Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut by Nicholas Schmidle; Henry Holt, 333 pp., $29.99

On its surface, Test Gods tells the story of Mark Stucky, the lead test pilot for Virgin Galactic, a space tourism startup in Mojave, California, as he flies the company’s experimental space plane to the “edge of space,” 62 miles above the surface of Earth, to become one of the rare non-NASA pilots to earn astronaut wings. The book also charts the birth and ascendancy of private space travel and the brilliant if wacky characters devoted to transforming a concept from science fiction into a commercial reality.

At its center, however, it is a story of fathers and sons—and this emotional core ought to grab readers who might not care about rocket propellant or lifting surfaces or horizontal stabilizers. Of course Stucky became a military pilot: his father was a conscientious objector in World War II, and he reacted against this tradition. Of course author Nicholas Schmidle became a New Yorker writer who chose to cover wars rather than fight in them: his father was a legendary combat pilot who kept his family in the dark about his work. “Through Stucky …” Schmidle explains, “I could rummage vicariously into my father’s inner life, to try to learn something about him, to try to figure out what it was that made him do what he did.”

As portrayed by Schmidle, Stucky is a likeable, standup guy—a guy for whom the reader can cheer. He is addicted to danger, but not more than any other test pilot, a profession for which risk is “marbled into life, like sirloin fat.” The pilots even court risk in their off hours. Stucky, like many other pilots in Mojave, is passionate about paragliding—a treacherous hobby that keeps orthopedists busy with shattered heels and broken tibia.

Although Stucky’s exploits seem daredevil, his personality is circumspect. This contrasts with the swashbuckling behavior of the ground-based enthusiasts around him. Schmidle shows us Burt Rutan, the blustering visionary who founded Scaled Composites, an experimental aircraft company, and designed SpaceShipOne, the rocket-powered space plane that opened a door to space tourism. In 2004, it won the XPrize, a $10 million purse for a privately funded launch vehicle that could reach the edge of space twice in two weeks.

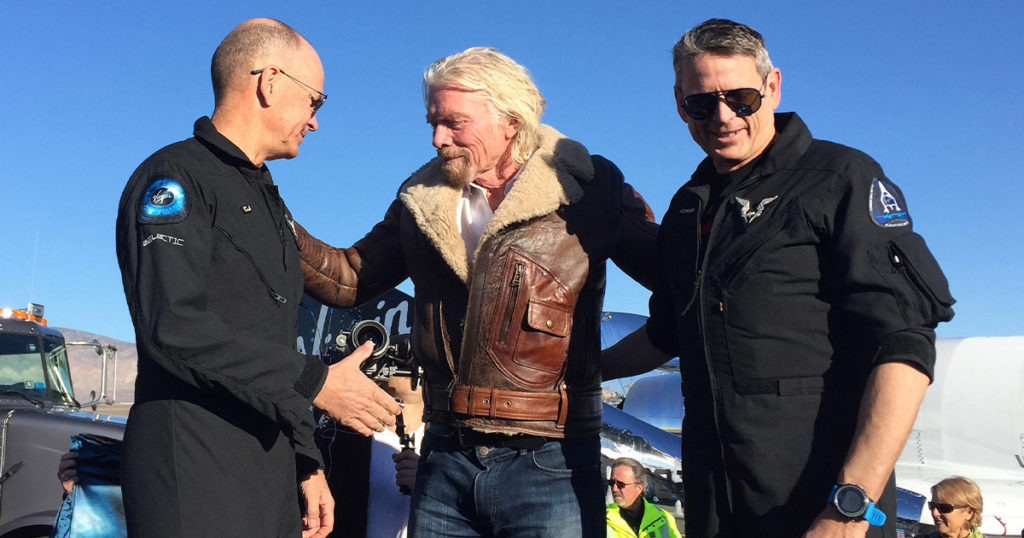

Even more colorful is Richard Branson, the British airline magnate who founded Virgin Galactic. Part charmer, part huckster, and part gimlet-eyed businessman, Branson could seemingly sell anything—including $250,000 tickets for a suborbital ride on SpaceShipTwo, the unproven successor to Rutan’s winner. Branson’s “magic,” Schmidle writes, after the company has failed to meet yet another deadline, has been “convincing six hundred people who had given him roughly a quarter million dollars ten years ago not to ask for their money back.”

And though this might seem clichéd, the book’s other important character—the character whose presence heightens the intensity of every scene—is Death. Death flirts with Stucky from the first page onward. Attempting a dive while piloting SpaceShipTwo, Stucky suddenly finds himself upside down, spinning and plummeting earthward—a situation that recalls the opening minutes of director Philip Kaufman’s adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. Yet like the Chuck Yeager character in Kaufman’s movie, Stucky doesn’t panic. He is almost “mysteriously calm. Clinical.” And he survives.

“Bravery wasn’t what set test pilots and astronauts apart from other humans as much as preparation,” Schmidle writes. But sometimes a split second can undo years of training. Death is cunning, ready to claim the best of the best—as it did in 2014 with Mike Alsbury, a pilot for whom Stucky had great respect. While flying a prototype of SpaceShipTwo, Alsbury pulled the wrong lever at the wrong time. And somewhere in the transonic zone—between Mach 0.8 and

Mach 1.2—SpaceShipTwo broke apart.

Death doesn’t confine itself to the cockpit. It affects everyone, including Stucky’s two wives and three children. His first wife could not handle its constant threat—or her husband’s protracted absences for classified work at Area 51. By contrast, his second wife, he says, has “an ‘over-inflated opinion’ of him.” But she, too, crumbled when she had to sign off on emergency protocols before an especially risky flight.

Then there are Stucky’s children. After the divorce, they sided with their mother, banishing him from their lives for years. Stucky felt the loss of Dillon, his son, most keenly. Disinvited from Dillon’s track meets, he attended nevertheless, watching from afar. With time, his daughters began to drift back to him. But Dillon remained remote. Yet in 2015, when Dillon finally reached out with a friend request on Facebook, Stucky almost rejected it. Something bugged him about

Dillon’s word choice. But to this reader’s vast relief, Stucky relented.

The reunion of father and son is an emotional climax in the book. Stucky’s professional triumphs—and, by extension, the triumphs of Virgin Galactic—are thrilling. But Test Gods is a human story. Unlike the launch vehicles developed by private rivals SpaceX and Blue Origin, SpaceShipTwo is not a robot. It is meant to be flown by people.

By male people, seemingly. Women don’t get much ink in Test Gods. Beth Moses, a former NASA engineer, has a cameo in microgravity when she flies as the first tourist on SpaceShipTwo. But I don’t get the sense that Schmidle likes either her or her husband, Mike Moses, another former NASA engineer and Virgin Galactic vice president charged with press access. After an early version of Test Gods ran in The New Yorker, Moses, who had allowed Schmidle to embed with the company, slammed the door in his face. Even before the exclusion, Schmidle painted an unflattering portrait: Beth is taller than Mike and has “shampoo-ad hair.”

With regard to the absence of women, though, I did find one seeming oversight distressing. I was in Mojave in 2004 for the first qualifying flight of SpaceShipOne. Banners everywhere announced the Ansari XPrize, not merely the XPrize. The name change was important. Peter Diamandis, who founded the prize, was not able to raise the full $10 million purse by the time the rules required. So Anousheh Ansari, a woman in the tech industry, ponied up the money. She went on to travel privately to the International Space Station, becoming the first Muslim woman—and first woman of Iranian descent—in space. I don’t think Schmidle’s story would lose momentum if she were highlighted upfront.

This is, however, a minor quibble with a gripping, comprehensive, and deeply felt book. I like Schmidle’s openness about the way his relationship with Stucky evolved: from “source” to “subject” to “friend.” And I admire the way he places himself—and his father—inside the story, rather than affecting an artificial distance. Referencing Herman Melville, Schmidle writes, “we are products of our past, entangled with kin by ‘complicated coils,’ stronger than we care to admit.” Maybe stronger even than the surly bonds of Earth.