I saw Barry Jenkins’s film Moonlight for the second time last night, in Brooklyn, with a college buddy, his wife, and my sister-in-law. It is the coming-of-age story of a young man named Chiron, told in three acts, as he struggles to find love and his voice—and to come to terms with his budding homosexuality—in the face of poverty, harassment, and extreme parental neglect. I already wrote about the film and spoke with Jenkins here, but the subject merits a few more thoughts.

At the Nighthawk theater in Williamsburg—a kind of cinematic hipster fantasy where grilled fish tacos and buffalo cauliflower florets can be delivered to your seat mid-séance—the audience was almost completely white. My sister-in-law, who is from Moscow and still being initiated into American skin dynamics, remarked to me more than once that the film is almost completely black—not only are there no white characters, even in the background there are virtually no white faces. It’s not the first time she’d seen an all-black cast—she mentioned the television show Empire—but it was, perhaps, the first time two-dimensional stereotypes had been transcended to such a degree that she’d lost sight of that detail.

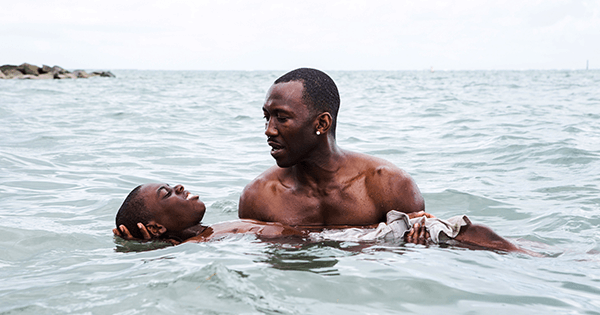

“No place in the world you can go ain’t no black people,” the drug dealer Juan tells a young Chiron after teaching the boy to swim. “We were the first on this planet.” The line is both shrewd and brilliant—with the de-marginalization of black experience and history firmly established, the movie pivots into the universal. Were the vote restricted to “whites,” the country would overwhelmingly elect a man like Donald Trump to the presidency. At such a moment, art like Moonlight reminds us of the fullness and beauty of life outside the prison of identity politics.