painted orange because that’s a more appropriate way of communicating an emotional sensation—using color as symbol rather than a representational illustration of a sense of place. With Deconstructionism, I break things apart and put them back together in a whole new way. I think beyond what’s there, to the core of the subject. And with the Surrealist element, I often paint consciously and unconsciously. I take each element of these legacies of Impressionism, and that’s why my paintings look the way they do.

Weir Farms is the only national park dedicated to painting. It makes me inspired to realize, ‘Wow, there’s a whole national park that’s dedicated to artists.’ There are some very beautiful things there. I’ve always liked American farmhouses and barns, just like American Impressionist Wolf Kahn. That’s one reason I started to paint there. You get out in nature and you feel its embrace, it’s quite profound. The European pastoral works that I do are different than the Weir Farm series. I try to do the European paintings in the French Impressionistic style, and the Weir Farm paintings in the American Impressionistic style. I work very hard to make a distinction between the two, but as time goes on, the two are morphing into one style. I think that happens naturally. All artists, scientists, and designers are looking for the elegant idea. We don’t want to get more complicated—we want to get simpler, we want to get right to the core of what you’re trying to say. That’s what the art form really is, that’s where the pulse is. You want to put your finger on that pulse. As time goes on, perhaps you’re not as physically strong as you used to be, and you know that you only have so much time left, so you want to get right to the heart of the matter. But as one falls in love with the elegant idea, you get to what you want to say.”