Here are some things to know about Joan Didion. She was a sorority girl twice over, in high school and in college. She could read Middle English. She could produce beef Wellington for 40. She stored her drafts in the freezer. In 1956, her senior year at Berkeley, she won a Vogue writing contest, like Jacqueline Bouvier (George Washington University ’51) and Sylvia Plath (Smith ’55) before her.

In seven years at the magazine, she rose from copywriter to associate feature editor. She produced her first big piece not to a word count or a line count but to an exact character count, because another writer flubbed the assignment, and the issue was going to press.

The topic was “Self-Respect,” and already it’s all there, the ambush humor, the well-wrought sentences of an ardent New Critic, the dry-eyed determination of a great-granddaughter of the Donner Party to get the wagon train over the mountains even if it means eating your dead. It was a big chance—understudy into star—and she knew it. Acting was her earliest ambition. The literary life was a fallback.

“I have a theatrical temperament,” she said once. “Rationality, reasonableness bewilder me.” Her most renowned pieces, like “Some Dreamers of the Golden Dream,” read like film treatments, and when she talked about her nonfiction technique, she used movie terms: flash cuts, closeups.

Her trademark dread, her coded surfaces, are also noir atmospherics, a chance to let her style out and run it a little, just because she could.

She was never a newswoman. She came out of the women’s slicks of the ’50s and ’60s—glossy 80-pound paper, perfect-bound, thrillingly heavy in the hand—where power was female, neither broads nor fragile orchids but confident pros who sat in midtown offices wearing excellent Lilly Dache hats and savaging semicolons.

For a while, Didion thought she would join their ranks, until she started crying in taxicabs, married a bluff rambunctious Time writer, John Gregory Dunne (Princeton ’54), and returned with him to California just as the West Coast was about to blow, a cultural Big One that was very good for Didion’s career and very bad for her nervous migraines.

Other bad things had already happened to Didion, and she brooded about those too. One was not getting into Stanford, which made her consider suicide by pills. Another was not making Phi Beta Kappa, though eventually she wrote for The American Scholar anyway, on abandoning dead bodies in hungry-coyote country (“The Insidious Ethic of Conscience”) and the vanishing pleasures of B movies in which creatures drag small children into ponds (“I Can’t Get That Monster Out of My Mind”).

She wrote for Life and National Review, Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post. She was 70 before she finished a nonfiction book not drawn from newsstand-magazine assignments.

She was not a traveler. In 1996, The Washington Post noted, “New York, California, Miami, Honolulu—the edge is Didion’s favorite territory. She has hardly been anywhere else.”

On assignment, she would drift, absorb, go where the pack was not. Interviews and profiles often described her as shy or, more charitably, self-contained. But Neurasthenic Didion was a brand, a show-biz character, like the Little Tramp or Lucy Ricardo.

“When I was about 25,” Didion explained, “I decided it was ridiculous for a grown woman to be shy. So I became ‘reticent.’ My whole style is rather laconic,” a quality she admired in hard-shelled straight shooters like Georgia O’Keeffe and John Wayne, the subjects of two of her best profiles. She admired people with backbone, found few, and so became an expert on the American abyss (1965–2021): vice and sin, failure and neglect, collapse and pain.

In 1967’s Summer of Love, she donned a skirt and leotard and dainty Mary Janes and went to Haight-Ashbury, watching street-theater thugs terrorize a Black man and trust-fund hippies grope for language and a five-year-old named Susan get high on LSD, after which Didion famously “drank gin-and-hot-water to blunt the pain and took Dexedrine to blunt the gin and wrote the piece.”

Fifty years later, the child on acid is still a gut-punch. “Let me tell you, it was gold,” said Didion in a 2017 documentary. “You live for moments like that, if you’re doing a piece. Good or bad.”

She warned us early on that writers are always selling someone out, then did so herself. The dissonance between the tiny dithery whispery lady in the Chanel suit and the mamba prose was too much for most of her subjects to appreciate, except in retrospect.

By the ’80s, Didion was settled in at The New York Review of Books, producing long, tightly reasoned pieces on contemporary politics; she no longer needed Weird Joan, and stepped out and away, a snakeskin change. Literary journalism was changing too. She was no longer the token girl in the treehouse amid the bloat and bleat and rabid maleness of the New Journalist crowd; she was always more akin to classic witnessers like James Agee and John Steinbeck anyway. The whirligig of time has brought in her revenges: Norman Mailer and Gay Talese and Hunter S. Thompson are far less read today than Didion, especially given her late-life revival as an icon of style, personal and literary, after two raw and stunning grief memoirs on the deaths of husband and daughter.

The Dunnes were savvy, persistent bicoastal climbers—Eastern intellectuals in Hollywood, glamorous worldlings to Manhattan literati—who churned out screenplays that mostly stayed in development hell. He was a Connecticut Irish bruiser who believed in getting mad and getting even, she a rare fifth-generation California from staid Sacramento, and their marriage meant 30 years of cross-editing and collaboration.

“I don’t lead a writer’s life,” she noted. “And I think that can be a source of suspicion and irritation to some people. I’m totally in control of this tiny, tiny world right there at the typewriter.” Her writing method was part rigorous analysis, part Ouija board. (“Something about a situation will bother me, so I will write a piece to find out what it is that bothers me.”)

She was lucky in her mentors. At Berkeley, the eminent biographer Mark Schorer led her to Henry James; when she went from the Bay Area to Vogue (“a segue profoundly unnatural,” Didion recalled), the legendary editor Allene Talmey taught her to write short, then shorter. In the New York book world, Didion and Dunne bonded with fiction editor Henry Robbins, and with Robert Silver.

Didion curated her image like an old-time studio agent. Wherever the Dunne-Didions lived—Manhattan, Brentwood, Malibu—her interiors were straight out of the Gump’s of San Francisco catalog: the floral chintz, the porcelain-elephant end tables, the all-white fantasias. Nancy Reagan despised Didion, especially after an evisceration titled “Pretty Nancy,” but their taste was identical. And though Didion craved control of the life and of the work, she was also honest about the biological undertows that find a writer who is a woman, “the irreconcilable difference of it—that sense of living one’s deepest life under water, that dark involvement with blood and birth and death.”

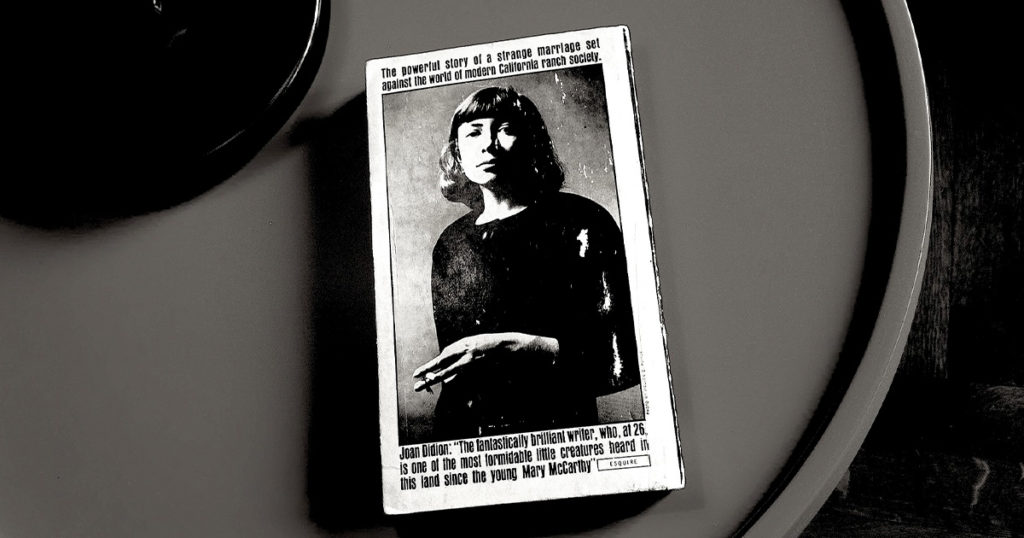

Four photos of her appear over and over: one beneath an O’Keeffe cloudscape; one beside her beloved banana-yellow Corvette Stingray; one a closeup from her 30s, lovely, wide-eyed, smoking furiously; and a defiant full-face portrait taken in 1981 in Schorer’s book-lined Berkeley office, in which she plants herself directly in front of the heaviest hitters of all: Emerson, Thoreau, Melville, Twain.

I saw that same expression in February 1989, when she accompanied her husband to Princeton for his MacLean Fellows residency. He had a marvelous time, telling war stories, dispensing slightly dated advice, explaining that writing was the manual labor of the mind. She gazed at him for 16 hours straight with Nancy-like adoration. She only broke character once, when she saw the office of Princeton’s senior Americanist. Mullioned windows framed a view of ancient elms and faux-Gothic chapel, and 2,000 books lined the walls, the precise mix of editions and scholarly studies gracing Schorer’s sanctum too, passports to a life of quiet privilege, plain living, high thinking. Born too soon, her face said, and: This nearly was mine; one flash of yearning, one of rage, both efficiently controlled.

Didion might well have made an academic. But the profession of literature, in her salad days, was as segregated as the South. Berkeley’s English department tenured only one woman, ever, before 1963. The faculty advisers who told Didion she had great talent as a critic meant she might complete the master’s and then edit a journal, or perhaps teach high school. Didion took the best available off-ramp, but in that serene office it was easy to imagine her explicating James and Conrad and also Willa Cather, another enchantress of style trained in magazines and burning with stories from flat-horizon country beyond the Missouri.

In 2011’s Where I Was From, Didion says she liked to look at a photograph taken around 1905 of a woman standing on a rock in the Sierra Nevada because it reminded her of all the durable women among her pioneering forebears.

“Actually it is not a rock,” she notes, “but a granite promontory; an igneous outcropping. I use words like ‘igneous’ and ‘outcropping’ because my grandfather, one of whose mining camps can be seen in the background of this photograph, taught me to use them. He also taught me to distinguish gold-bearing ores from the glittering but worthless serpentine I preferred as a child, an education to no point, since by that time gold was no more worth mining than serpentine and the distinction academic, or possibly wishful.”

She was raised in earthquake country, and loved a good one. A quake is the perfect excuse for losing control, especially if you have a sensibility like a seismograph. Born among the treacherous sediments of Sacramento’s river valleys, Didion will be laid to rest in Manhattan’s Saint John the Divine, its vault of ashes lying atop the city’s largest active seismic zone, the 125th Street fault. Geologists say it is 138 years overdue for a serious fracture. At least.