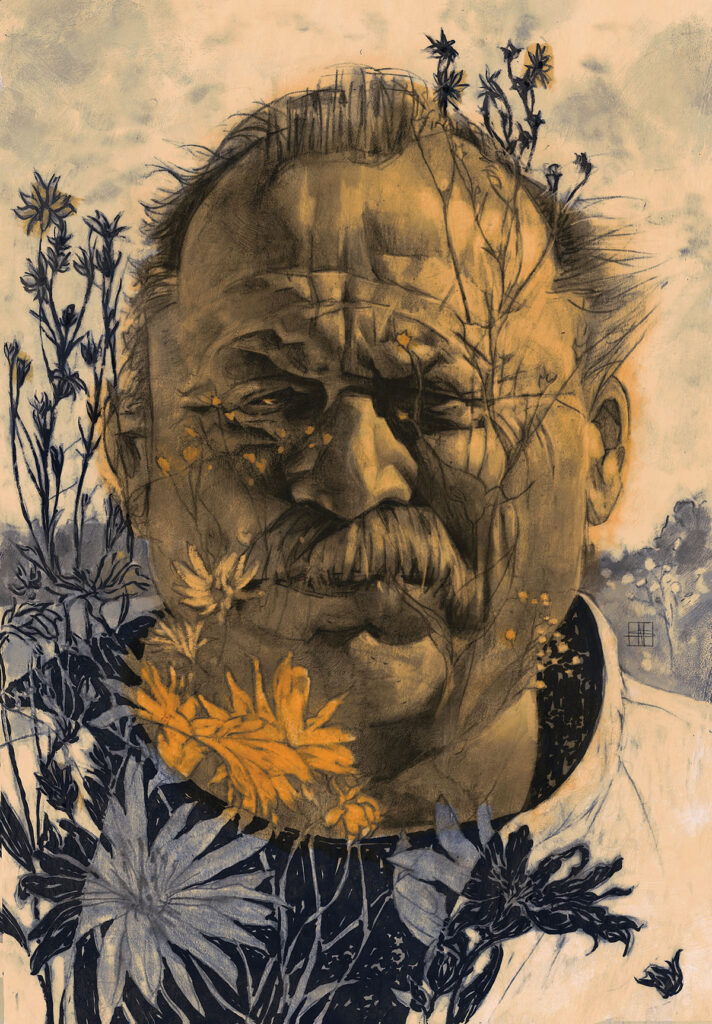

He fell off the cliff of a seven-inch zafu.

He couldn’t get up because of his surgery.

He believes in the Resurrection mostly

because he was never taught how not to.

—“Where Is Jim Harrison?” Dead Man’s Float, 2016

Growing up in rural Vermont and later in the Finger Lakes region of New York State, I was a bookish youth, reading and making attempts at writing from an early age. Both of my parents were readers, there were several good-size bookshelves in the house, and early on I was provided with a desk and a bookshelf for my room. Most every birthday and Christmas, there would be at least one book among the gifts. I was read to, as well, an event that was not limited to bedtime. I vividly recall my mother reading Howard Pyle’s The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood aloud to me on the lawn, in the shade of a maple tree.

Our rural public libraries, in both Vermont and New York, were small but well stocked and well regarded. They were essential to my development—no home holds enough books to satisfy the cravings of a literary child. Many small-town libraries, including the one in New York, were built with grants from Andrew Carnegie, earning this robber baron a shot at a separate level of notability. Good often comes from bad, and balance between the two is always a floating question, never quite to be answered. Carnegie’s stated intention was simple and essential to a healthy democracy: to make knowledge and information widely available to any who sought it out. What people made of that information was up to them.

By the fourth grade, I began to pay attention to those shelves devoted to a rotating array of new works of both fiction and nonfiction—books not added to the permanent collection but available for a time to the patrons. My first significant discovery was Charles Portis’s True Grit, a book that writers often claim to be their favorite “unknown” novel. In any event, I read it even before the first movie (starring Kim Darby, John Wayne, and Glen Campbell) was made from it in 1969. In fifth grade, I wrote a book report about the novel, earning a note that my teacher made on the page—that there was no such things as “shoats,” which I’d mentioned for reasons lost to time. Her comment was wrong, reinforcing what I already understood about authority.

A few years later, when I was a young teenager in late-Nixon America, that same revolving bookshelf began to fill me with all sorts of new materials and ideas in the form of Richard Brautigan’s The Hawkline Monster, Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers, and Jim Harrison’s A Good Day to Die. There were others, but these three I read over and over again. They were new and fresh and spoke to me in ways that Hemingway, Steinbeck, Conrad Richter, and others could not. Of course, some of those works I truly wasn’t ready for, but my understanding of the Harrison and Stone novels would grow over time.

Now, recalling finding A Good Day to Die all those years ago, I wonder why, in our hours of conversation and pages of correspondence, I never told Jim that story, knowing as I do that it’s the sort of story writers love to hear. Jim grew up in northern Michigan, and both of his parents were readers, so it’s reasonable to guess that public libraries were an important source of books, of stories and voice, for that young writer as well. Still, it was never a topic we broached, and so, thinking about it, I couldn’t speak with certainty that he did partake of libraries. But then one day, I rose from my desk and walked to the bookshelves and took down my copy of his novel Sundog. It so happens that this was the first newly published book of Jim’s that landed in my hands, and I read it several times over while waiting for another one, the tattered cover and stained pages being testament to my love of that tale. As I remembered, the central character—a native of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and, as is often the case, a man who shared many of Jim’s passions and delights—was largely self-educated but a lifelong reader. Who had cartons of books shipped to him at remote job sites around the world. Who mentioned as a boy stopping by the small county library to see if anything new was on the shelves. And so, there it is. Writers reveal themselves in their works, if you only know how to look.

Jim wrote entirely in longhand, and he loved his fax machine. Many mornings, I’d wake to find a late-night missive in my machine, most often a new poem. Letters passed back and forth—our last exchange was less than a month before his death in March 2016.

Jim was a poet before he was a novelist—his first published book was Plain Song, a collection of verse that appeared in 1965. In a sense, he was always a poet who wrote everything else to support the practice of poetry. The story goes that when Jim was recovering from a bad fall suffered while bird hunting, Thomas McGuane suggested he try his hand at a novel. I suspect the idea had been there all along as he struggled to support his family from poetry, up in northern Michigan, in rural Leelanau County. McGuane’s prodding resulted in Wolf: A False Memoir (1971). He’d already published several books of poetry and three novels (including A Good Day to Die), none of which made a great splash, when he found himself broke, and not for the first time. With the help of a considerate financial gift from Jack Nicholson (to whom he had been introduced by McGuane), Jim holed up in a hotel and wrote the three novellas that made up Legends of the Fall, a breakthrough book for him. Part of this success was due to Jim’s coming into the realm of the first of the three great publishers of his life—Seymour “Sam” Lawrence, who over the years maintained his own imprint even as he moved from Dell/Delacorte to Dutton to Houghton Mifflin. In the early 1980s, Sam began a practice that has since become almost an industry standard: he kept his authors’ books in print, in handsome paperback editions, even as he published their new works in hardcover.

Login to view the full article

Need to register?

Already a subscriber through The American Scholar?

Are you a Phi Beta Kappa sustaining member?

Register here

Want to subscribe?

Print subscribers get access to our entire website Subscribe here

You can also just subscribe to our website for $9.99. Subscribe here

true