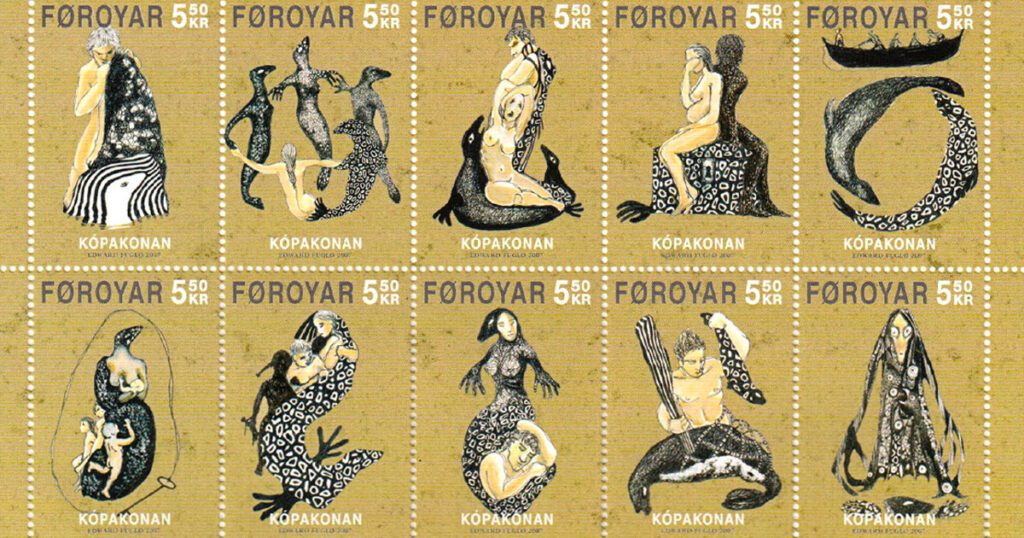

Someone with annoying, persistent behavior, someone who goes on and on, is tiresome. A friend, for example, who won’t shut up about some silly exploit. Or a child whining for something, a sweet, a story, or just the answer to the question “How long till we get there?” Or a suitor who won’t take no for an answer. In Spanish, the word for a tiresome person is pesado, which also means heavy, suggestive of how someone who is insistent can wear you down, first a pressure and then a weight, until you collapse and give in. I expect that such a suitor was the silkie in the song of that name, “Silkie.” A silkie is a mythical creature, man on land and seal in the water, and the ballad, originating in folklore from the Orkney Islands, has many versions. The one I know is Joan Baez’s, where the silkie is a grumbly guest. But in another, he was grumlie, Scots for gloomy, when he came to the bedside of the woman in the story. Nine months or more later, in the opening stanza of the song, the woman sits and sings to her baby, lamenting how little she knows of her baby’s father or the land where he dwells.

I found no definitive version of the song, and depending on which one of the many you consult, you get a different mix of verb tenses and thus a slightly different notion of what really happens. Does the silkie only say he’ll return for his child, or does he actually do so? Does he give the woman a bag of gold as her nurse’s fee, or merely promise to? Does he appear at the foot of her bed or reappear there? Amid the confusion from verb tenses that do not link into an easy chronology, one element of the song is clear: the passivity of the woman. All she does is sit, singing to her baby and wondering about the father. Everything else is the silkie’s doings, from his first visit to his promise to return for his child to the prediction that the woman will marry a gunner, who, with his very first shot, will kill both the silkie and his young son.

When the woman hears that terrible prophesy, why doesn’t she jump up and do something? She doesn’t react at all on hearing it and apparently makes no plans to prevent the silkie from coming for his son, though she’s been armed by him with knowledge of the day it will happen: When the sun shines bright on every stane. Why so passive? Maybe she is in shock at the enormity of her loss as just foretold: her baby to be taken from her, and, a little down the line, the boy’s life ended by her own fine new husband. Why doesn’t she do something on hearing that dreadful doom?

And for that matter, why didn’t she turn the silkie away when he had first appeared at her bed, cheekily announcing that he was the father of her baby when she didn’t even have a baby yet?

Certain fates are unavoidable. They play out so often that they have worn a deep groove. The way is made, and life, like a cart bearing us along, settles into those tracks. It doesn’t matter that it is all new ground for us; others have come before, the way is made. The ground itself has a history. A stranger appears beside your bed as if in a dream, and you dreamily make room for him. Especially if he announces that he is the father of your baby. Is. A different verb, as for example in “I will be your baby’s father,” might be countered. Will, as I taught my pre-intermediate class of young teens this past spring, is for either an offer, which can be refused, “Thank you, no,” or for a decision, which can be combated with a contrary decision, “You will not!” When will is used for a prediction, then all you have to do is cross your arms and say “We’ll just see about that.” Had the silkie chosen be going to, used for a plan, and said, “I’m going to be your baby’s father,” the woman could have quashed the plan with a withering look and a counterplan: “I’m going to have no baby.” This verb tense is also used for events that are unfolding, that you can see practically see happening, as when someone stands near the edge of a cliff and you immediately visualize the fall. But the silkie made his announcement before things had got underway.

In English it is also common to use the present tense for scheduled events, as if they were set in stone. “I catch the train at 8:15,” or “I start work on the 12th.” The present tense makes these happenings, no matter how mundane, seem inescapable. It is not yet but it might as well be. “Eat and be merry, for tomorrow we die.”

One day this past spring, in my class of pre-intermediate teens, while on the verbs for the future, we stopped mid-exercise to watch a couple of workmen on the roof of the building just across the street, where they were replacing some tiles. We strained to see if they wore safety harnesses. They moved confidently across the roof, not crouching and grasping with every finger for a hold but standing upright. “Good heavens,” I said, watching them. “Do you think they’ll fall?” That was asking for a prediction, though I didn’t really want one. You don’t bet on someone’s life. The workmen appeared at ease, almost gay. “Don’t worry, we won’t fall!” one might have called out, seeing us gawking.

One of those workers, however, might very well have rolled his eyes at how tiresome people can be with their fears. The view is fine from the roof, the breeze is cooling. Why must someone distract him with worries? That steep pitch, that child wailing in your arms, that dire prediction that keeps you from attending to the sun, to the flowers, to the breeze. Shaking their heads, the workmen might just as well have called out, “Let us laugh and be merry, for tomorrow we fall!” And so we do. Into the cart that bears us along. Maybe the woman didn’t react to the silkie’s prediction because there was nothing to do. Perhaps she was doing the only thing that she could, in transit as she was in the cart—envisioning the sun he spoke of, the brightness, the mesmerizing glint on every stone.