A few years ago, my nephew, Luke, began college at Emory University. Because he was far from home, I wrote him letters. At my kitchen table in northern Utah, I imagined Luke sitting on his bed in his Atlanta dorm room, a room that for me looked exactly like the one I inhabited as a freshman when I moved 2,000 miles away from home and first started writing letters of my own. In each letter to Luke, I wrote about my day, my students, and the latest antics of my sons. Then I sealed the envelope, found a stamp, and sent it off.

Only Luke never received the letters. Weeks into the semester, I texted him to ask if my letters had arrived. They hadn’t. The letters were lost; I was devastated.

“Just print them again,” my friend said when I told her what happened.

But I couldn’t. I had written each one by hand, blue ink on cream paper. And even though I had been studying letters for years and had written a book about the letters of Georgia O’Keeffe, I was stunned by the loss. It wasn’t the content I mourned; it was the fact that Luke had not known he had been held in my hand.

O’Keeffe had better luck. Of the more than 25,000 pages that she and her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, exchanged during their 30-year correspondence, not a single letter appears to have been lost, redacted, or misplaced. They fell in love through letters—long, beautiful, glorious letters that they first exchanged between 1915 and 1918, years in which he lived in New York and she spent most of her time in West Texas. To read those letters is to read two souls aflame. “How I understand every pulse beat of yours,” Stieglitz writes to her. “All of me seeming to cry out to you,” she responds, “—for you—to give to you and take from you—to give all that I have to give to you.” Her letters match “the fifty mile gale” outside his house as he reads. “Here I’m again with you,” he writes, “another wonderful living bit of flesh & blood of yours in the shape of a letter.” When she receives his: “I wanted to kiss it—it seemed made for lips.”

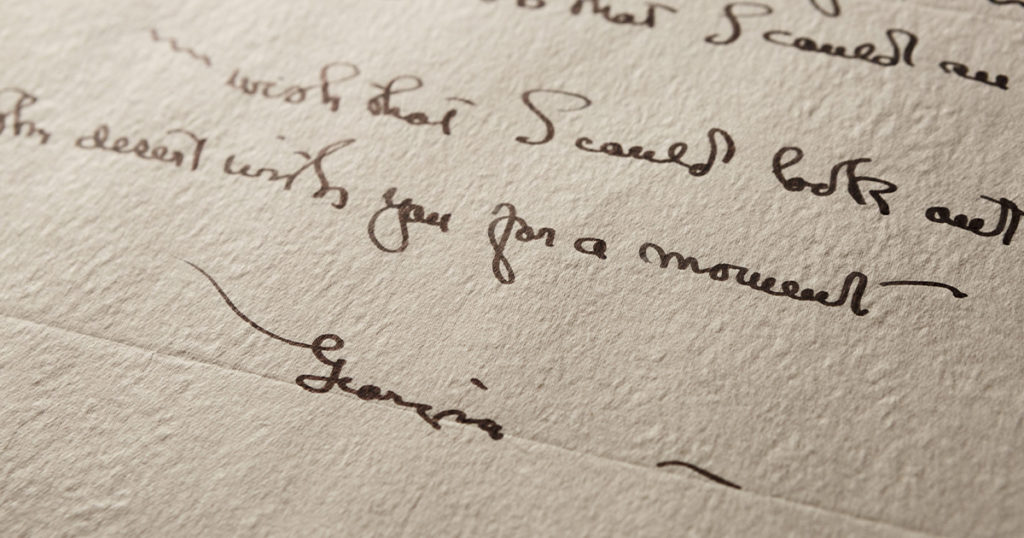

Letter after letter, sometimes several in a day. And not just during their early years but throughout their lives together, bequeathing us one of the most complete and vibrant correspondences ever created. Even when phone calls became possible, they wrote. Even when they lived a few blocks away from each other in New York, they wrote, recognizing that physical intimacy didn’t simply replace the intimacy of their letters. Transcendent letters with hardly a word crossed out, hardly a blemish on the page, as if their thoughts arrived whole and perfect and already formed.

Whole, that is, except for the gaps. The blank spaces. The long wave-like dashes that can travel the length of a line, or a page. In O’Keeffe’s letters, we find almost as much emptiness as fullness and learn to value those spaces even more than the words. As a modernist, O’Keeffe sought the void in her visual art: her pelvic bones, her fishhooks, her never-ending skies. You see that same aesthetic shaping her letters—not just margins but holes, canyons, rifts. So much exists in the empty places of her letters, sometimes unbearable pain or sadness. More often, the gaps reveal her own inability to find the words to express the vastness, the immensity, the brilliance she found all around her. Time and again, in reference to both painting and writing, she asks: “I wonder if I got over to anyone what I want to say.” In fact, her entire life’s work can be described as an effort to translate her experience of being in this world. And it is those voids in both her visual and her literary art that ultimately draw us in so deeply—for it is into those gaps that we fit ourselves.

I have been writing letters my entire life. The first ones traveled from my dorm room in Nebraska across the Pacific to reach my parents in Hawaii at a cost of 22 cents. Years later, I wrote to a boyfriend, begging him not to leave me. I wrote to my husband the year we lived apart. I wrote to my aunt to apologize for telling her story in my memoir. Before she died, I wrote to my mother-in-law every week, long after she could not write back. And for years now, I have sat down every Sunday at the kitchen table to write to my father. He has trouble hearing, and phone calls leave him frustrated and left out, but a letter allows for quiet communion between writer and reader. When I write to him, I hold him in both head and heart as I move the pen across the page. It is nothing short of prayer. The letters I write my father are easy and open. I rarely address hardship or sadness, especially in this past year. But I have received enough difficult letters in my life—from family, friends, or lovers who rage or accuse—to know that even those letters are really love letters. You take the time to write only when you care, even if what you inscribe are your wounds.

A handwritten letter is singular, never to be repeated, floating almost unrecognizable amid the sea of instant communication and Twitter-sized thoughts. A letter is neither immediate nor efficient, values we have come to assume as the only possible measure of communication. A letter requires patience, time. You send your letter to the intended, and then rest in the gap as the letter—your very thoughts embodied on the page—makes its way across space to arrive at the moment it is unfolded and held again. Just like an O’Keeffe landscape, letters bring together the near and the far away, binding reader and writer over space and time, tethering us to one another. They materially attest to a body, a relationship, and a particular moment. I end with O’Keeffe at the mailbox:

And I dropped the envelope for you into the letter box—And as I knew it was no longer in my control, it struck me what a wondrous thing a letter box is—What its powers are.—I have no idea what went away in that letter—Except that it was myself—As always.—To you—To everyone.—