From Murderpan to Mattapan

A writer’s traumatic experiences lead him to travel in time to the places where he was hurt

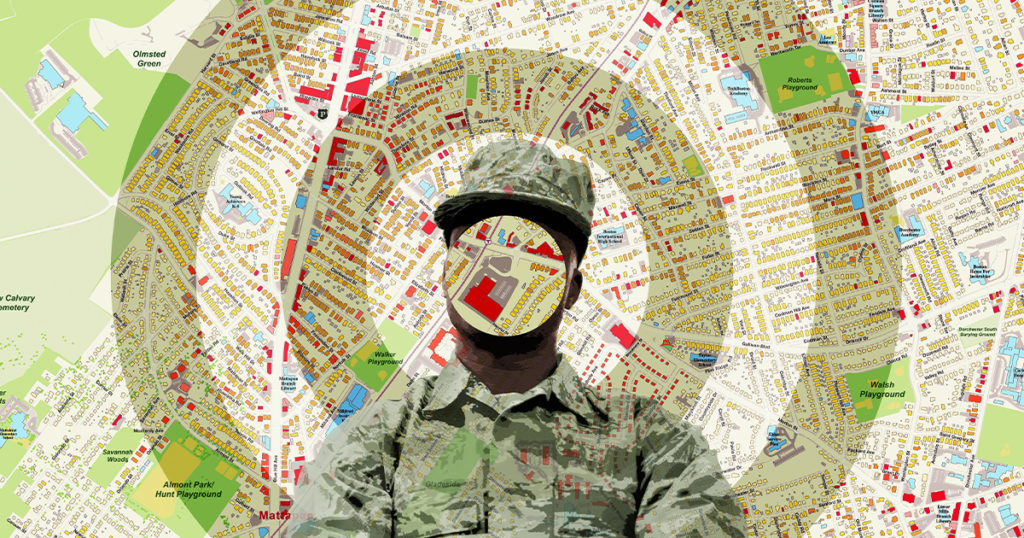

As a child, I imagined I would escape Boston’s Mattapan neighborhood through my writing. As an adult, the Mattapan branch of the Boston Public Library hosted the writing classes I taught, where, among other things, I guided my adult students through the steps of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. In it, he introduces his idea of the “monomyth,” also known as the “hero’s journey”: an outline of storytelling moments that run through many of the heroic myths told around the world and that shape a preponderance of contemporary stories. Campbell called his work a pursuit of “human mutual understanding” through “myths and folktales from every corner,” quoting the insight of Hinduism’s Vedas to underscore his intent: “Truth is one, the sages speak of it by many names.” Perhaps there are Hindu myths that symmetrically complement the myths of Mattapan, now my place of business, mythologized as murderpan for as long as I’ve known it.

Of all the murdered people I cross paths with, one rendezvous is most common, snatching me out of the present the way time eventually snatches away everything. To be fair, time does seem to give as well. Frequently, it lets me borrow my round, prepubescent body and my grandmother’s couch. I am sitting on a soft cushion on a Saturday afternoon. My age is hidden from me, but I am young enough to feel cool because I am hanging out with a big kid, a 15-year-old. I know his age because I ask him. He’s a friend of my cousin’s, and this is the only time we meet. Unlike other big kids, he doesn’t tease me. He just asks for my name, and we quietly watch college football.

The next day, my father tells me that the boy I was watching football with is dead. He’s been shot on his porch. His father held him while he died.

I tell myself that this incident hijacks me so often because it is being kind, because even time doesn’t always want to be cold and mathematical. That’s why the incident hides my age. It refuses to tell me whether I am nine or 10 or 11 years old because numbers alone can’t truly express an age. This slice of time tells me only that my grandmother’s cushions were soft and so was I. That I was, once, a person who shared a Saturday afternoon with a stranger and was comforted. This slice of time reminds me that my past can become my present because the difference between the two is a myth, that if I can be comforted in the past, then I can be comforted in the present.

The trickiest part of discussing time travel is resisting the urge to convince people that you aren’t insane. For me, the weight of that trickiness lies in the twin realities that time travel may be powered by post-traumatic stress disorder and the human tendency to fail at distinguishing PTSD from madness. But I don’t worry too much about it, for neither an elegant argument in defense of my sanity nor a capitulation to the idea that I am a lunatic will have any bearing on my experience of time travel.

The second-trickiest part of discussing time travel is that the explanation that supports time travel and the one that frames time travel as psychosis are identical: it’s all in your head. Maybe Sherlock Holmes summed up humanity perfectly when he said, “I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.” Or maybe Holmes only summed up why humanity can’t be summed up. American scientist Emerson Pugh once said, “If the human brain were so simple that we could understand it, we would be so simple that we couldn’t.”

The third-trickiest part of discussing time travel is that sometimes time travel is a hijacking. Humanity’s lizard brain—first described in the 1960s by neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean, who hypothesized that the lizard brain, which he called the “R-complex,” was the source of primitive survival instincts—has, as recently as 2020, been discredited as lacking any true “foundation in evolutionary biology.” But the idea, as a tool for understanding fear, still lingers with me, the lizard brain as the source of strange behavior that leaves one feeling alienated from one’s self. The idea, as my therapist explained, holds that deep and slow breaths trick the lizard brain into believing there is no reason to run. I sometimes ponder the image of a tiny lizard, curled into a ball and nestled inside my skull, and liken its activity to hogtieing a prisoner in a time machine’s back seat, as that’s essentially what happened to me despite my body’s remaining confined within the walls of the Mattapan branch of the Boston Public Library.

I’ve been asked only once how time travel feels, an important question that I cannot answer but do appreciate. Considering the question helped me realize that even feeling is a matter of time. Nerve endings need split seconds. The soul may need years. And time may be inclined to provide neither. But my best approximation is that time travel feels like holding nothing in your hand while lingering with the possibility that even nothing is something.

The next most frequent rendezvous I have with a murdered person is with a woman I never met. We grew up on the same long street in Mattapan and had mutual friends. One Friday night when I was in my mid-20s, I dreamed about a horrific fight happening in front of my friend’s house, only a few doors down from where I used to live. A dozen of us brawled in the street, infected with madness. The next day, a drive-by shooting occurred at that exact location. I called my friend as soon as I heard, and he told me what it felt like to come home from work and find his fence covered in blood. He told me about the woman, about how she had moved out of the neighborhood and was only there that day to pick up a friend.

There’s an absence of logic in this reality. In my dream. In the woman’s dying in a place that she had left behind. In her becoming someone I now meet all the time, even though I never met her when she was alive. But there’s something logical about that absence.

I’ve even wondered whether the absence of logic is the point. I’ve imagined America’s Federal Housing Administration of yesteryear delineating its redlining initiative with a wild-eyed scientist at the head of a boardroom. “We herd them here, here, and here,” the scientist says. He slaps a different spot on the map for each here. “We fill these places with insanity. And we watch the many ways that insanity can manifest. As it is in Tuskegee, where we watch the many ways that syphilis can manifest.”

While describing to my students the final section of the hero’s journey, which considers a mythological hero going home after accomplishing her mission, I experienced a fleeting sense of displacement. Metaphorically, I felt the way one does when looking for house keys. Psychologically, the lizard had slipped into the time machine, fastened her seatbelt, and was warming the engine. Physically, I was still in Mattapan, teaching.

“Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest …” I was reading aloud from my notes, about the hero trying to find her way home. The words came slowly. The absence I sensed grew.

The lizard had turned on the time machine’s radio. Trap music was sliding from the speakers while she rolled a blunt. The absence that was growing was me.

“Often they must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to everyday life,” I said. “Especially if the person has been wounded or weakened by the experience.”

“This was my brother,” I continued. My body was speaking to the class now while I, leaving, became hyperaware of the past and focused on a time when I had been wounded and weakened. “He was my ‘guide’ after I got out of prison.”

I was gone, hogtied in the back seat of a time machine.

Imagine moving the tip of your tongue toward one of your teeth to find the tooth absent. Only air and soft gum tissue where you expected firm resistance. While the words about my brother escaped my mouth, nothing was where I’d left it. I could no longer smell the cheap coffee brewing in the corner of the classroom. I could no longer feel my fingertips rub against each other as I tried to smudge away marker stains. All I could smell were the leather seats from my brother’s giant white Yukon. All I could feel was the sense of smallness I had known whenever I sat in those seats, especially after prison shrank my body.

And then I returned.

I thought about how I didn’t mean to say what I’d said. None of my students appeared discomforted by my disclosure about prison. I took a slow breath, just as my therapist had taught me, and wondered why I’d said it.

“Master of the Two Worlds.” My gaze was on my laptop’s screen. “For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between …”

Perhaps time travel feels mystical because even conventional travel possesses mystical qualities. Routine travel has a starting point (my childhood home in Mattapan), a destination (the Mattapan branch of the Boston Public Library), and the traveling object (me, released by the starting point and received by the destination). Inherent in this arrangement is an unavoidable sacrifice, reflected in a quotation by science fiction author Octavia E. Butler: “All that you touch, you change. All that you change, changes you.” The starting point that once held me, and vice versa, doesn’t only release me toward a destination; it also releases itself into a nothingness that we call the past.

I eyed the white walls of the classroom. Four gray tables were pushed together to accommodate me and my students. A giant screen hung on the wall to my left, displaying text from my laptop. My color-coded notes tattooed the whiteboard behind me, comparing and contrasting the hero’s journey with the three-act story structure.

The library, like my classroom inside it, is new and beautiful. Speaking to my students in such an environment validates my sense of professionalism. But it’s also in Mattapan, and during the previous week’s class, an ambulance blared to a stop outside the window. When I asked the librarian what had happened, he shook his head and said, “You don’t want to know.” The week before that, the police were called because a group of teenagers had tried to jump another teenager for his phone.

“Master of the Two Worlds. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance between …” I was reading again, and contemplating how I had gone from being a child, surviving murderpan, to teaching writing classes in Mattapan.

“Some of the hero’s journey trials feel a lot like growing up in Mattapan,” I said.

I scanned the room again.

I didn’t understand why I’d said that.

I wanted to know when I had gone to before blurting the words. I felt fear, as if I’d just learned about a murder. But I couldn’t name which murder my fear was responding to. Time travel is rarely comprehensive. But Mattapan is as much a time as it is a Boston neighborhood.

“Damn,” a student said. Her curiosity and concern pulled me back to the present. I was failing them. “Was Mattapan really that bad?”

“It was terrible.” I hadn’t yet fully returned to the present. “I know many murder victims.”

Maybe this confession soothed my lizard brain because, suddenly, I was back. I held my breath and hoped the word murder hadn’t affected my students the way it often affects me. I hoped that I hadn’t launched any of them to some terrible point in time. And for an instant, I worried, as if I were bloodstained, as if I had brought blood back with me from the past.

I assume that it is physicality, and respect for its laws, that raises skepticism about time travel and its metaphysical movements from Point A to Point B. And I assume that my uncertainty about the relevance of physicality is why I shrug off the skepticism.

A therapist once explained to me how trauma reshapes the brain. During traumatic moments, in the interest of survival, the brain releases the stress hormone cortisol into the hippocampus, a structure deep in the temporal lobe that is essential for memory formation. But high levels of cortisol can eventually kill hippocampal cells, thereby shrinking the hippocampus and altering the brain’s shape. This suggests that you need not suffer a physical trauma to be traumatized physically. You may only need to witness a stranger’s levying a prison sentence. Or have an innate sense of history.

James Baldwin wrote that “the great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it in many ways, and history is literally present in all that we do.” Maybe that’s why time travel feels like an absence of logic. Despite Baldwin’s noting history’s literal presence, we’ve convinced ourselves that the past and the present are separate. Maybe we’ve told ourselves a story about the border between the past and the present, and though the border never existed, we believe it exists because the border is a story, not a fact.

Facts, like the fact that I spent a year in prison, and the fact that my brother picked me up from the airport after my release, and the fact that the seats in my brother’s car were massive, all engage what are called Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas of the brain—areas fundamental for language processing, for comprehending what I’m communicating when I use words like prison, airport, or seat.

But when fueled by imagination—according to several studies—the story of how my brother picked me up from the airport after I was released from prison and drove me home in his giant white Yukon becomes an immersive experience. My olfactory cortex is activated—and so the smell of my brother’s leather seats once again lives in my nostrils. My motor cortex turns on, as though I’m truly clenching my jaw and fighting back tears. My sensory cortex revs, convincing me that I am feeling the seatbelt buckle in the palm of my hand.

Whenever I return to the present, I almost always feel like I’m being reintroduced to the body. Not a reawakening, as if I’d just come out of a trance, but a recollection of all the stories the body holds, the way the body recounts its stories, and how the body is what connects us to this idea of the present. The body is why I am, instead of I was or I will be. And maybe that’s why I sometimes resent the body and am grateful that my own is not the self but something closer to the self’s territory. The present, to which the body keeps me attached, is not enough, likely because the present is so fleeting that it’s both here and gone at the same time.

Baldwin’s idea that history inhabits the body was verified, somewhat, by a study involving mice and the scent of cherry blossoms. Neuroscientists at Emory University taught male mice to fear the scent of cherry blossoms by combining the scent with mild electric shocks. Two weeks later, the mice bred pups that were raised to adulthood before smelling their first cherry blossoms. When finally they did, they displayed signs of fear and anxiety—as did their pups, two generations removed from the original test subjects. The experiment was an early step in the field of epigenetics, the study of how external factors affect the genetic inheritance of organisms. Reading about it left me wondering what stories live in my veins. An anecdote about mice that inherited fear is discomfiting. The story leaves me with unanswerable questions about identity and the borders of the self. Where do my fears begin? Where does my courage end? How much of my life, including my time travel, is the product of time’s also being a vessel, traveling through me?

I know that I joined the U.S. Army because my life felt aimless. I wanted to be a military journalist during the Iraq War, which felt like an upgrade, leaving Mattapan’s proximity to violence for the Army’s proximity to violence and a paycheck. But decades before my birth, my father also joined the U.S. Army. In light of mice fearing cherry blossoms, I now ask myself where my father ended and where I began when I made the decision to enlist. I especially ask because knowing might help me understand who else was with me during my year in a military prison.

I also joined the U.S. Army after learning that all of the journalist positions were filled. The recruiter had assured me that I would still have a military occupational specialty (MOS)—that is, a job—where writing was a priority and killing was not. And I know that this specific request for an MOS without a leading obligation to kill was because of my time traveling.

I tell people that I know six murder victims by way of my Mattapan upbringing because six is as high as I’m willing to count. And my involuntary trips to those murders became more frequent after I learned that my MOS was actually centered on killing, that I had been deceived—deceived in a way, as I learned after speaking to other soldiers with the same MOS about their experiences with recruiters, that was not uncommon. This manifest insanity even flummoxed my war veteran father—a member of an old guard, I suppose, and the era of the draft—but not the modern officers who would defy Army mores by telling me, a lowly private, stories about recruiter manipulation.

A moment I often find myself revisiting involves an exchange with my company’s colonel. After telling him about what had transpired with my recruiter, the colonel said, “You should’ve done your research.” I think ego is why I’m dragged back to that moment. I’m irked by my failure to offer the candid and timely response: “When you’re a civilian, sir, talking to a recruiter is research.”

Occasionally, time traveling, while a soldier, would result in an explosion of tears. I would experience my time travels by way of nightmares. I came to expect waking up with scratches on my face, which an Army therapist explained were of my own doing, a kind of stamp for my passport after having taken another trip.

Ultimately, I was ordered to travel to Iraq and kill people. I refused. And, unironically, history played a role in that decision. Before deciding I would not go to Iraq, I read Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, including a scene in which Douglass, then enslaved, engaged a slave master named Edward Covey in a fistfight and won. Afterward, Douglass declared that for the rest of his life, any man who intended on “whipping” him would also have to kill him, because he would fight back.

I was inspired by Douglass’s defiance and decided to replicate it. The Army lied to me and I felt no obligation to honor its mendacity. I refused to go to Iraq and was court-martialed. After my military lawyer shot down most of the charges, my potential 20-year sentence was reduced to 13 months, to be served at the medium-security prison at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. With good behavior, I was released after 10 months and five days as a kind of stranger to myself because, as Octavia E. Butler wrote, “All that you touch, you change. All that you change, changes you.”

Prison had left me dizzy despite its similarity to Mattapan. Both involved basketball games with pimps, drug dealers, and violent offenders. Both inspired notions of escape. Both, like time, have taken from me and given to me. Perhaps the dizziness came from seeing prison bars and prison guards and, after returning home, feeling like they still surrounded me, as if being imprisoned in the past, in a way, also meant being imprisoned in the present.

Not long after my release, I joined my family on a trip to Uganda to mourn the death of my mother’s brother, Uncle John. I had met Uncle John only once, and because he didn’t speak much English, we didn’t really interact. But I usually had pleasant conversations with Uncle John’s perpetually smiling son, my cousin Jackson.

“You lose weight?” Jackson had asked on the sunny day of his father’s memorial. Uncle John’s grave was no more than 20 feet from where we were sitting, the Ugandan grass staining the hind of my jeans.

Jackson and I hadn’t seen each other for almost five years. His English was still inconsistent. And I didn’t want to dive into the winding story of how I had landed in a military prison, where I bare-knuckled a heavy bag as stress relief and accidentally turned a paunch into a six-pack.

“Probably,” I said. “I was in the Army for a while.”

His eyes widened. “You what? The Army!” His smile flatlined. “Are you crazy?”

I grinned and recalled that I was in Uganda, where a word like army carried a similar definition but a very different history. “Maybe,” I said. “I … I don’t know.”

He eyed me. His smile returned. “There were some people up north. Started going from village to village. Gathering men to fight. To fight in their army.” His head tilted toward his shoulder. “My father said, ‘I’m not killing anybody for you.’ They threw him in jail.”

“What!”

For a moment, I thought Jackson was joking, that one of my parents or my brother had told him what had happened to me and he saw the opportunity for a prank. But Jackson’s smile was holding. It was the smile of childhood reminiscence, a boy time-traveling through the adventures of his recently deceased father.

“Eventually, they let him go,” he said.

I went to my mother and asked if the story about Uncle John was true. She gazed at the sky while connecting the dots. Her brother was in the ground, just a few feet away. She nodded her head and laughed. “Oh, yeah. That did happen.”

For years, I wondered why my mom had not made the connection between myself and Uncle John sooner. But time travel can be perilous. Why relive what had happened to her family in Uganda when it was happening again to her family in Boston?

I have no idea what time is and understand but little of what it does. Time is the measuring stick for existence. Time, as a word, is also a way of leveraging Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas of our brains, of processing existence through the power of language so that we’re not overwhelmed by the workings of existence. So we can say, “The movie was two hours long,” instead of, “The movie required 2,080 miles of Earth’s rotation, as the equator flies.” And time is why I can watch an exploding star, 13 million light-years away, and say, “Look at what’s happening right now and 13 million years ago.”

But time is also a building block. If time is a measuring stick for everything within the framework of existence, then time is also, to some degree, the substance of everything within the framework of existence. Albert Einstein considered time to be the fourth dimension, following the three perceptible dimensions of depth, height, and width. If one were to take the dimension of depth away from a cube, the cube would cease to exist and become a square. I think about cubes becoming squares when I ponder what happens to a person—whose body can be measured by the first three dimensions, and whose existence is measured by the fourth—when that person’s command of time is amputated, when a person’s time is confined to a prison cell. I wonder if that circumstance flattens a person, as with a cube made into a square.

A terrifying aspect of time is the intricacy of its design. We’re anchored by our bodies to the present, where the past informs our idea of self. Our present relationship to the past influences how we travel into the future. And the hope, or lack of it, that we have for the future affects what we do with our present. Such interconnectedness, where one drop of vitriol could poison all three phases of time, makes time travel a necessity.

In prison, I dwelled as much as I could in the future because the present was too flat. And because there was enough story in my past to do so. I filled notebooks with stories as a way of telling myself the history of the writer I would become in the future, in the world beyond the body, prison bars, and strip searches. I wrote stories as if I were free all along, as if I were walking through the apotheosis stage of Campbell’s hero’s journey—when the hero has discovered something divine within—because I was not built from incarcerated body parts. Because I was built from time. Because time travels through me as I travel through it.

There is an unquestionable absence of logic in this, in slipping away through time and folding my future into the hole that was punched into my present. But maybe this abandonment of logic was an appropriate response, a means of survival. Or, maybe, this abandonment of logic was a misuse of my time. I doubt I’ll ever fully know because of the inescapable paradox: if time were so simple that we could understand it, we would be so simple that we could not.