The Nineties: A Book by Chuck Klosterman; Penguin Press, 384 pp., $28

At a glance, nothing much happened in the ’90s, and even when it did, there were few repercussions. Sandwiched between the collapse of the Soviet Union and the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the intervening decade—give or take a year or two on either side—seemed like a time when America took a breath, brushed itself off, and went back to the refrigerator for another beer.

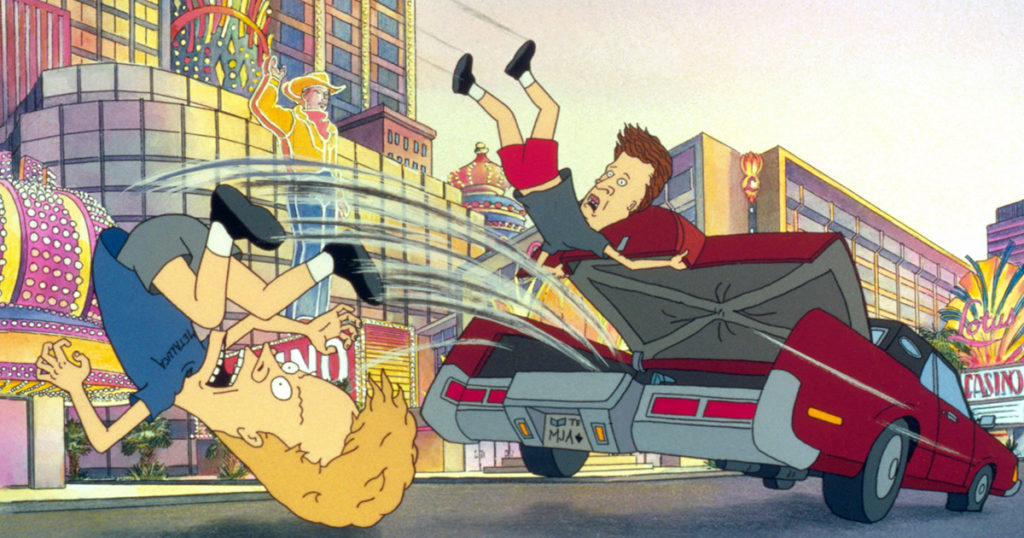

Chuck Klosterman doesn’t buy that version. In The Nineties, he makes a sustained and often persuasive case that a lot was going on, that a lot of what happened had consequences that we still struggle to comprehend, and that many of those Gen X slackers who trashed overt ambition were more like Bezos than Beavis and Butt-Head.

Klosterman points out in his introduction that many histories of particular decades begin with contrarian disclaimers: the ’70s weren’t forgettable, the ’50s weren’t dull. “There’s always a disconnect between the world we seem to remember and the world that actually was,” he writes. “What’s complicated about the 1990s is that the central illusion is memory itself.”

This is the first of several bold statements that left me scratching my head. He never fully explains what he means—that memory is flawed, or too subjective, or altogether an illusion? Or that what we thought was happening was only part of the picture and not the part that really mattered? Or is it the Mandela Effect—the phenomenon, he explains, wherein large parts of the population misremember an event in precisely the same way, an “effect” inspired by the widespread but false belief that Nelson Mandela died in the ’80s, when in fact he died in 2013.

More often than not, I questioned many of Klosterman’s takes on things, both small and large—e.g., the present and the past were not “starting to unhook” after Mike Tyson bit off part of Evander Holyfield’s right ear in a 1997 boxing match; and the TV show Frasier was not an “unabashedly highbrow” comedy “obsessed with intellectual sophistication” but a show that mocked the very idea of intellectual sophistication. Still, that doesn’t mean that his assertions, right or wrong, are ever boring.

Making my way through his dissections of Generation X, grunge, the first Gulf War, Ross Perot, the information superhighway, the Unabomber, Tarantino movies, and on and on until the disputed 2000 presidential election, I was sometimes weary but never disengaged. By the end, I had dog-eared about every third page.

Was, as Klosterman declares, the Nirvana album Nevermind “the inflection point where one style of Western culture ends and another begins, mostly for reasons only vaguely related to music”? For the 10 million people who bought copies, quite possibly. For the rest of us, maybe not so much. But I’m glad Klosterman, who speaks throughout from his perspective as a member of Generation X, has argued this point because it reminds me, very much a Boomer, how much time I spent wandering through the ’90s feeling like I had stumbled into someone else’s narrative—getting the slang wrong, missing the cool cultural references, wondering what the hell people heard in grunge, which Klosterman calls “an ironic mode of expression, performed by unironic people.” By reigniting the perpetual sense of confusion that dogged me throughout the decade, Klosterman does a truly swell job of re-creating my ’90s for me.

“The compulsion to reconsider the past through the ideals and beliefs of the present is constant and overwhelming,” Klosterman writes. “It allows for a sense of moral clarity and feels more enlightened. But it’s actually just easier than trying to understand how things felt when they originally occurred.” The particular inspiration for this observation is the 1991 Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings, but it applies across multiple topics and time zones. For the Thomas hearings, surely, but also for The X-Files, Zima, Y2K, and most especially the presidency of Bill Clinton. As Klosterman writes: “How could a married forty-nine-year-old ‘liberal’ president (a) chronically seduce an unpaid subordinate less than half his age, (b) receive unreciprocal oral sex inside the Oval Office, (c) get caught, (d) lie about it, (e) never directly apologize to the involved woman, and (f) still experience his highest presidential approval rating immediately after being impeached for lying under oath about the nature of that sexual relationship?” It is not the through line but the disconnects between then and now, Klosterman correctly asserts, that tell us the most about who we are and how we got here.

Klosterman has been labeled a cultural critic, but given the nimble speed and intellectual dazzle with which he skips from topic to topic, he more often resembles a standup comic riffing on the news, even though his goal is not to be funny, at least not all the time, and the news he’s riffing on is 30 years old.

Lurking in this characterization is the implicit acknowledgment that there is something a little shallow about Klosterman’s critique, and to be sure, there were times when I wished that he would slow down and dig deeper. Then, too, there were plenty of moments when I caught myself regarding particular passages with nothing but admiration. I have, for example, never read a more succinct description of cable news than his:

What Fox realized on election night in 2000 (when its ratings spiked upward) and MSNBC came to accept a few years later was something increasingly visible throughout the nineties, but too journalistically depressing to openly embrace: People watch cable news as a form of entertainment, and they don’t want to learn anything that contradicts what they

already believe. What they want is information that confirms their preexisting biases, falsely presented through the structure of traditional broadcasting. It had to look like objective journalism, but only if the volume was muted. Moreover, the bias expressed cannot be subtle or unpredictable; partisan audiences want to know what they’re getting before they actually get it. Unless cataclysmic events are actively breaking, the purpose of cable news is emotional reassurance.

Occasionally, I got the feeling Klosterman was coasting, just filling in the blanks (Garth Brooks phenomenon, check; Bush-Gore 2000 draw, check), but more often than not The Nineties reads like the work of a man who sincerely wants to wrestle a decade of history into focus, perhaps more sincerely than we might expect a child of the ’90s—schooled on the ethos that overt passion and ambition are so uncool—to ever admit. How times do change.