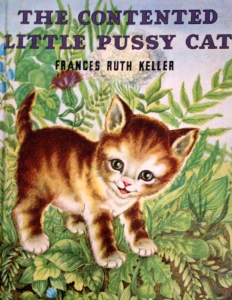

Frances Ruth Keller’s The Contented Little Pussy Cat

A book that respects the intelligence of children

I was born into a houseful of cats, 13 of them at one point—my brother came later. Cats and kittens shared my crib, my sandbox (with interesting results), and the couch. It may not be surprising, then, that one of my favorite books from early childhood was The Contented Little Pussy Cat (1949) by Frances Ruth Keller, with marvelous illustrations by Adele Werber and Doris Laslo.

I was born into a houseful of cats, 13 of them at one point—my brother came later. Cats and kittens shared my crib, my sandbox (with interesting results), and the couch. It may not be surprising, then, that one of my favorite books from early childhood was The Contented Little Pussy Cat (1949) by Frances Ruth Keller, with marvelous illustrations by Adele Werber and Doris Laslo.

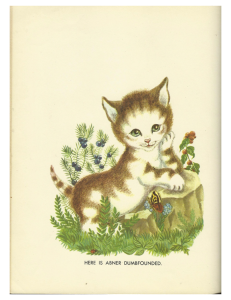

The story is still disarming: Abner the kitten impresses the other animals with his cheerfulness, and one by one, from the bunnies to Mr. Wise Owl, they come to ask him what makes him so contented. Abner thinks it over, and each time his tail “goes this way, and that way, and this way and that way,” the rhythm of the words partnered by pictures of his kitten tail in motion. All in all, the Contented Little Pussy Cat is dumbfounded by all the attention he receives for something as natural as his contentment. “Dumbfounded” was a magical word to hear and eventually to read on my own, and once again a picture draws out the joy of the moment.

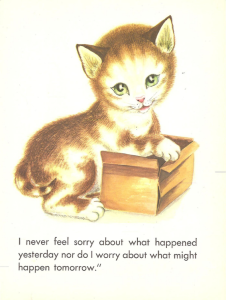

Having thought things over, Abner finally tells the other animals what he thinks must be the secret of his contentment: he “doesn’t dwell too hard on the past or worry too much about the future.”

It all seems too simple to convince the animals, or perhaps it is too hard to carry out:

And they all looked at Abner again. “Why, no good thing was ever learned without practicing,” meowed the little cat with inspiration.

And with that insight, like any good kitten, he nods off to sleep.

The repeating story, the rhythm of the language, magical words like “dumbfounded,” “inspiration,” “dwell,” “practicing”; and the little book’s message (one I still struggle to master), along with the delightful pictures, meant that I could ask to have it read every night, and eventually read it myself, getting help with “dumbfounded” at least once that I remember. I greatly miss the simple sincerity of that era, with its respect for, and challenges to, the intelligence of children. It was with abject horror that I confronted the story we were offered on the first day of first grade, which I quote from indelible outraged memory. It was the fall of 1959:

“Look, look” “Oh, oh, oh!” “Look, look, oh, look look!”

I had entered, against my will, into the dumbed-down world of Dick, Jane, and baby Sally, the toddler whose adventures with a puddle are detailed in the so-called “story” just cited. All of Abner’s intelligent philosophy went out the window; I was incandescent. The only redeeming feature of those readers, at least to my mind, was Puff the cat, as in “See Puff play.” How much more educational it would have been for all of us to “See Puff dumbfounded.”