The Mills Brothers sang about the flat foot floogie with the floy floy, and Fred Astaire danced to the song. He had a lot of latitude in interpreting it because the refrain is nonsensical: floy doy floy doy. What does that mean, and what’s a floogie, you might wonder, as I did, the song coming to mind as I watched a pair of dogs hop from foot to foot on the hot surface of a parking lot. And you might be surprised at the answer. The flat foot floogie was, in the first version of the Slim & Slam song, a floozie, altered by their record company to keep the censors off their back. But floy floy was left, and it got past the censors, who must not have recognized it as a term for venereal disease. The song, I learned, was a hit in 1938 and has been covered by a number of artists over the years. What kind of theme is that—a prostitute with the clap? And why flat feet? Then the song faded from my mind.

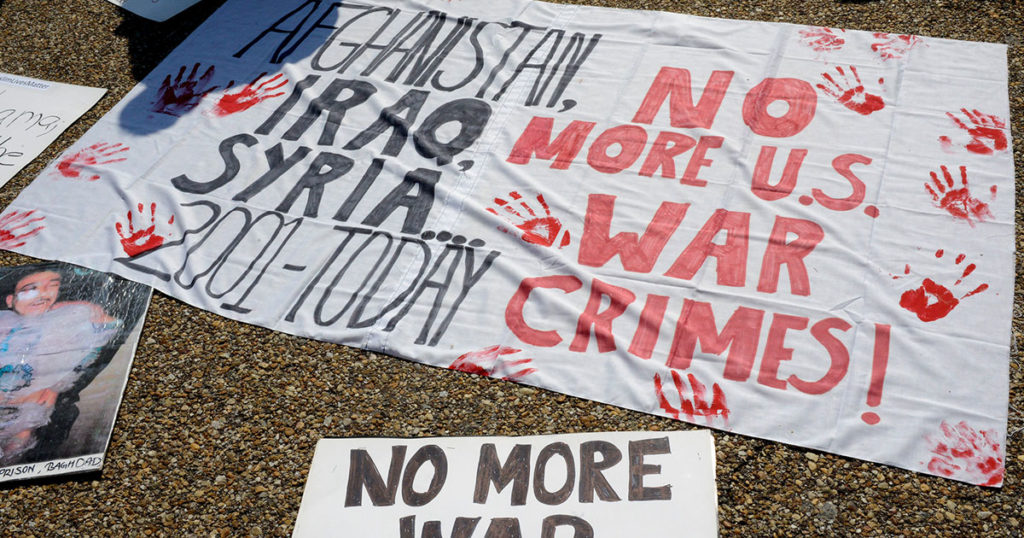

Two weeks later in Socorro, New Mexico, I stood on the town plaza with my mother and four other demonstrators. “We’re going to protest,” I had written to friends curious about how I was spending my days. This small group, which had been standing every Friday on the plaza since mid-March 2002, had first formed to protest the invasion of Afghanistan. What exactly would we be protesting now?

But protest was the wrong word. These people gather in support of peace. They stand for 45 minutes on the corner facing the post office and hold signs with slogans like Bring our troops home and Who benefits? Who pays? and Honk if you love peace. Then they pack their signs back into their cars and go about their quiet, mostly peaceful lives. But skirmishes occur in the lives of even the most pacific of people. That day, two people approached to speak to us, both young men. The first stepped across the street and onto the curb, removed his dark shades, crossed his arms, and after greeting the group at large, addressed one of the men in particular. “You gave a talk to my high school class,” he said, naming a year, and the man agreed that was quite possible. The conversation continued, and the young man said the group had stood on the corner for as long as he could remember. How old are you, we asked, and from his answer calculated he’d been 10 when the peace vigil had begun. A few minutes later, the young man said good-bye and left. He didn’t really share our convictions, he had said, but that didn’t keep any of us from enjoying the exchange. We can have our distinct opinions and still be very pleasant.

The second young man who stepped onto the sidewalk five minutes later put in doubt that proposition. He had some questions for the group, he said, addressing us quietly and with deliberation, turning slowly as he spoke, like a spotlight, to include all of us. He held his hands together and entwined his fingers, suggesting to me a young lawyer, stepping up to question a witness.

He wanted to know what we were protesting and asked who the spokesperson was. We’re just a group of like-minded people gathering in support of peace, no leader per se, someone explained, but one member of the group, the founder, was the quickest to give an answer and provided the best ones. “You’re against war,” the interrogator said, as if pondering the significance. How, he asked, would we like it if there’d been no American Revolution and we had to live under British rule? The leader pointed out that although war had been the route to an end, that did not mean war was the only way to get there. What about Hitler then, the interrogator asked, and our leader said Hitler arose from the ashes of war. And on they went, others of our group putting in a word here and there. The talk skipped from one question and reply to another, from Canada’s independence to slavery to Native Americans to racism. Our leader stated that Blacks lived in fear for their lives.

“Do you speak for Black people?” the interrogator challenged. He seemed to think he had the advantage.

“Black Lives Matter didn’t grow out of nothing.”

The young man admitted mistakes had been made.

Mistakes? The murder of George Floyd a mistake? All six of us squarely faced him.

“Error,” he said in the next sentence. “Murder,” we countered, collectively growing excited. Mistake, error—what would be the next stop on his slow retreat? Bad judgment? Yes, we would have said, bad judgment to murder a man in front of so many witnesses.

“Wrong,” I heard the man say before he changed the line of attack. Because, peaceful or not, we were attacked by this man, and we were defending our position, ever more energetically. One of us, the other man in the group, took three steps toward the interrogator. When words failed, would it come to blows?

It did not, of course, on that hot afternoon on the plaza where a handful of aging hippies held off the frowning young interrogator. At 5:15, right on schedule, we waved to the last car passing by and lowered our signs. The young man thanked us for listening to his point of view and affirmed it was our right to express ours. Elbow bumps with the leader, and he was gone. I’d never have done what he did—spend a half hour crossing swords with six others. A brave fellow.

As we packed up, the leader of our group turned to me and asked if I knew what the new sculpture on the sidewalk was. I’d noticed the black iron railing decorated with an ornamental chili pepper and had surmised it was some sort of bike stand. Before I could suggest that, though, he’d supplied an answer: a hitching post. Yes, I was about to say, a modern one for a bike, but he stopped me again. “To hitch your wife to while you go into the bar,” he finished, with a chuckle that sounded like a challenge.

At my elbow one of the women made a disapproving sound, but the leader had turned away to make his joke to someone else. Peace, respect, tolerance, mutual consideration between races—all those ideals had been invoked during the exchanges with the two strangers, and here we were with caveman jokes. What did he think women were? Floozie was a word that came to mind, along with the like-sounding hootchie. One from the 1880s and one from 50 years later. Talk about peace and respect all you want, but listen to the words. Think about the woman with flat feet. From standing on them half the day? Apparently not, but from a high-stepping gait and a sort of slapping of feet flat on the floor, a late symptom of syphilis. That poor woman was flat on her feet and flat on her back. Sick and disparaged. Yet the tune is a lively, fun one, as the marching tunes sending soldiers off to war often were. I doubt the eager singing lasted. Bring our boys home, they used to say. And why not our girls too?