Frightfully Askew

What asymmetry in art can tell us about the way we view sickness and health, life and death

My father’s generation endured worldwide depression and war, one catastrophe after another, and in consistently predicting further disaster, he attempted to toughen my tender skin in anticipation. But I was young, my new president was boyishly handsome and funny, and violence and privation were invisibly elsewhere—things I had only read about. Sitting in an eighth-grade class one day, I heard the announcement over the loudspeaker that the president had been shot. I assumed he would recover: there’s no way, thought I, that Lyndon Baines Johnson would be president. History wasn’t that arbitrary and capricious.

By the time I was in high school (and of draft age), LBJ had gotten us waist-deep in the Big Muddy, and the damn fool was pushing on. To blow off the steam of dread, I would make little heads of LBJ in oil-based clay—caricatures, really, with big ears and droopy nose—then throw them against the wall as hard as I could. The crushed, lopsided faces gave me some satisfaction, but the voodoo never kicked in, and the escalation continued. In retrospect, I would understand his accomplishments, such as the Voting Rights Act, but Vietnam remained his Achilles heel, a fatal flaw that outraged and frightened me for almost a decade.

But was throwing LBJ against a wall really so juvenile? I wasn’t making art, certainly, or a public protest, and have never been much of a magical thinker, but the motivation was genuine. Venting spleen, yes, but I was also sharing in an ancient practice, projecting power into an object or mask, distorting it to drive away evil spirits.

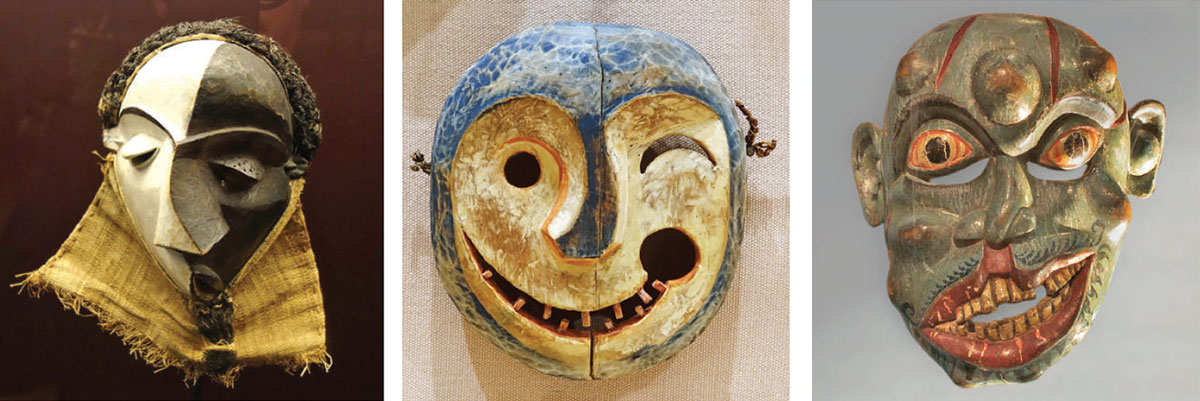

The violently cathartic act of hurling a clay head can find more solid and durable expression when translated to the medium of carved wood. The Congolese Pende people are noted for their mbangu, or sickness, masks, where the side often characterized by a skewed, sharp-toothed mouth is painted black and thought to stand for illness, whether physical or mental, while the other is white, representing spirits of the dead as agents of cure. (Sickness, having been brought on by an offense to the ancestors, needs public expiation; dancing with such masks reminds the group of the need for responsible behavior.) Although distortion is used in general to denote illness, it can specifically address the literal ramifications of facial paralysis. When a highly respected Pende hunter suffered paralysis of the face—supposedly caused by sorcery—the mask was worn as a cure. A mask from Sri Lanka represents Kora Sanniya, the demon thought to cause lameness and facial paralysis—the smile is far from happy, with no demarcation between sickness and health: the entire mask personifies malefaction. It’s harder to generalize about the marvelous Inuit masks that vary from area to area depending on significance and use, but of all the world’s representations of the human head, they seem most willing, even eager, to employ asymmetrical distortion.

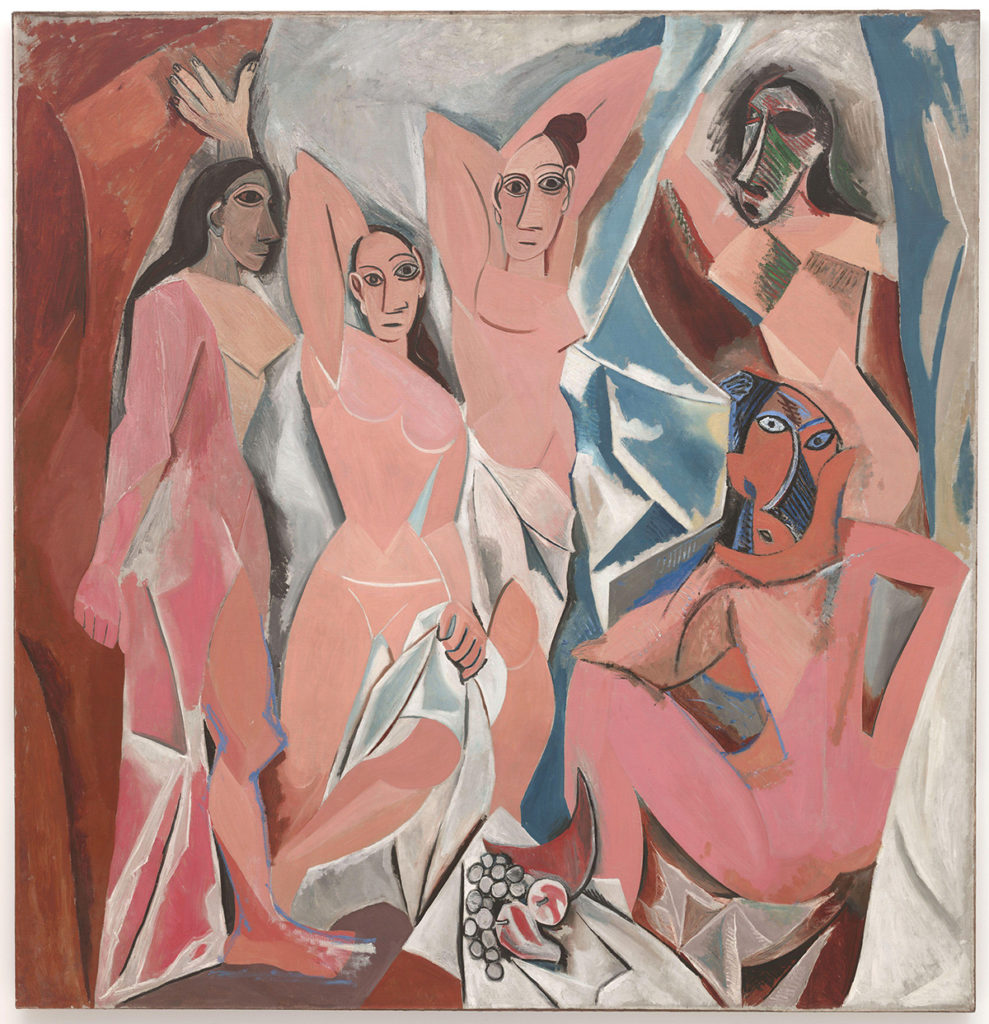

Masks have always had a rich role, from ancient Greece to Japanese kabuki, from commedia dell’arte to Micronesia. Function varies widely, but the urge to transfer or hide our identity, to alter our face to the world, seems global. Artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who visited the Musée du Trocadéro in Paris—the city’s first anthropological museum—recognized this impulse. For the young Picasso, already predisposed to see art as power over the “unknown hostile forces that [surround] us,” the museum was a revelation. His 1907 Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, depicting five nude prostitutes, appropriates the magical juju of the ethnographic exhibits. The figure on the lower right even skews her eyes as dramatically, and as asymmetrically, as a Pende or Inuit mask. This was so upsetting that some viewers considered the artist mad or ill, and one critic complained, “He has painted, or rather daubed, five women who are, if the truth be told, all hacked up, and yet their limbs somehow manage to hold together. They have, moreover, piggish faces with eyes wandering negligently above their ears.”

From left to right: a Pende sickness mask, an Inuit mask, and a Sri Lankan mask showing Kora Sanniya (Daderot/Mike Peel/Wikimedia Commons)

There’s something about asymmetry that we find deeply disturbing. Until the 20th century, world art contained very little facial or bodily asymmetry. In a continent known for a wonderful freedom to distort and stylize the human form, only Pende mbangu masks employ asymmetry—elsewhere in Africa (and the world), bilateral symmetry prevails. We aren’t alone in the animal kingdom, for almost all females seek out the most symmetrical mate to father their young. Birds definitely do it, bees do it, even educated fleas do it.

Less than a decade after Picasso painted (and only much later showed) his distorted ladies of the night, men began walking the streets of Paris who had been transformed by the ghastly weaponry of the Great War into asymmetrical monsters. Surgeons learned how to reconfigure damaged flesh, inventing the art of facial reconstruction. (To cover some of the less reparable damage, doctors created masks with the help of sculptors—for example, in the case of wounded soldiers whose skulls had been largely destroyed.) Dubbed plastic surgery, the new procedures were meant to restore the reassuring symmetry we subliminally crave. It’s as if civilization before the cataclysmic war had itself existed in a state of symmetry: unjust and imbalanced in terms of wealth and power, but very reassuring to the eye. But all those walking wounded, whom the French termed mutilés de guerre, became daily reminders that the world had gone off the rails, entering a new era of technological mutilation and distortion. Mbangu masks had come to life, and just as those Pende masks weren’t made as “art,” there was no way to aestheticize these wounded men, to relegate them to the reassuring ghetto of art.

Humans are excellent at forgetting, at denial. Europe was haunted by Verdun and Ypres for a generation but managed to all but forget the influenza that soon thereafter killed between 50 million and 100 million worldwide. Something similar happens in art. Picasso was prescient in anticipating the shape, or distortion, of his century, though arguably in his later work, the initial shock he discovered in asymmetry had lost its jolt, becoming almost a habit, less an emotional life experience than a mannerism. His Demoiselles was meant to convey the association of prostitution with the ravages of syphilis. But revelations and expressions of deep emotion often devolve into schtick. The Russian-French painter Chaïm Soutine escaped the trend toward formalism by making the melting symmetry of his portraits embody aspects of his sitters’ personalities. He thereby influenced Willem de Kooning, who sustained the initial surprises of abstract expressionism by applying them to the human form. Nonfigurative art thrived for a relatively short time before becoming conventionalized, but de Kooning made us compare our own bodies to the ones he manipulated, packing a punch. Francis Bacon seemed to tap into the existential dread of Hiroshima’s melted humans, but over time, he too succumbed to self-imitation, almost self-parody, a development full-blown in, say, George Condo, whose current work celebrates the metaphors of modernism as exhausted and empty husks. A perfect fit for today’s art world, his canny references to cubism devolve into supersize commercial performances. Gone is the horror implicit in those tragically wounded Frenchmen, with the outrage explicit in Picasso’s cartoon etching of Generalissimo Franco (The Dream and Lie of Franco, a precursor to Guernica) all but dead.

Since my days of throwing LBJ against the wall, I have found myself struggling to access the power of asymmetry in my own painting and sculpture. My limitations make most attempts look like poor man’s Picasso, a self-consciousness preempting the kind of mad spontaneity of a Soutine or a de Kooning. I admire Frank Auerbach’s midcareer charcoal heads, where distortions are convincingly found through careful, obsessively repetitive observation, but again, he seems to be looking over my shoulder when I work in his direction. This is the difference between finding and making, between perceptual and conceptual image making. A painter friend attributes this to my neoclassical temperament, about as hard to escape as it is for a lady bluebird to go for the guy with the lopsided tailfeathers.

One dictionary defines distorted as “badly or imperfectly formed,” as in “surgery to correct a distorted foot,” though synonyms for deform are more compelling to the artist, suggesting ways to energize space: warp, wrench, twist. Deformed is offensive when applied to humans, but in art, substituting “otherwise formed” resembles the goal of modernism itself: to shake us from sleep so as to truly examine the conventional assumptions about our lives. As Picasso said, “Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.”

A wax sculpture by Giambologna (1529–1608), a sketch for what would be a more finished female nude (Lincoln Perry)

Distortion seems easier to employ than asymmetry. When the sculptors Giambologna, in the 16th century, and Emilio Greco, in the 20th, wrenched, twisted, and elongated their figures, they did not make use of the kind of asymmetry found in the Pende and Inuit masks. In the West before 1900, it may be only El Greco and, on occasion, Ingres and Cézanne who did so. As a young artist, Ingres was mocked for elongating women’s arms, necks, and spines in such works as his also subtly skew-eyed Madame de Senonnes from around 1815, but the cubists loved him for taking these structural liberties—and they loved Cézanne, too, for works like Man with Crossed Arms from about 1899. Such decisions were in service of pictorial needs, not those of subject matter, and though in the work of their successors the asymmetrical eyes in Ingres and Cézanne become less perceptual than intentionally expressive, these artists were seen to be wielding a powerful aesthetic tool. The edge on that tool has dulled over time, though when Picassos were shown in Moscow in 1956, people were reportedly left depressed and exhausted—even suffering headaches—at the sight of the shattered human forms. Perhaps those viewers had existed in an aesthetic bubble, having much in common with those first entering Picasso’s studio to see the freshly painted Demoiselles. One can imagine what viewers thought on seeing Soutine or de Kooning for the first time.

The thesaurus, hard on distortion, actually goes easier on asymmetry: imbalance, crookedness, lopsidedness, and unevenness, but asymmetrical shapes can still give us the creeps, grist for the mill of horror movies. Letting go of that pesky facial symmetry has proved hard not just for academic painters and sculptors aiming to “get it right” but also for people like me hoping to discover asymmetry in nature. Still, we acclimatize to those Pende and Inuit masks, draining them of their potency by aestheticizing them. My father told me about rubber faux wounds attached to the abdomen and used to acculturate military personnel to intestinal gore. Exposed often enough, we can learn to accommodate almost anything, from Les Demoiselles d’Avignon to mutilés de guerre, less out of heartlessness than in self-defense.

Cézanne’s Man with Crossed Arms: an expressive, asymmetrical face (Wikimedia Commons)

The naïve boy in eighth grade was wrong; John F. Kennedy did die. Great expectations were killed that day, and a grisly education in disillusionment began. Presumably we keep going at least partly by looking the other way. People are dying, at times right in front of us, but we seem to live by the old adage “out of sight, out of mind.” Polar caps are melting fast, but not in our back yard. There is a grotesque asymmetry between the world’s poor and the wealthy one percent; that you are able to read this essay, however, implies you are getting by. Is there any analogy between the fierce asymmetries of much 20th-century art and the horror of mechanized death? Is our tacit embrace of one related to our acceptance of the other? By the time Kennedy was killed, I had hidden under my school desk countless times without any true comprehension of the reality of nuclear incineration. Art can try to shake us by the lapels—“Wake up!” it screams—but our default position seems to be petulant compliance. Letting the eyes on a portrait shift won’t wake us from our slumber, but it continues to subtly remind me that we can make small choices in the world, even if that world is just our studio.

My father found little comfort in the arts, which he dismissed as “bullshit,” a view related to that of my wife’s father, who summarized our species as follows: “People are shit.” Both men had been put through a wringer I’ve been spared, and when I do find counterarguments to my elders’ opinions, they usually lie in the vast corpus of world art, my consolation prize. True, we are adept at masking the grim reality my father continually warned us about. Having survived the influenza of 1918–19, he would not have been the least surprised by Covid-19, a virus that also has us covering our faces. As with those asymmetrical masks we’ve seen, if they are askew, we face the reality of illness and death. Mbangu sickness masks resemble our little protective white cloth rectangles, providing ways not just to hide from precarious existence but also to confront and be shielded from the world’s ills.