In a 2006 essay about a slate of autobiographical books dealing with pain and abuse—which anticipated the cultural winds that would grow into a storm with the help of social media—the novelist Benjamin Kunkel wrote: “Suffering produces meaning. Life is what happens to you, not what you do. Victim and hero are one.”

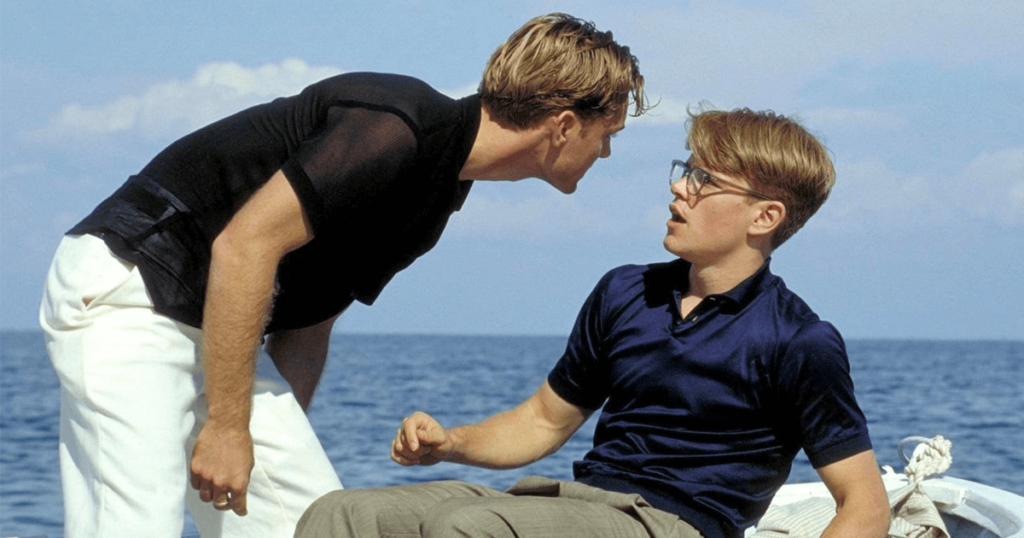

A confluence of two extraordinary recent stories drove this point home for me. On the one hand, there was the stranger-than-fiction New Yorker profile of the best-selling thriller writer Dan Mallory, who willed himself to be a real-life Talented Mr. Ripley (thankfully, without killing anyone), spinning wild tales about his family life and inventing ostentatious, life-threatening illnesses to gain sympathy and professional advantage. On the other was Jussie Smollet’s alleged hate-crime hoax, in which the actor appeared to have staged his own assault in order to garner the nation’s sympathy and attention.

The one is an instance of the kind of entrepreneurial suffering that Kunkel was observing in his essay. James Frey and J. T. Leroy, to name just two of the most indulgent cases, also profited from tall tales of personal misery, but the difference is that they put that material into their writing, whereas Mallory turned his entire life into a work of fiction. The other is an example of the worst kind of social-justice hypochondria that increasingly undermines progressive debate. Both cases are sadly exemplary of the un-heroic era we find ourselves in, an era in which the greatest social currency increasingly accrues to those who present as the most set-upon victims—regardless of their actual circumstances.

Perhaps this is only to be expected. “In a society less egalitarian by the day,” writes Kunkel, “we pretend to a curious democracy of trauma.”