In 1887, when real estate developers Harvey and Daeida Wilcox founded the Hollywood subdivision outside Los Angeles, there were already two famous Hollywoods in America: a luxury hotel in New Jersey and a cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. The cemetery was especially well known, celebrated in newspapers nationwide as a kind of Confederate Valhalla for secessionist luminaries. So it’s surprising that if you search online for the origins of Hollywood’s name, neither of the two appears.

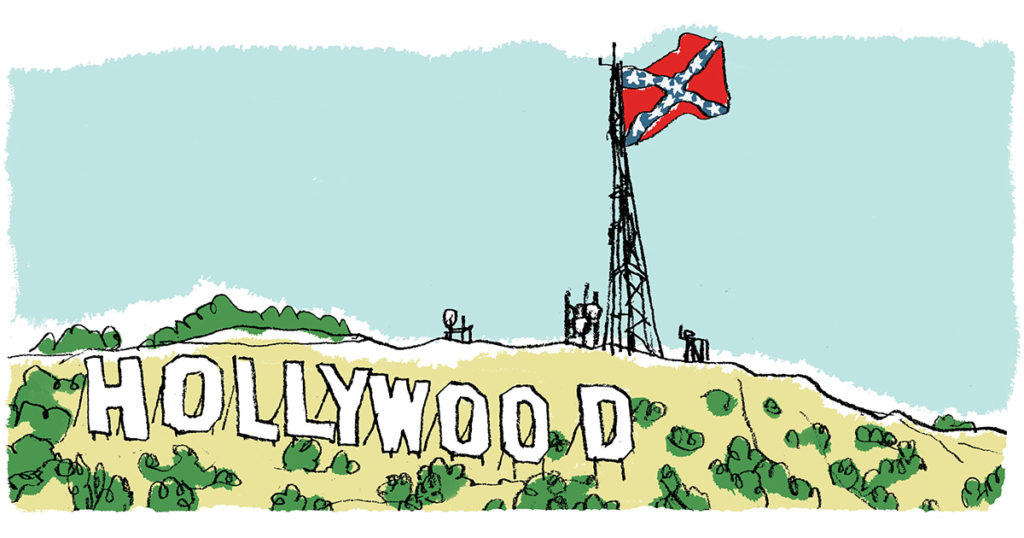

Why has there been a collective forgetting of the 19th-century history of “Hollywood”? Is it because both famous Hollywoods had intimate ties to the Old South, and Californians are attempting to prune Confederates from Hollywood’s family tree?

That’s getting harder to do, now that Kevin Waite has produced West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire (2021). Waite writes that in the mid-19th century, Southern California experienced an influx of settlers from slaveholding states who sought to extend slavery all the way to the Pacific. As a result, during the Civil War, Los Angeles was a hotbed of secessionists. “Let it never be forgotten,” declared the San Francisco Bulletin’s Southern California correspondent in 1862, “that the county of Los Angeles, in this day of peril to the Republic, is two to one for Dixie and Disunion.” Hundreds of these rebel sympathizers went east to fight for the Confederacy, and about 80 joined the Los Angeles Mounted Rifles, the only Confederate militia to be organized in a free state. Meanwhile a federal garrison was stationed in Los Angeles County, after General Edwin Vose Sumner, commander of the U.S. Department of the Pacific, complained that he was struggling to contain tens of thousands of pro-Confederate Californians. Even in the wake of the Confederacy’s defeat, L.A.’s secessionists continued to push a white-supremacist agenda: California was the only former free state, during Reconstruction, to reject both the 14th and 15th amendments, which granted citizenship to former slaves and gave Black men the vote.

After reading Waite’s book, I began to understand why Southern California responded so enthusiastically, in 1915, to D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, and why the film industry so readily embraced Margaret Mitchell’s Lost Cause epic, Gone With the Wind. As James Baldwin later wrote, “There is not one step, morally or actually, between Birmingham and Los Angeles.” Yet for all of his excellent research, Waite does not address the Confederate history of “Hollywood”—an important story if we hope to understand the nationwide legacy of the Lost Cause.

Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery was established in 1847 by a pair of wealthy Virginians who had visited Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and wanted to build an equally grand garden cemetery for the South. They got the name from the property’s holly bushes, which flourished in southeastern soil and had inspired a host of smaller Hollywoods, including a Hollywood resort in Mobile, Alabama, a Hollywood vineyard in Natchez, Mississippi, and Hollywood Plantation in Benoit, Mississippi.

In 1858, Hollywood became firmly established in the national imagination when President James Monroe’s body was disinterred from a New York City grave and transported to Virginia. Details of the commemorations surrounding the president’s reburial, which attracted thousands of southerners and lasted several days, were publicized in The New York Times and other newspapers across the country.

Hollywood continued to make news during the Civil War whenever a favorite son of the South was buried. Most notable was the funeral of President John Tyler in 1862. Although Tyler had requested a simple burial, Jefferson Davis devised an elaborate political event to celebrate the southern cause. Two years later came the burial of J. E. B. Stuart—the much-idolized young cavalry commander—and Hollywood was on its way to becoming the holy wood for Confederate heroes.

In May 1866, just over a year after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, a vast crowd of Richmonders gathered to place flowers on the cemetery’s Confederate graves, which numbered in the thousands. The Richmond Times, in an article reprinted in newspapers as far afield as the Dallas Herald and New Orleans Times, described the event as “the pilgrimage to Hollywood, the Mecca of the South.” Attending the following year’s “pilgrimage,” the Richmond correspondent of The New York Times wrote, “There is not this morning, we suppose, a single flower left upon its stalk in Richmond or its environs,” since “troops of little girls” gathering flowers had completely “traversed the city.”

Meanwhile, southern women went about transforming the cemetery into the official city of the Confederate dead. The Lee-Custis family estate, Arlington, had been appropriated by the federal government in 1861 and was later made into a national veterans’ cemetery, but Confederates were banned from that ground. The Ladies Hollywood Memorial Association embraced the mission of bringing to Hollywood the remains of Confederates that were, at that point, scattered across the country. In 1869, they erected a 90-foot granite “Confederate Pyramid” at Hollywood, which today is surrounded by the graves of 18,000 Confederate enlisted men, including most of the almost 3,400 soldiers who, by 1873, had been disinterred from Gettysburg. Hollywood eventually became the final resting place of 28 Confederate generals, as well as Jefferson Davis.

By the mid-1880s, Hollywood Cemetery’s fame had spread to California. The Los Angeles Times first mentioned “Hollywood” on May 21, 1885, almost two years before the Wilcoxes founded their subdivision, in a brief item about the new Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Richmond. The name would also have been familiar to the Confederate veterans who dominated local politics. When the Wilcoxes arrived in California in 1883, the mayor of Los Angeles, Cameron Thom, was a Confederate veteran from Virginia who had fought at Gettysburg. None of this necessarily means that Daeida Wilcox or H. J. Whitley—a real estate developer known as the “Father of Hollywood”—borrowed “Hollywood” from Richmond’s cemetery (Daeida reportedly said she liked the word because holly brings luck). But it demonstrates that the word was an established part of American culture long before Daeida and other Californians adopted it.

Another famous Hollywood that preceded California’s was John Hoey’s Hollywood Hotel, in Long Branch, New Jersey—one of the most extravagant properties of the Gilded Age. In the 1880s, wealthy New Yorkers spent their summers reveling in Hoey’s extravagant gardens, and their winters marveling at his “miles of greenhouses,” described by The New York Times as a tropical paradise. According to one Times correspondent, “travelers from all parts of the country went to Long Branch to see Hollywood.” H. J. Whitley and Daeida Wilcox, therefore, might have associated the word with Gilded Age excess rather than unpleasant ties to the Old South. But if so, this would merely introduce one degree of separation: Hoey had made his fortune with money he earned in the Old South, when he extended the operations of the Adams Express Company south of Washington, D.C., to establish what became known as “Hoey’s Charleston Express.”

Hoey’s extensive southern business ties probably wouldn’t have troubled the New Yorkers who frequented his hotel. Like the early leaders of Los Angeles, members of New York’s elite were quite comfortable with southern culture. Many of them had prospered as loyal subjects of King Cotton. On the cusp of the Civil War, the city’s mayor, Fernando Wood, actually pushed for New York to secede from the Union and establish itself as a sovereign city-state so that it could maintain its lucrative business with slaveholders. The idea didn’t get far.

The New Yorkers at John Hoey’s hotel almost certainly would have known that it shared its name with Virginia’s cemetery. Before the war, New Yorkers visiting Long Branch had mingled with southern aristocrats, including Jefferson Davis, whose wife, Varina, was the granddaughter of New Jersey’s governor. After her husband’s death, Varina settled in Manhattan but was ultimately buried at Hollywood, along with her husband and children. When she died, her coffin processed through Manhattan before journeying to the much-romanticized cemetery. According to a piece published in The New York Times almost 40 years earlier:

Thousands visited the beautiful graveyard, wandered through its valleys and over its hills, and lunched on sandwiches and strawberries by the side of its cooling brooks. … Love-making, too, during the entire day was carried on to an unlimited extent, and many a troth was plighted, and many a doubting, fearing heart made glad, beneath the trysting shades and amid the grand mausoleums of romantic Hollywood.

It is difficult to imagine that the founders of Los Angeles’s Hollywood Cemetery, which opened in 1899, could have been unaware of its resonance with Confederate mythology. The Long Beach chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy made the connection explicit in 1925, when it put in place a six-foot granite monument to the Confederate dead, which was surrounded by 37 graves of Confederate veterans, including several who had been residents of the Confederate rest home “Dixie Manor,” in nearby San Gabriel. Yet today, the cemetery—now called Hollywood Forever Cemetery and home to a who’s-who of dead celebrities—doesn’t outwardly acknowledge any southern roots.

Neither did Hollywood’s Chamber of Commerce, when in 1989 it filed a trademark claim seeking royalties from other Hollywoods throughout America. One of them—Hollywood, Alabama (named in 1887, incorporated in 1897)—responded by painting “we’re the real hollywood” on its water tower. Ultimately, a judge balked at the idea that trademarks could be applied to names of incorporated cities and towns. However, the chamber of commerce did manage to trademark the all-caps Hollywood sign that presides over the Hollywood Hills, even though it looks suspiciously like the similar all-caps sign that already stood outside New Jersey’s Hollywood Hotel in the early 20th century.

All of this brings us back to Kevin Waite’s research for West of Slavery, which he outlined in a 2017 Los Angeles Times op-ed. There, he drew attention to the Confederate monument in Hollywood Forever Cemetery and explained why he hoped it would not be taken down:

It serves as a needed corrective to a self-congratulatory strain in the stories Californians tell about themselves. Angelenos might be tempted to view the current controversy over Confederate symbols, and the ugly racial politics they represent, as a distinctly Southern problem. But a visit to Hollywood’s cemetery plot and some historical perspective teach us otherwise.

Waite’s op-ed was published on August 4, 2017, just eight days before the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Four days after that national trauma, the monument at Hollywood Forever was taken down, and in 2020, after George Floyd’s murder, almost all of California’s remaining Confederate monuments were removed. Perhaps the monument at Hollywood Forever needed to go, but the inscription on its granite marker contained a valuable message that still bears thought: Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet, Lest we forget—lest we forget.