A hundred years ago, Claude Debussy lay dying, confined to his Paris bedroom, the symptoms of his rectal cancer becoming more and more intolerable; only his beloved cigarettes, and regular doses of morphine, provided any relief at all. Over the previous few years, a period that saw Debussy depressed and mired in debt, his composing had been increasingly labored and sporadic. He had intended to write a set of six instrumental sonatas but managed to complete only two, having struggled in particular with the finale of his Sonata for Violin and Piano. The war had added to Debussy’s misery, and during the final few days of his life, a new German offensive on Paris commenced, with the terrifying, long-range howitzer known as Big Bertha firing massive shells—more than 300 of them—into the city, from a distance of 75 miles away. Some 250 Parisians died. More than 600 suffered injuries.

On the morning of March 21, 1918, Debussy’s friend and biographer Louis Laloy paid the composer a visit. Laloy announced that a dress rehearsal was taking place that afternoon, at the Opéra de Paris, for a performance of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s lyric tragedy Castor et Pollux. (The rehearsal, originally scheduled for the evening, had to be moved up, on account of the anticipated air-raid sirens after dark.) “It was one of [Debussy’s] last regrets,” Laloy recalled, “not to be able to go to it. Seeing I was leaving, he tried to smile and whispered: ‘Say bonjour to Monsieur Castor!’”

Rameau composed Castor et Pollux, his third opera, in 1737 and substantially revised it in 1754. (Both versions exist today, and opinion is divided on which is superior.) It tells the story of the famed brothers, one mortal the other immortal, both in love with the princess Télaïre, who in turn has eyes only for Castor. When Castor is slain, Pollux, driven by despair, descends into the Underworld with the intention of trading places with him. Knowing that his own love will remain unrequited, Pollux decides to sacrifice his life among the living for the sake of his brother. Yet a terrible chain of events follows, and a hopeless situation is resolved only by the grace of a deus ex machina.

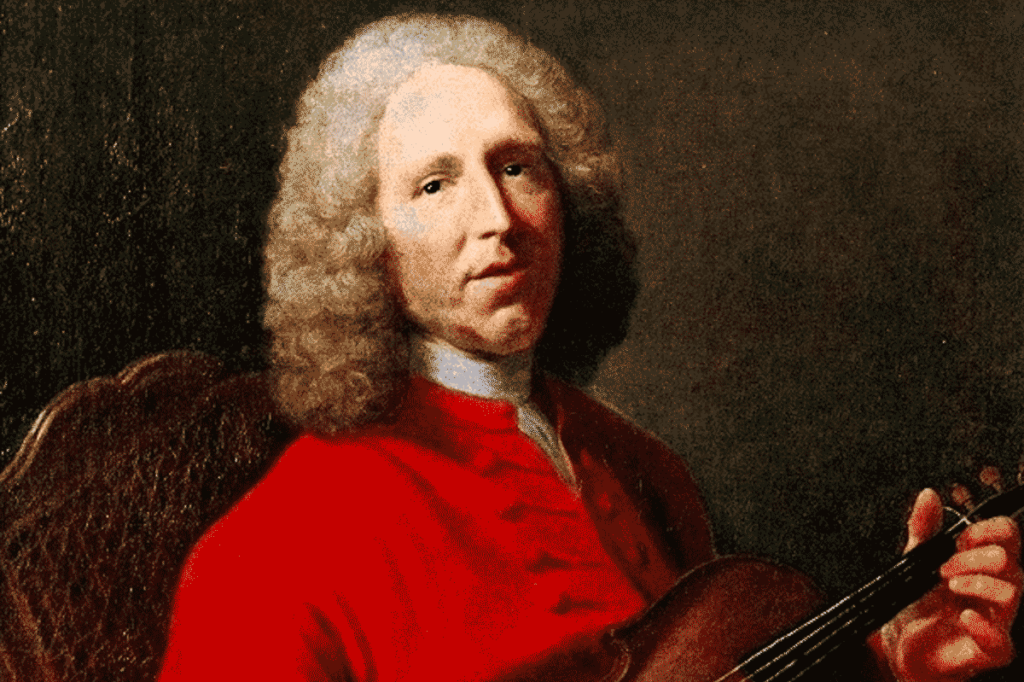

The opera contains some of Rameau’s loveliest music—Télaïre’s moving first-act aria Tristes apprêts and Castor’s heartfelt Séjours de l’éternelle paix, sung in the fourth act, amid the Elysian Fields of the Underworld. Yet it’s hard to imagine, when we listen to the work today, just how controversial this score was in the 1730s, a time when Rameau was challenging the established Jean-Baptiste Lully for supremacy on the French operatic stage. Rameau was no young Turk. The author of a famous treatise on harmony published in 1722, he didn’t write his first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie, until the age of 50. Lully and others with conservative musical tastes attacked what they perceived to be brazen, controversial, and heretical in this work: the adventurous harmonic language, the complicated vocal lines, the hyper-expressiveness. So intense was the divide between the conservatives and the liberals, and thus between Lully and Rameau, that the two camps took on names: the Lullistes and the Ramistes. Rameau prevailed, but, as so often happens, he himself was later viewed as outdated and conservative, when a more demonstrative, Italianate style came into fashion.

Not until the early 20th century did a Rameau revival take place. In 1903, the composer Vincent d’Indy put on two acts of Castor et Pollux at the Schola Cantorum conservatory in Paris’s Latin Quarter. Debussy was in attendance that day, and his review in the newspaper Gil Blas was effusive in its praise:

One is forced to admit that French music has, for too long, followed paths that definitely lead away from this clarity of expression, this conciseness and precision of form, both of which are the very qualities peculiar to the French genius. I’ve heard too much about free exchange in art, and all the marvelous effects it’s had! It is no excuse for having forgotten the traditions founded in Rameau’s work, unique in being so full of wonderful discoveries.

Every chance he got, Debussy now extolled Rameau’s virtues, not only that sense of clarity he believed to be essential to French art, but also the music’s “elegance and simple and natural declamation; above all, French music wants to please—Couperin and Rameau are the ones who are truly French.” Of Rameau’s many operas, Castor was Debussy’s favorite, and when I picture him bedridden, with the First World War approaching its denouement, I can imagine that his desire to hear the work one last time would have had a patriotic dimension, too.

When the war began, Debussy took to signing his letters, musicien français or Claude de France. The knowledge of some new outrage perpetrated upon France only heightened his nationalistic spirit. Had he not been so ill, he would most certainly have fought, having previously expressed his readiness to die for the cause. He spent his energies advocating on behalf of French music, demanding that it return to a purer course. The artistic precepts outlined by Rameau provided an antidote to Richard Wagner and Christoph Willibald Gluck (composer of the operas Orfeo ed Euridice and Iphigénie en Tauride), whose Germanic sensibilities, Debussy believed, had been disastrous for the development of his country’s music. “French art needs to take revenge quite as seriously as the French army does!” he wrote to a former pupil in the autumn of 1914. The massive siege of March 1918 would have intensified Debussy’s zealotry. Yet instead of listening to Rameau, he heard instead the most awful German music he could imagine—Big Bertha’s shells detonating in the near distance. These were the sounds that accompanied his passing, on March 25, 1918.

Listen to tenor Christophe Einhorn sing the aria Séjours de l’éternelle paix from Rameau’s Castor et Pollux, here in the 1754 version, with Jean-Christophe Frisch leading the Ensemble XVIII-21 Musique des Lumière: